Following the formation of African American regiments across the wartime Union in the spring of 1863, leading Black abolitionists, from William Wells Brown to Robert Hamilton to Frederick Douglass, put aside their past, contentious disagreements over the issue of enlistment. The Union, they now all agreed, had finally proven itself deserving of Black military service. Now that the nation was willing to accept Black volunteers, moreover, activists were anxious not to let the moment go to waste. As Brown, a former vocal opponent of enlistment, argued at a meeting in New Bedford, Massachusetts, if African Americans “permitted this opportunity for themselves to pass, they would forever be left out in the cold.” African Americans, he believed, needed to seize the chance before them, proving their worthiness for full and equal rights through martial valor. Alongside Robert Hamilton, Frederick Douglass, George T. Downing, and myriad other Black abolitionists, Brown thus threw himself into military recruiting with gusto. Over the next two years, these activist recruiters would journey across the North and Union-occupied South, inducing both free-born and newly-freed African Americans to join the Union ranks.[1]

As they set about on their travels, these activists encountered a disturbing reality: Black recruits faced rampant, systematic discrimination, from unequal pay to being barred from advancement to commissioned officer status. Almost without exception, White officers would command the new Black regiments. Recruiters tolerated these severe shortcomings—at least at first. In New Bedford, Brown explained that “prejudice against the race must be overcome by degrees.” As he hoped, time, and the crucible of Black martial sacrifice, would change Union policies for the better. By the summer of 1863, however, as such policies continued unabated, many Black abolitionists began to lose patience. When Lincoln failed to respond to an edict from Confederate President Jefferson Davis, ordering that captured Black troops be treated as rebellious slaves, Douglass took to his newspaper columns in outrage. “When I plead for recruits, I want to do it without qualification. I cannot do that now,” he declared. It would take an August personal meeting with Lincoln, who finally took measures to ensure equal protection of Black troops, to bring Douglass back into the recruitment fold. Nevertheless, the fight for equality would not be as seamless as Douglass had once imagined. The unequal pay issue would take longer to rectify: Congress would not institute full, retroactive wages until June 1864, more than a year since recruitment began. And commissioned officer status would remain elusive, with the hundred or so commissioned Black line-officers, chaplains, and surgeons encountering much resistance to their advancement from White Union authorities. Commissary Sergeant James T. S. Taylor, a Charlottesville cobbler who had fled his home and joined the army in Washington, D.C., wrote to the New York Anglo-African in early 1865 to protest the lack of commissioned officerships available to his fellow Black soldiers.[2]

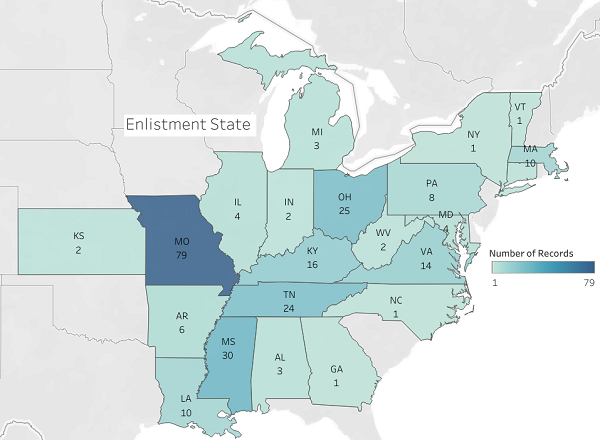

Despite the hurdles facing them, African Americans continued flocking into the Union ranks from across the war-torn nation, fighting against the rebellion as much as for freedom, equality, and citizenship. Among those heeding the calls of Douglass and other activists were more than 250 men born in Albemarle County, such as Daniel W. Carter, Stephan Washington, John Bolden Battles, and John Allen. As the accompanying map designed by Nau Center intern Matthew Weisenfluh illustrates, however, these men did not enlist in Albemarle County, but rather from dozens of locales spread across both the North and South. The patterns of American slavery, the domestic slave trade across the American Slave South, as well as escapes and relocations to the free North, help explain how such a far-flung geographical distribution came to be in the years before the Civil War.

Take, for example, the case of Carter, one of a number of Albemarle-born men to enlist in eastern Missouri. Carter, alongside many of these fellow enlistees, had been a slave of John Coles Carter, a wealthy planter born into the elite First Families of Virginia. In 1852, he had moved from Virginia to Missouri, establishing plantations across the fertile region known as “Little Dixie.” Daniel Carter had been part of this forced migration, leaving Albemarle and becoming one of more than 120 enslaved African Americans working on John Coles Carter’s plantations in Pike and Lincoln Counties. It was to a Union military recruiting station in Troy, the seat of Lincoln County, that Daniel Carter escaped in December 1863, enlisting in the 62nd United States Colored Troops (USCT). He became the first of an eventual eighteen enslaved, Albemarle-born African Americans from Carter’s Missouri plantations to join the Union war effort.[3]

Other Black Virginians in Blue, such as Washington, had experienced the horrors of the domestic slave trade, undergoing forced migrations from Albemarle to Louisiana and other Deep South states along the Mississippi River. In the decades before the Civil War, Virginia became the center of what was known as the slave-breeding industry, selling thousands of enslaved African Americans to the Old Southwest—the profitable frontier of the Slave South. At the center of this expanding slaveholding empire was the Mississippi River. The river, as the historian Walter Johnson has discussed, was the lifeblood of the region, its main avenue for transporting both lucrative cash crops like cotton and sugar and enslaved Black bodies. That Washington, born in Charlottesville in 1833, ended up at some point before the Civil War in Bayou Lafourche, Louisiana, a booming region of sugar plantations close to the riverine slave-trading hub of New Orleans, was likely no coincidence. What is certain is that Washington enlisted in the Union military at the earliest possible moment, joining the 3rd Louisiana Native Guards Infantry Regiment in November 1862, following the capture of New Orleans. He would be one of at least ten Albemarle-born African Americans to join the Union Army in Louisiana.[4]

