Connecticut View Establishments by Connecticut Cities

Connecticut's Green Book Heritage

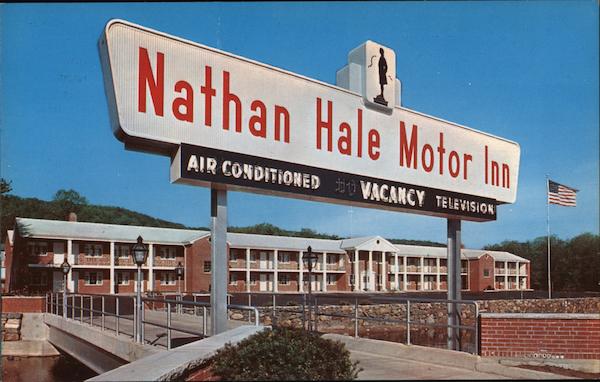

Throughout the duration of the Green Book, African American travelers often found themselves driving through Connecticut on their way from New York to Boston. In the 1938 edition, the section listing Connecticut sites is accompanied by a short passage advertising the newly constructed Merritt Parkway, built to bypass the old Boston Post Road: "Motorists traveling from the South or West going to the New England States…connect with the Hutchinson River Parkway and then the Merritt Parkway…hence saving much time." Twenty years later, with the opening of the Connecticut Turnpike (Interstate 95), along a slightly more southerly course, The Green Book advertised a new group of easily accessible hotels, motels and restaurants for those traveling through the state.

Connecticut was also home to its own tourist attractions and destinations. Several editions of The Green Book had a section at the back entitled "Summer Resorts" or, later, "Vacation Section", which contained Connecticut listings. Some people may have been headed towards the West Haven beaches, as made evident by the sheer number of seaside hotels listed in The Green Book (none of which survive today). Others may have been traveling to New Haven for the rich jazz scene. And in at least one case—Camp Bennett in South Glastonbury—the listing was a destination itself.

However, from the beginning, Green Book listings weren't just for travelers headed to other states or vacation locales. The predominance of listings were in urban centers with African American communities and neighborhoods, including the inland destinations of Hartford and Waterbury. Many of these sites not only catered to tourists, but to Black migrants from the South who needed help assimilating to life in Northern urban centers. During the Great Migration that started around 1910, southern African Americans relocated to states such as Connecticut in search of better employment opportunities. With the onset of World War I, as able-bodied White men were sent overseas, Black migrants, as well as women, filled jobs within the industrial sector. A similar pattern emerged during World War II, with the expansion of the national defense industry and other wartime economies.

These waves of migrants established vibrant African American communities throughout industrial and large coastal cities across Connecticut. The growth and geographic concentration of the African American population was matched by the emergence of businesses and social organizations, many of which would be listed in The Green Book. For example, the Pearl Street Neighborhood House in Waterbury was a community center located within one of the city's largest Black neighborhoods. Local community members accommodated migrants as well as travelers and also engaged in Civil Rights advocacy. Over time, these communities and businesses expanded beyond urban centers and by the late 1950s, businesses in rural areas, such as Moodus, Pomfret, and Sharon, were included in Connecticut's Green Book entries.

While racism and Jim Crow are typically associated with the south, Black people traveling through northern states were not exempt from segregation or racial violence. For instance, the KKK was active throughout Connecticut in both major cities and rural areas until the 1980s. African American travelers passing through Connecticut on their way between New York and Boston were advised to stick to major highways and avoid stopping in small towns. There are numerous anecdotes in which Black people were denied service in some hotels and establishments. As such, The Green Book was as much of a necessity in Connecticut as other states across the country.

Over the 28 years of The Green Book's publication, 122 Connecticut businesses were listed in the guidebook. These establishments represented a full spectrum of amenities, including hotels, tourist homes, restaurants, gas stations, and beauty parlors. Most of Connecticut's Green Book sites were located in major urban centers: Bridgeport, Hartford, New Haven, New London, Stamford, and Waterbury. Over half of these sites have since been demolished, and very few are recognized by the National Register of Historic Places. Of those that are listed in the Register, almost none cite African American history as an area of significance, and none mention The Green Book. Very few are recognized on the Connecticut Freedom Trail. Many of the demolished sites were lost during the urban renewal movement in which city planners sought to clear out so-called "slums," disproportionately dispossessing African American families in the process.

For more on the history of Black migration to Connecticut, see "Southern Blacks Transform Connecticut," at Connecticut Explored ( https://www.ctexplored.org/southern-blacks-transform-connecticut/)

Preservation Connecticut interns Daniella Occhineri, of Southern Connecticut State University, and Cecelia Puckhaber, of Central Connecticut State University, researched and documented Connecticut's existing Green Book sites during the 2023 spring semester. Their work built upon previous research conducted in 2017 by Alyssa Lozupone, formerly of the Connecticut State Historic Preservation Office, and Chris Wigren, Architectural Historian and Deputy Director, Preservation Connecticut, in 2016. Overall management of the 2023 project was by Renée Tribert, Preservation Services Manager at Preservation Connecticut. The information about Connecticut sites was provided to "The Architecture of The Negro Travelers' Green Book" project leaders in August 2023.