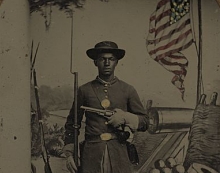

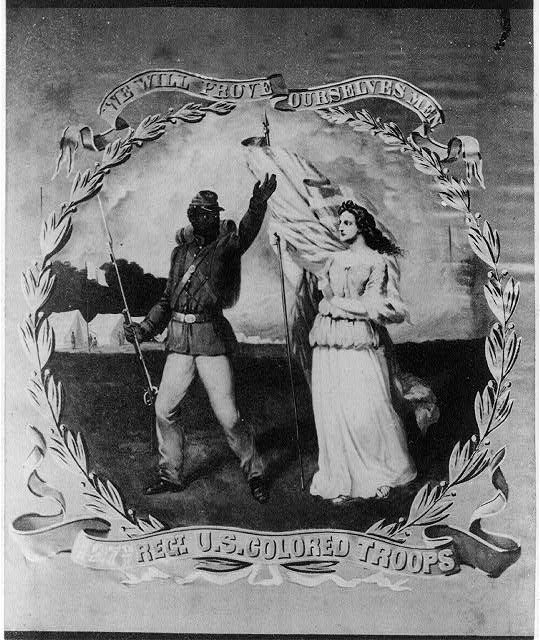

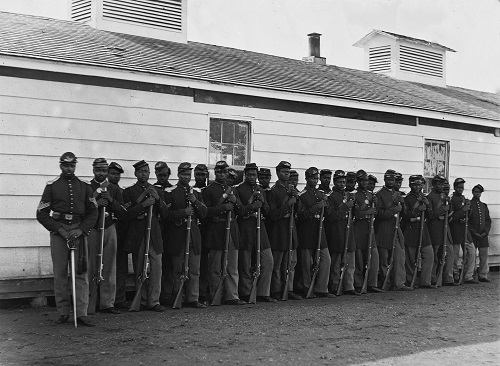

Approximately 180,000 African American men enlisted in the Union Army during the Civil War. In examining compiled military service records online at Fold3.com or at the National Archives, we have so far discovered that 252 of these Black soldiers were born in Albemarle County, Virginia. Of those Albemarle men, 72 died while serving in the army, a 28.6% mortality rate that is significantly higher than the 18.5% figure for all USCT soldiers.

If this is your first visit to Black Virginians in Blue, we recommend that you read the overview essays by Casey Bowler and Frank Cirillo first before exploring the others. Essays include deeper explorations of noteworthy Albemarle Black soldiers and sailors, regimental histories, battle narratives, and cover such topics as disease, Black family life, and our project's methods. In order to filter essays, unclick the checkmark next to the types of essays (overview, people, places, or battles) that you do not want to see. Essays can be searched for keywords by using the search bar in the site's header.