While Carter and, likely, Washington had voted with their feet, escaping from slavery to enter the Union military, other Black Virginians in Blue had enlisted in the free North. The Old Northwest, especially Ohio, was another epicenter of the Black diaspora from Albemarle, welcoming mostly free-born or freed African Americans. Virginia, as a slave society, was overwhelmingly inhospitable to free Blacks, who defied its clear-cut racial hierarchy. Battles, born free in Charlottesville in 1833, had no doubt fled such conditions when he moved with his family to Ohio in the 1850s. Following the death of their parents, John and his brother, James, had moved on to Michigan, where they enlisted in the Union military in 1864. The Jackson brothers, Manuel and Alexander, had also relocated with their family from Albemarle to Ohio before the war, staying—and enlisting in the Army from—that state. Unlike the Battles, the Jackson brothers likely had the decision to leave Virginia made for them: their parents had been manumitted from slavery around 1854, and as such were required by law to leave the state.[5]

While the Battles and Jackson families had relocated to the free North on their own, other Albemarle-born Blacks established communities together. Yet another epicenter of the Albemarle diaspora was a freed Black community in western Pennsylvania known as Pandenarium. In 1854, Albemarle slaveholder Charles Everett manumitted his 63 slaves in his will, purchasing a tract of land in Mercer County, Pennsylvania on which they could settle after they left Virginia. Aided by local abolitionists, this burgeoning community of Pandenarium soon thrived. Allen, who had left Virginia with his family as a child, became a manual laborer in the community. In 1864, he, along with two other Pandenarium residents, enlisted near Philadelphia in the 127th USCT. These Albemarle-born Blacks would return to Virginia as soldiers, serving in the campaigns of the Army of the James—and helping destroy the institution of slavery in their native state.[6]

Through their enlistments from across the nation, Albemarle-born Black soldiers sought to make the dreams and aspirations of activists like Brown and Douglass a reality—to ensure liberty and equality for future generations. This struggle for equal rights proved to be long and difficult, remaining far from finished by the end of the war. Through their sacrifices, however, the African American recruits of the Albemarle diaspora nevertheless helped make such change possible. Dispersed by the unmitigated horrors of slavery from their home state, these Black Virginians in Blue ended up playing parts in the fight for freedom across the nation as a whole.

Images: (1) Map of BVIB Enlistment Places by State, (2) Map of BVIB Enlistment Places by Cities (designed by Nau Center intern Matthew Weisenfluh (UVA 2020)).

[1] “War Meeting in New Bedford,” Weekly Anglo-African, February 28, 1863. See Debra Jackson, “A Black Journalist in Civil War Virginia: Robert Hamilton and the ‘Anglo-African,’” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 116, no. 1 (2008): 42-72; Brian M. Taylor, “To Make the Union What It Ought to Be”: African Americans, Civil War Military Service and Citizenship (Doctoral Dissertation, 2015); L. Diane Barnes, “Make Mine an Abolition War: George Luther Stearns, Frederick Douglass, and the Black Soldier,” in Paul Finkelman and Donald R. Kennon, editors, Congress and the People’s Contest: The Conduct of the Civil War (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2018), pp. 185-204; David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2018); and Elizabeth R. Varon, Armies of Deliverance: A New History of the Civil War (New York: Oxford, 2019).

[2] “War Meeting in New Bedford,” Weekly Anglo-African, February 28, 1863; “The Commander-in-Chief,” Douglass’ Monthly, August 1863; James T. S. Taylor, “From the Second Regiment U.S.C. Infantry,” Weekly Anglo-African, February 25, 1865; See David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass’ Civil War: Keeping Faith in Jubilee (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1989); James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics (New York: W.W. Norton, 2007); and Blight, Prophet of Freedom.

[3] Elizabeth R. Varon, “From Carter’s Mountain to Morganza Bend: A U.S.C.T. Odyssey, Part I,” Nau Center for Civil War History Blog, January 11, 2017 (https://naucenter.as.virginia.edu/blog-page/406). Also see Alan Taylor, The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772-1832 (New York: W.W. Norton, 2013).

[4] Casey Bowler, “‘Begging Their Chance to Lead the Charge’: Black Virginians and the Louisiana Native Guards,” Nau Center for Civil War History Blog, November 28, 2018 (https://naucenter.as.virginia.edu/blog-page/931). Also see Walter Johnson, River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2013).

[5] Matt H. Wallace, “Bittersweet: Black Virginians in Blue at the Battle of Honey Hill and Beyond,” Nau Center for Civil War History Blog, December 4, 2018 (https://naucenter.as.virginia.edu/blog-page/936). For the difficulties facing freed blacks in Virginia, see Eva Sheppard Wolf, Almost Free: A Story About Family and Race in Antebellum Virginia (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2012).

[6] Jane Diamond, “Politics in Pandenarium: An Albemarle Plantation, a Free Pennsylvania Settlement, and the U.S. Colored Troops,” Nau Center for Civil War History Blog, November 2, 2017 (https://naucenter.as.virginia.edu/blog-page/661).