Maryland View Establishments by Maryland Cities

Maryland: A Respite through Travel, Recreation and Entertainment

Africans and African Americans, both free and enslaved, have been resident in Maryland since the seventeenth century. Before the American Revolution, freed people lived in independent communities in Baltimore, Frederick, and Snow Hill, to name a few locations. By the time the Civil War started, Baltimore had more freed than enslaved people living within city limits. Better economic opportunities at the beginning of the twentieth century caused many African Americans to leave the Eastern Shore and Southern Maryland, and migrate to Baltimore.

Enactment of the 1904 Jim Crow law for Baltimore streetcars reinforced Maryland’s identity as a hostile state for African Americans. Racism led to the establishment of local KKK groups and culminated in the lynchings of three men in the early 1930s: Matthew Williams and an unknown man in Salisbury, Wicomico County, on December 4, 1931, and George Armwood in Princess Anne, Somerset County on October 18, 1933 (https://www.mdlynchingmemorial.org/lynchings-in-maryland).

Despite the violence, some African Americans came together to work towards better social and commercial opportunities in towns such as Turner’s Station, Frederick, and Waldorf. After the lynchings, Green found owners near US 13 willing to list their businesses in Salisbury in 1938 and in Princess Anne in 1949. The Green Book included accommodations for Frederick, Hagerstown, Upper Marlboro and Baltimore beginning in 1938. In all, 103 sites in 26 Maryland towns were listed between 1938 and 1966/1967.

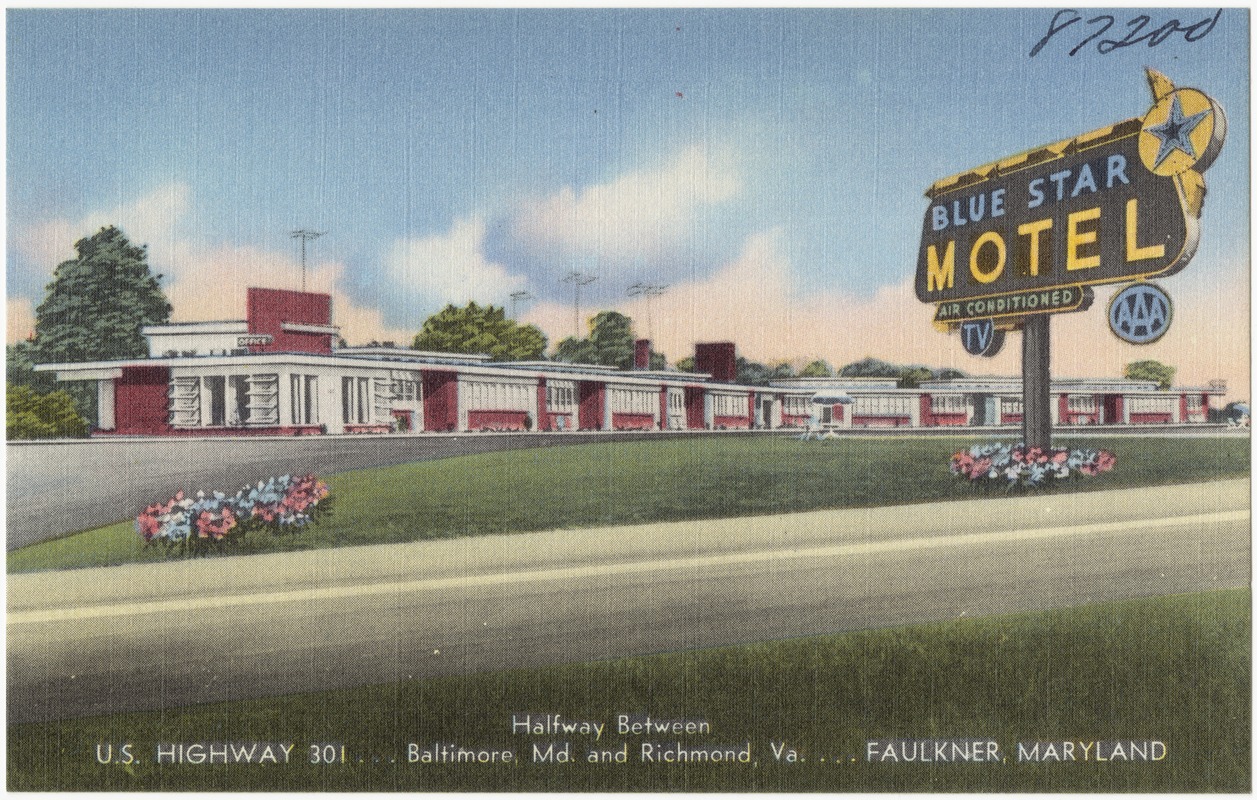

Green's listings kept travelers on known highways such as US 40 from Baltimore to Cumberland or US 301 from Baltimore to Upper Marlboro, Waldorf and Faulkner. One contentious spot in 1961 was along US 40 in Edgewood in northeast Maryland where white restaurant owners refused service to African diplomats traveling to Washington, DC, causing great diplomatic embarrassment to President John Kennedy. Maryland’s Open Accommodations Law, which was passed in 1963 in the aftermath of this event, benefitted both traveling Africans and African Americans.

Green regularly revised the listings for Maryland, adding or removing names as businesses opened or closed. Many of the buildings date from the nineteenth century and reflect succeeding layers of control as whites left and African Americans began their occupation. Listings also include resorts along the Chesapeake Bay that appealed to well-known musicians on the Chitlin Circuit, accommodations in Hagerstown for young baseball players, and sites reflecting the involvement of Frontiers of America and NAACP members in each town. These businesses demonstrate the abilities and strength of Maryland’s African American communities during the mid-twentieth century, as they sought respite through travel during a time of struggle for basic rights as American citizens.