Black Virginians in Blue (Part I): Before the Civil War

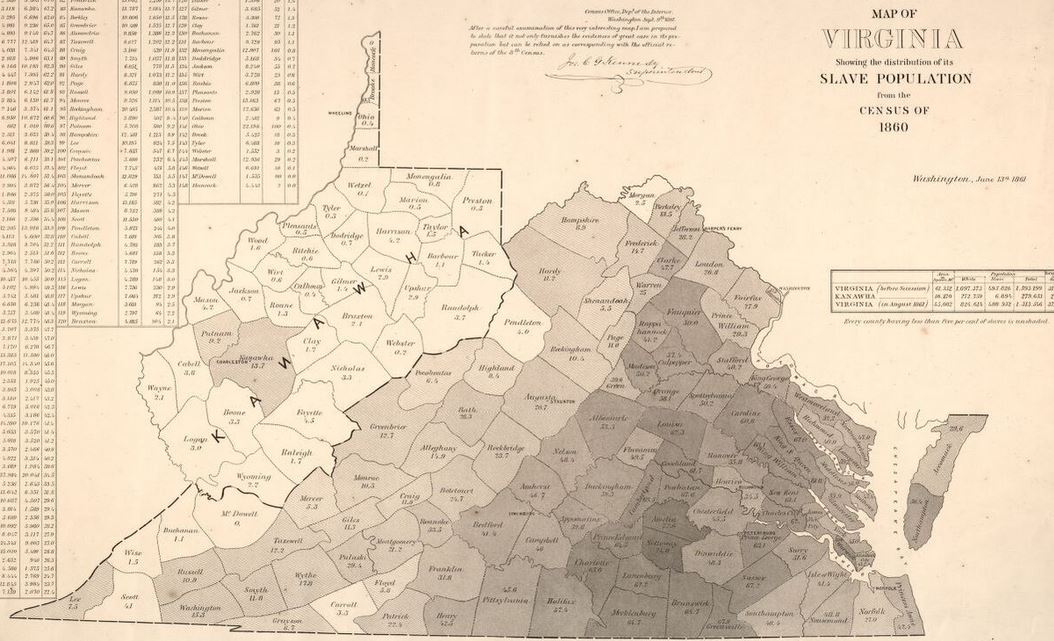

In the years preceding the Civil War, White Virginian society was highly stratified and deeply invested in the preservation of its slaveholding tradition. Slavery was the foundation for nearly all of the state’s agricultural, industrial, and economic growth. Slaves living on plantations dealt with severe working conditions and insufficient rations, and the threat of southern sale or westward movement constantly hung over them. Free Virginians of color faced similar instability, as their right to reside in the state was frequently called into question. These challenges led to a way of life characterized by continuous movement and fluctuating legal status. Black Virginians, whether enslaved or free, had to find ways to navigate a social and political system intent on maintaining their subordination. Many Albemarle-born African Americans went on to serve in the war, enlisting in the United States Colored Troops (USCT).

Black Virginians in Blue (Part 2): The Civil War

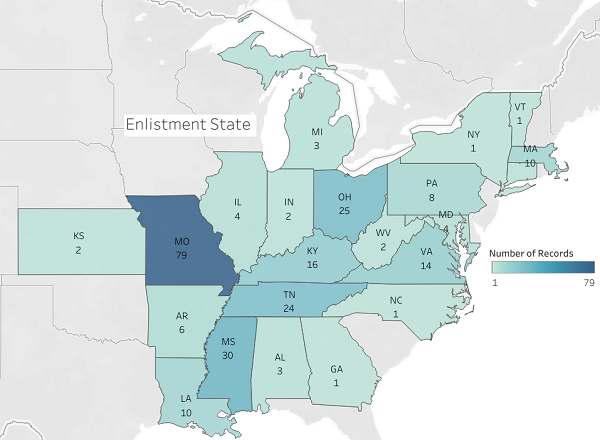

The beginning of the war in Albemarle saw Black Virginians outnumbering the 12,103 Whites in the county. There were 13,916 slaves and 606 free people of color living in Albemarle in 1860. As thousands of White men left to serve in the Confederate military, African Americans increasingly represented a larger proportion of the population, leading to even harsher laws and regulations restricting their movements and livelihoods. Amid this turmoil, many Black Virginians began enlisting in the Union military. Geographically spread throughout the country — either of their own volition or because of the slave trade—these men found their way to recruiting stations across the United States or Union-occupied areas to fight against the Confederate cause.

Black Virginians in Blue (Part 3): After the Civil War

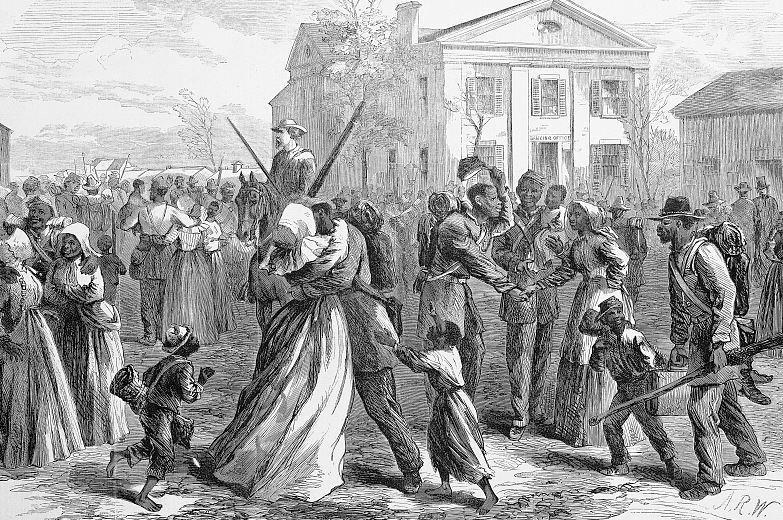

The end of the war brought major changes to Virginia, with emancipation freeing the state’s sizeable slave population and necessitating the restructuring of its social and economic systems. But this change was not immediate—it took years of work by Black Virginians to establish their place in the communities that had fought to uphold their enslavement. This was a time characterized by movement and flux for African Americans, as soldiers returned home, families reunited, and the fight for Black civil rights continued. The Nau Center currently knows of four USCT soldiers who returned to Albemarle County after mustering out: James T. S. Taylor, Nimrod Eaves, William Page, and, briefly before moving to Richmond, William I. Johnson. Most of the sailors and soldiers born in the county, however, returned to live where they had resided at the time of their enlistment, including other parts of Virginia and across the North and South, with a few also living in the West. These men exemplify the typical struggles and triumphs that most Black Union veterans, regardless of birthplace or post-war residence, experienced in the decades after the Civil War was won.

