Slaughter's Hotel

Proprietor Richard Slaughter in a hotel ad at its second location (529 N. 2nd Street), appearing in New Journal and Guide, March 9, 1935.

Known Name(s)

Slaughter's Hotel

Address

529 N. 2nd St. Richmond, VA

Establishment Type(s)

Hotel

Physical Status

Demolished

Description

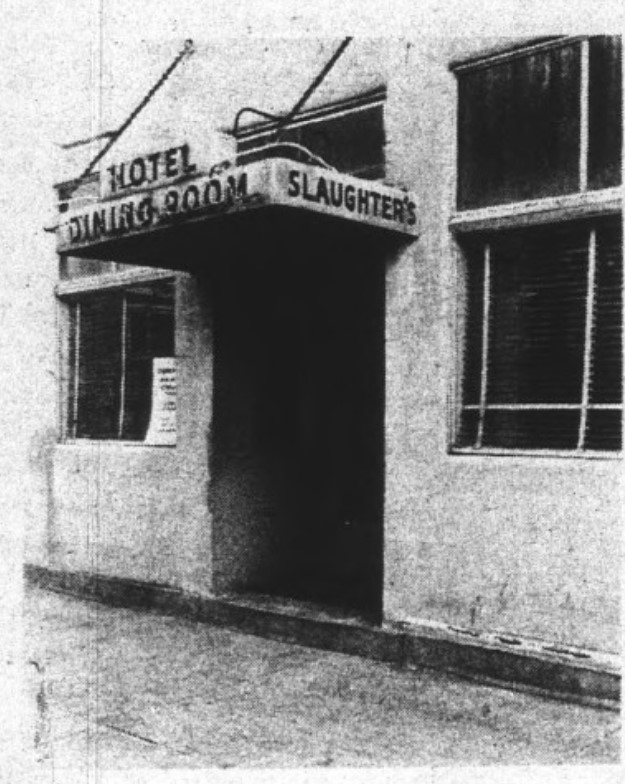

The 1952 Sanborn Map shows this building as brick, three-story, with a restaurant on the ground floor and a hotel above. The business spans both 529 and 527 N. 2nd Street, which are separated by a narrow horse alley. No. 529 N. 2nd Street is 40' wide, with a non-combustible (i.e. slate or metal) roof. A narrow, three-story frame addition separates the main block of the building from a rear one-story brick addition. The business is across from the Elks Home Capitol City Lodge and the Hippodrome Theatre, both catering to African Americans. The block that Slaughter's was located on also had two other hotels for Black travelers. A 1970s image of the entrance shows what appears to be a concrete facade and a doorway flanked by two windows. A simple concrete (?) slab canopy abovew the doorway has "HOTEL / DINING ROOM" at front and "SLAUGHTER'S" on the one visible side. The canopy is held in place by two chains anchored to the facade above.

Detailed History

(For brief context on the importance of this N. 2nd Street block to the history of Jackson Ward, a National Historic Landmark, see entry for Miller’s Hotel / Hotel Eggleston.)

African American proprietor Richard Slaughter first operated Slaughter’s Hotel at 514 N. 2nd Street in Jackson Ward (see entry). In 1931, he moved it across the street to a former bank building at 529 N. 2nd Street. This account comes from Gertrude Duncan (née Gertrude Atwell Taylor) in a 1974 article, “Slaughter’s: Black Richmond’s ‘Plymouth Rock’,” in The Richmond Mercury. Duncan, a Black woman who moved to Richmond from Red Oak, Virginia, in 1926, began working for Richard Slaughter when the hotel was located at the No. 514 location. At this time, she was unmarried and went by her maiden name of Taylor.

Given Duncan’s account, it is unclear why the Green Book editions for 1938 through 1948 list Slaughter’s old location (No. 514) before shifting to the actual location (No. 529) for the 1949 through 1967 editions. It is possible that whoever suggested the listing for inclusion in the 1938 edition confused the old with the current business, and then this incorrect information was repeated until the correction was made for the 1949 edition. Additional documentation supports the hotel’s presence at 529 N. 2nd Street well before it first appeared in the Green Book. The Richmond Directory for the years 1933 and 1938, for example, lists Richard Slaughter’s residence as his 529 N. 2nd Street hotel, where he also served as the manager; in the 1933 edition, Taylor is mentioned under the separate hotel listing at this address. A 1935 advertisement, which includes a photo of Richard Slaughter, in the New Journal and Guide refers to Slaughter’s Hotel & Dining Room at No. 529. It is described as a “New and Modern Hotel” with a dining room, open from 6:30 a.m. to 3:00 a.m., that is “A Good Place to Eat.” A private dining room was available upstairs. A similar ad also ran in the 1942 Richmond Directory.

One guest of note in this period was Richmond native Oliver Hill, who, after graduating from Howard University’s School of Law, stayed at Slaughter’s in December 1933 to take the bar exam the following morning (Hill would go on to become a leading civil rights attorney who successfully fought to bring down segregation in schools). The article (North of the James, 2003) adds that Slaughter’s was “a place famous for its Smithfield ham steaks.”

The 1940 U.S. Census references Richard Slaughter, age 60, as the hotel manager and Gertrude Taylor, age 33, as the business manager, with both living at the hotel and working 56 hours per week. Rosa Taylor, age 27, single, and possibly Gertrude’s sister or relative, also lived at the hotel and worked there 40 hours per week as a waitress. The census notes that Slaughter never had a formal education, Gertrude Taylor went through four years of college, and Rosa Taylor went through three years of college (it also indicates that Rosa was living in Akron, Ohio, in 1935).