“Let the Black Man Get an Eagle on His Button, and a Musket on His Shoulder”: The Long Road to African American Military Service, Part I

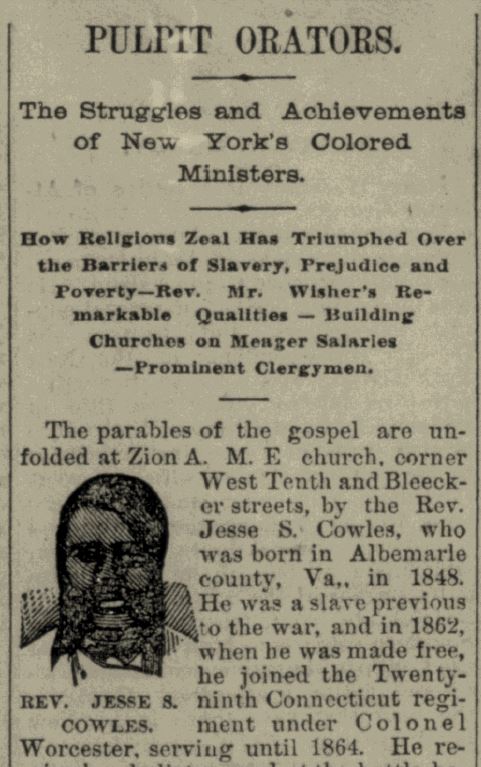

When the Civil War began in April 1861, it was far from a foregone conclusion that Albemarle County natives like Jesse Cowles and Mathew Gardner would end up serving in the Union military. Over the first two years of the war, African American abolitionists fought an uphill battle against a reluctant Lincoln administration and a prejudiced Northern public to allow Black enlistment. Only through their strenuous efforts, alongside the exigencies and political calculations of the larger conflict, did their dream of military service eventually become a reality.

The Long Road to African American Military Service, Part II

In the two years following the start of the Civil War in 1861, African American activists and their allies engaged in a sustained, strenuous crusade to persuade the White northern public—and, by extension, the Lincoln Administration—to support Black military enlistment. Their untiring efforts, in combination with larger military developments, ultimately shifted the tide of public opinion, helping bring about a national policy of Black military service by 1863.

The Enlistment Map: The Long Road to African American Military Service, Part III

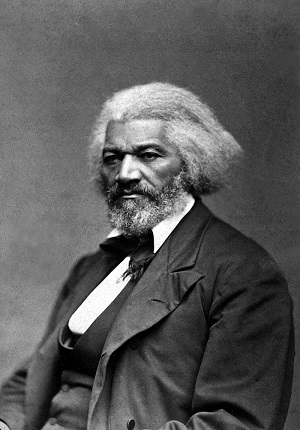

Following the formation of African American regiments across the wartime Union in the spring of 1863, leading Black abolitionists, from William Wells Brown to Robert Hamilton to Frederick Douglass, put aside their past, contentious disagreements over the issue of enlistment. The Union, they now all agreed, had finally proven itself deserving of Black military service. Now that the nation was willing to accept Black volunteers, moreover, activists were anxious not to let the moment go to waste.

Slave Marriage, Free Marriage: Black Veterans and Their Families After the Civil War

The lack of official records is a distinct limitation for research into the lives of formerly enslaved Black veterans born in Albemarle County. Many obstacles stood in the way of securing official documents: their marriages, deaths, and baptisms were less likely than those of Whites to be publicly recorded; illiteracy meant that it could be difficult to preserve such knowledge except through oral transmission; and the domestic slave trade often split families across the country. Pension documents, however, can provide valuable insight into the relationships and family structures of Albemarle-born USCT veterans, since they are composed of medical examinations, military service summaries, and depositions that corroborate family relationships.

Black Virginians in Blue and Civil War Memory

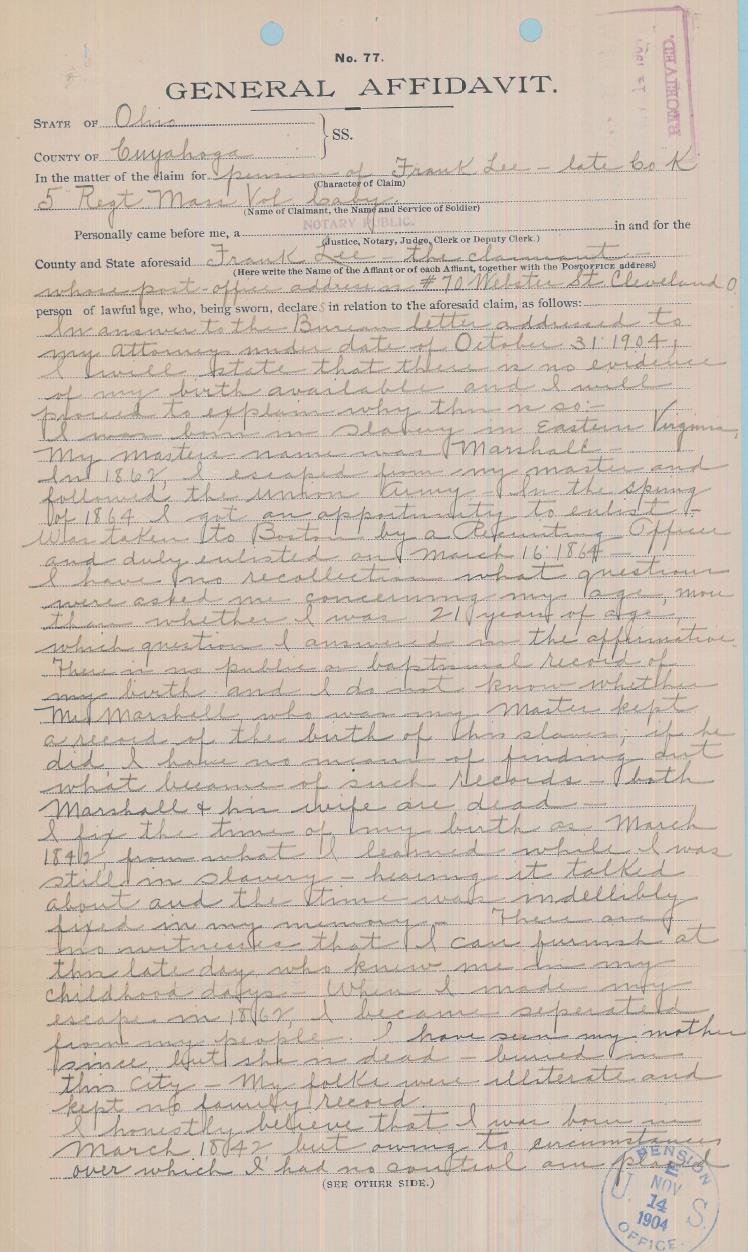

In 1915, a prominent African American newspaper, The Chicago Defender, reported on a memorial gathering of the St. John’s AME Sunday school in Cleveland, Ohio. The current school superintendent, the article noted, began by invoking an address given fifteen years earlier by his predecessor, Frank Lee. Born into slavery in Albemarle County, Lee had escaped bondage and entered the Union ranks during the Civil War. In the decades after his service, he established himself as one of the leading members of Cleveland’s Black elite.