The World War II years, based on a 1974 account from a Slaughter’s regular, was a time when this block of N. 2nd Street had three hotels and four nightclubs. The regular proclaimed, “If Second Street was where it was at in the neighborhood, then Slaughter’s was where it was at on Second Street.” He added, “Hundreds of small social events were held at the hotel, and people would pour in late at night after dances and other activities ended.”

Proprietor Richard Slaughter was born in Fluvanna County, Virginia, to William Slaughter and Louisa Scott Slaughter, both native Virginians (further research is needed to determine if they were born enslaved or free). Richard’s birth year varies, with his marriage certificate and his divorce decree indicating 1875, his World War II registration card showing March 10, 1878, and his death certificate indicating 1880. The latter document lists Goochland County as his place of birth, but Fluvanna County, appearing on his marriage and divorce documents, appears more likely. On February 18, 1904, he married Elizabeth Scott in her native Richmond. They separated two years later, in 1906. The divorce decree (February 17, 1944) lists Richard as the plaintiff; Elizabeth, age 68 and then living as a housewife in Newport News, Virginia, as the defendant; and the cause of divorce as “desertion,” with Richard being granted the divorce. By 1942, Richard was living at 1030 Wickham Street (extant) in Richmond, where he spent the rest of his life. He died at Community Hospital in Richmond on April 21, 1945, and was buried in Richmond’s Woodland Cemetery three days later.

At some point following Slaughter’s death, Gertrude Taylor bought the business and either took up residence or continued living at 1030 Wickham Street (while her relationship to Slaughter outside a professional one is unclear, she appears to have been his main point of contact). She was born in either c. 1907 (1940 U.S. Census) or January 19, 1909 (death certificate) in Red Oak, Virginia, to L. R. Taylor and Martha Taylor (née Wilson). On September 6, 1947, she married Theodore T. Duncan at a Baptist church in Richmond. The marriage certificate lists Gertrude, age 40, as a hotel operator. Theodore Duncan, age 31, is listed as an assistant manager of a hotel (presumably Slaughter’s) who was born in Crichton, Alabama. His parents were Owen J. Duncan and Fannie Duncan (née Howard).

Gertrude and Theodore Duncan were still living at 1030 Wickham Street in 1950, according to the U.S. census of that year. They lived with their adopted daughter, Elaine G. Davis, age 19; their adopted son, Rudolph Robinson, age 5; Pearl Lockley, age 26, a maid; and two roomers, Frances W. Abrams, a 35-year-old elementary schoolteacher, and Marcella H. Barnes, a 27-year-old waitress at a hotel (possibly Slaughter’s).

Slaughter’s Hotel, under Gertrude Duncan’s management, was an important hub for African American community and civil rights groups. From 1953 through 1962, the Suffolk News-Herald writes that the Board of Governors of the Negro Garden Clubs of Virginia held its meetings at the hotel. According to a 1974 account of Slaughter’s in The Richmond Mercury, the hotel hosted meetings for the NAACP, which met here to strategize how to dismantle legal segregation in Virginia; the Civic Council; and the Democratic League. The League’s successor, the Richmond Crusade of Voters, “the most potent indigenous black political organization to ever get its electoral feet wet in Richmond,” began meeting at the hotel in 1956. At the time of the 1974 article, that group and the NAACP’s local legal staff still met at Slaughter’s.

The hotel’s food kept people coming back. The Richmond Mercury account noted the Jim Crow era was a time when “black people both in Richmond and up and down the entire East Coast knew Slaughter’s as a place where the accommodations were good and the food was superb.” Dr. William S. Thornton, former president of the Richmond Crusade of Voters (not to be confused with the group’s longtime historian, William A. Thornton, who was not related), recalled, in 1974, his childhood connection to Slaughter’s: “I used to bicycle here from my home in the West End six miles away just to buy myself a club sandwich. They must have sold 150 or 200 a day here. Those were the best sandwiches in Richmond.” (It is possible that the West End home that Thornton refers to was located in Westwood, a historically Black community and the only one known to exist in the West End. Westwood is approximately six miles from Jackson Ward.)

As others in the area have said, integration and the construction of I-95, which cut Jackson Ward in two, led to the hotel’s decline. However, The Richmond Mercury’s 1974 article asserts that Slaughter’s was “a bit run-down but still clean, and black Richmonders still frequent it regularly.” This included many professionals, who ate there daily (except on Tuesdays, when the restaurant was closed), and people who packed the restaurant on Sundays after church. The article notes that Frances Calvin, the cook, and Artie Williams, the server, had been working there for 20 years. Gertrude Duncan, described as often sitting quietly at a table, recalled, “This is an old place … But a lot of wonderful things have happened here.”

Duncan died, age 67, on March 31, 1976, at Richmond Memorial Hospital. Her funeral was held at A. D. Price Jr. Funeral Home, 208 East Leigh Street (extant), and she was buried in Riverview Cemetery in Richmond. Her husband Theodore died, age 76, on January 9, 1993, at the same hospital. His funeral was held at Scott's Funeral Home in Richmond and he was cremated at Greenwood Crematory in Goochland County, Virginia. At the time of his death, his residence was still 1030 Wickham Street, where he had been living with his second wife, Ruth G. Duncan, who survived him. He was listed as "hotel owner," perhaps indicating he ran Slaughter's after Gertrude's death.

The building that housed Slaughter’s, along with several other buildings of note on the southern half of the block, were demolished in the early 1990s and replaced by the Jackson Center, which opened in 1992.

Researched and written by Amanda Davis, architectural historian