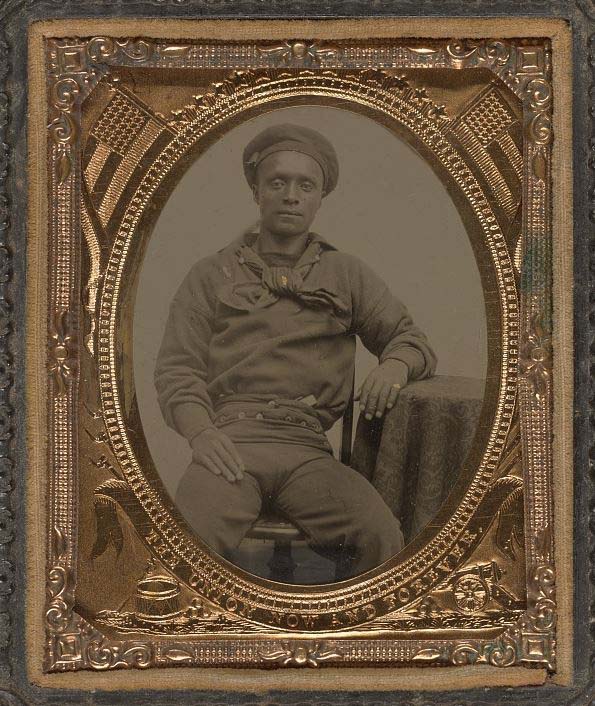

Black Virginians at Sea: Albemarle County’s African American Union Sailors

Out of the approximately 18,000 African American sailors who served in the Union navy during the Civil War, over 2,800 were born in Virginia, the most from any state. While most of the men in our Black Virginians in Blue project were soldiers in the USCT, six served as sailors aboard five Union vessels. Through the use of naval service records, accessed through the National Park Service’s Soldiers and Sailors Database, and secondary sources on the wartime navy and Black sailors, we have produced a preliminary reconstruction of the wartime experiences of our Albemarle sailors. Black sailors greatly aided the Union war effort because they provided much needed labor on ships that helped defeat the Confederacy.

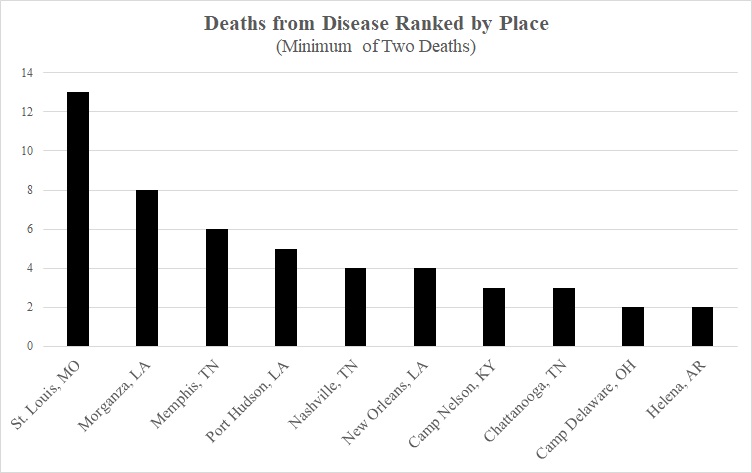

"Quite Unhealthy": Deadly Diseases Among Albemarle-born Black Soldiers (updated)

A Word on Methods: Recovering the Stories of Black Virginians in the Union Army and Navy (updated)

The Nau Center's former Digital Historian Will Kurtz used digital resources to make substantial progress in researching the lives of Black Union soldiers from Albemarle County, Virginia, prior to making a research trip to the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Thanks to his research and tips from local researchers, the project was able to identify 251 Black soldiers and 6 Black sailors with Albemarle County roots. This essay succinctly describes the overall project's research and methodology. (Updated May 18, 2021)

From Carter’s Mountain to Morganza Bend: A USCT Odyssey (Part I)

What follows is a three part story, which we will present in consecutive blog posts, that permits us to see the history of central Virginia in a new way: with a focus on the journeys of African American men, born in the shadow of Jefferson’s Monticello, who fought for the Union army in the Civil War. These men represent the Virginia roots of thousands of USCT soldiers, men who were dispersed by the system of slavery and then converged, during the war, in Black regiments, and fought to save the Union and to end slavery.

From Carter’s Mountain to Morganza Bend: A USCT Odyssey (Part II)

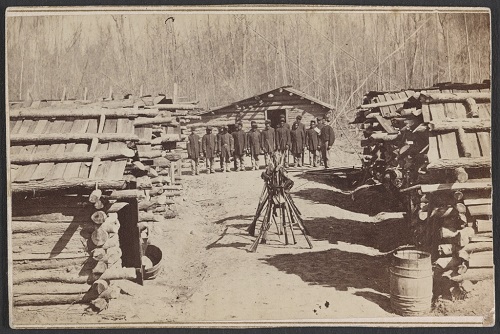

The 65th and 67th USCT Infantry Regiments were dispatched in March of 1864 from Missouri to Morganza Bend, Louisiana (a.k.a. Morganzia), a low-lying Mississippi river town nearly thirty miles from Port Hudson; the 62nd USCT Infantry Regiment, which was sent to Baton Rouge initially, arrived in Morganza in June. Port Hudson had been the scene of a stirring Union victory, in which the USCT had played a heroic role, in July of 1863. But the Missouri regiments at Morganza saw very little action, aside from some skirmishing by detachments. Their lot was to do garrison duty as an occupation force—building fortifications and gun emplacements, standing guard, cutting roads, repairing levees, and generally maintaining the camp defenses, in an oppressively hot and humid, muddy, mosquito-infested terrain.

From Carter’s Mountain to Morganza Bend: A USCT Odyssey (Part III)

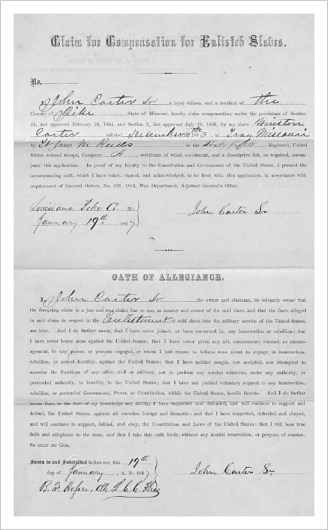

In the aftermath of the Civil War, as John Coles Carter and the USCT veterans from Albemarle County, Virginia, returned to Missouri, slavery and secession were dead letters but the “chattel principle”—the idea that slaves were property whose bodies carried a price—was not. In keeping with two acts of Congress (in 1864 and 1866) that allowed loyal slave owners to file a claim against the U.S. government for the loss of a slave’s value, John Coles Carter, his son John Carter, Jr., and their relative John W. Bankhead all filed claims in January of 1867, asking for $300 compensation for each slave who enlisted, including those who had perished in the war, to whom they had once held title.

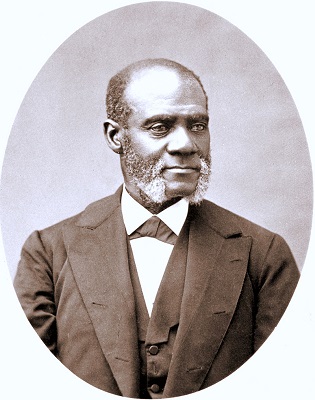

Matthew Gardner and the Struggle for Survival in Postwar Arkansas

In December of 1915, the Black community of Jefferson County, Arkansas, gathered to bury the esteemed Black Virginian in blue Matthew Gardner (alias Berry). Gardner had been born a slave in Albemarle County. Forced by the slave trade to move to Arkansas on the eve of the Civil War, Gardner fled bondage during the conflict, enlisting as a member of the United States Colored Troops (USCT). After the war, Gardner returned home to an Arkansas Delta in flux, where the ambitions of a Reconstruction coalition that included Blacks ran aground on the festering racial resentments of most White southerners. Girded by the support of wartime comrades and the local Black community that would later lay him to rest, Gardner endured throughout the chaotic ensuing decades, navigating between the shoals of the largely failed promises of Reconstruction, the dangers of white supremacist violence, and the pressing problem of poverty. His story thus exemplifies the sacrifices, sufferings, and survivals of African Americans in postwar Arkansas.

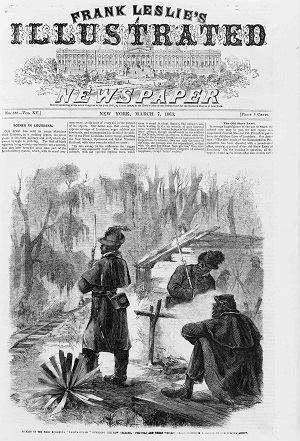

“Begging Their Chance to Lead the Charge”: Black Virginians and the Louisiana Native Guards

Narratives of African American men in the Civil War usually begin in 1863, with the establishment of the Bureau of Colored Troops and the Federal push for the enlistment of Black soldiers into the Union army. For Black men in Louisiana, however, involvement began over two years earlier, with the formation of a Confederate militia to be drawn from the state’s significant population of free men of color. They were called the First Native Guards. This organization would disband a year later when New Orleans fell to Union forces, but some of the men who had served in the militia would go on to become the first Black soldiers to enlist in the Union army in 1862. They were designated the Louisiana Native Guards, and their service became a litmus test of Black soldiers’ suitability for military participation in the Civil War. Black Louisiana regiments were faced with significant hardship throughout and after the war, including inadequate supplies, hostile reactions from White civilians and fellow Union soldiers, the forcing out of Black commissioned officers, and insufficient pensions. Despite these challenges, the soldiers persevered and demonstrated that if given the chance to fight for their freedom, they would do so admirably.

“Brave Boys of the Fifth”: The Service of Two Black, Albemarle-Born Soldiers of the Famous 5th Massachusetts Cavalry Regiment

In 1905, forty years after the end of the Civil War, an Albemarle-born, African American veteran named Frank Lee applied to receive an increase in his pension. He had served as a young man in the 5th Massachusetts Colored Volunteer Cavalry Regiment, a Black regiment that fought for the Union cause. Because of his service, he was eligible for government assistance in the form of pensions, but he needed to verify one thing: his date of birth.

Patriots in Pandenarium: An Albemarle Plantation, a Free Pennsylvania Settlement, and the U.S. Colored Troops

In August 1864, three men named John Allen, James H. Garland, and George W. Lewis enlisted in Company A of the 127th Regiment United States Colored Troops (USCT). They were young—giving their ages as 17, 20, and 26, respectively on their enlistment papers—and all lived in Mercer County in western Pennsylvania. They were from a local community named “Pandenarium,” although all three had actually been born far to the south in Albemarle County, Virginia.

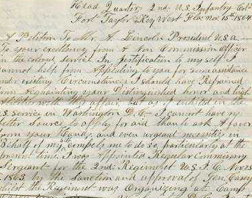

A Black Soldier from Charlottesville Writes to Lincoln

Confined at the headquarters of the 2nd U.S. Colored Infantry on November 15, 1864,Commissary Sergeant James T. S. Taylor put pen to paper to write President Abraham Lincoln a letter asking for release. “In Jestification to my self I cannot help from Appealing to you for some assistance under existing Circumstances,” wrote Taylor. “I should have Refrained from Acquainting your Distinguished honor and high Abilities with this affair, but as I enlisted in the U.S.”

Alexander Caine: From Philadelphia Barber to Union Sailor to World Traveler

Of the six Albemarle-born Black men who joined the Union navy during the Civil War, no one left behind a larger paper trail than Alexander Caine. Caine, a barber living as a freeman in Philadelphia at the war’s outbreak, joined the Union navy in January 1862 as a landsman and served on an ocean-going sloop called the USS St. Louis off the coast of West Africa.

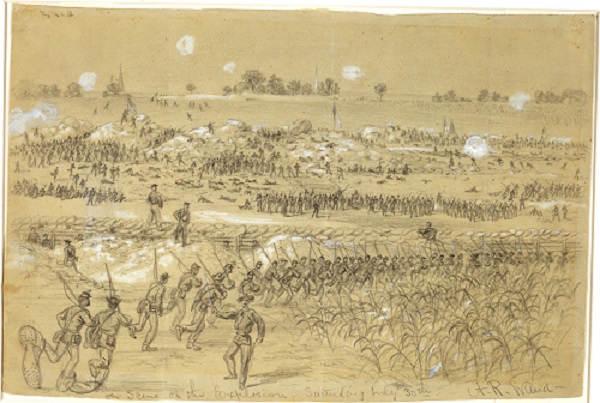

No Quarter Expected, No Quarter Given: The Brutal Experience of Black Virginians in Blue at the Battle of the Crater

On July 30, 1864, the Union army exploded a mine to expose a breach in Confederate lines at Petersburg in the hope of breaking the stalemate and ending the siege. The ensuing assault, which became known as the battle of the Crater, resulted in a Union failure and thousands of casualties in the worst racial massacre of the war. The Black troops of the United States Colored Troops (USCT) faced much greater danger at the Crater than their White Union counterparts.

Forgotten Triumph: Union Victories at the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm

Following the disaster at the Crater in the summer of 1864, Lieut. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant planned for another offensive late in the following September. Grant ordered Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler to lead an attack towards Richmond north of the James River with the goals of taking the city and diverting Robert E. Lee’s forces away from Petersburg. Grant told Butler, “The prize sought is either Richmond or Petersburg, or a position which will secure the fall of the latter.” Butler’s ensuing two-pronged offensive would result in the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm, also referred to as the Battle of New Market Heights, on September 29 and 30. Although not discussed much today, historian Douglas Crenshaw writes that in the victories at Chaffin’s Farm “the Union came closer to capturing Richmond than at any other time during the war,” potentially saving thousands of lives. Yet, the site of the battle remains, as described by National Park Service historian Mike Gorman, “one of the most important unpreserved battlefields around the Richmond area.” Despite United States Colored Troops (USCT) soldiers receiving fourteen of the twenty-five Medals of Honor that Black troops earned during the entire Civil War at Chaffin’s Farm, their bravery and heroism is likewise not well known.

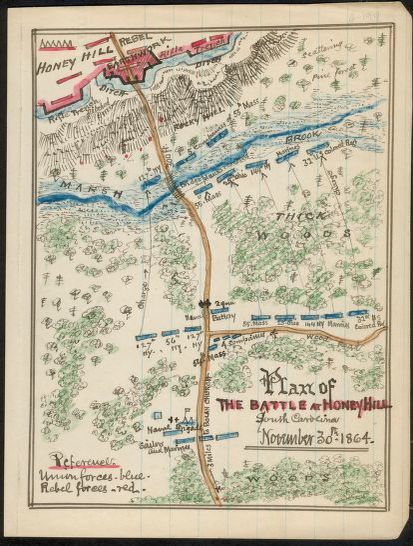

Bittersweet: Black Virginians in Blue at the Battle of Honey Hill and Beyond

After Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman took Atlanta in the fall of 1864, the Union army commenced Sherman’s famous “March to the Sea.” As an auxiliary effort to his main campaign, Sherman ordered an expedition up the Broad River in South Carolina. Sherman hoped to either cut the railroad between Charleston and Savannah in half, trapping the Rebels in Savannah, or spread a weakened Rebel force across the state. The resulting encounter between the Union and Rebel armies resulted in a Union defeat at the Battle of Honey Hill. Of the thousands of Black men belonging to the several regiments of United States Colored Troops (USCT) at the battle, eleven of them were born in Albemarle County, Virginia.

“The Question is Settled—Negroes Will Fight”: Albemarle County’s USCT Soldiers at the Battle of Nashville

In the late fall of 1864, Confederate General John Bell Hood led his defeated Army of Tennessee from the ruins of Atlanta. The aggressive Hood looked northward seeking to take back the initiative. Union forces in the state capital of Nashville, under the command of Major General George H. Thomas, represented a golden opportunity for an offensive operation. Thomas had approximately 50,000 troops under his command scattered throughout Tennessee and northern Alabama. Upon receiving news of Hood’s threat to Nashville, he began to concentrate his forces. Included in his reorganized Army of the Cumberland were approximately 8,000 troops under the command of Major General James B. Steedman detached from the District of the Etowah in eastern Tennessee. The division contained multiple United States Colored Troops (USCT) units, including nine soldiers originally hailing from Charlottesville or Albemarle County, Virginia.

Edward Rollins and the Second Battle of Fort Fisher

The Union capture of Fort Fisher, North Carolina, in January of 1865 was a major blow to the reeling Confederacy and set the stage for General Robert E. Lee’s surrender four months later. Black Virginians in blue were among the USCT soldiers who landed that blow.

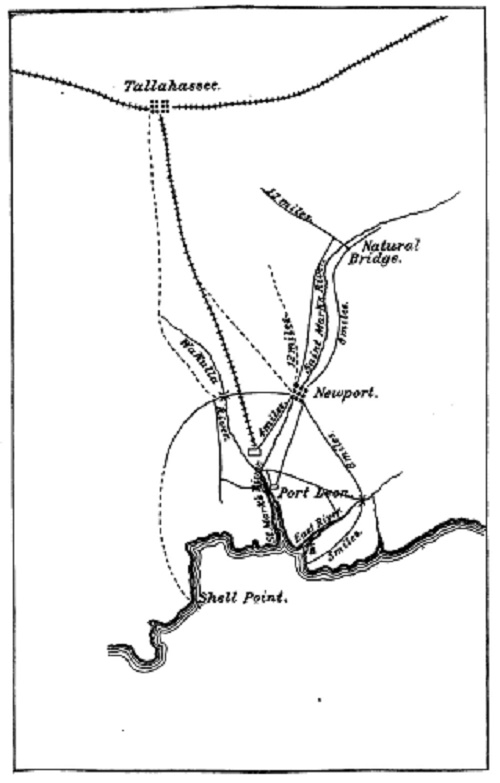

The Command Advanced Gallantly: The Battle of Natural Bridge

Despite major inroads made by Union armies across the South during the Civil War, the state of Florida existed largely on the periphery and experienced few major battles within its borders. As Florida was a sparsely populated state compared to its neighbors, and contained meager industrial resources, the Union did not prioritize an invasion to its inland portions. Strategically, devoting substantial resources to the state made little sense for the Union high command. As late as February 1864, only one major battle occurred within its borders—the Battle of Olustee or Ocean Pond.

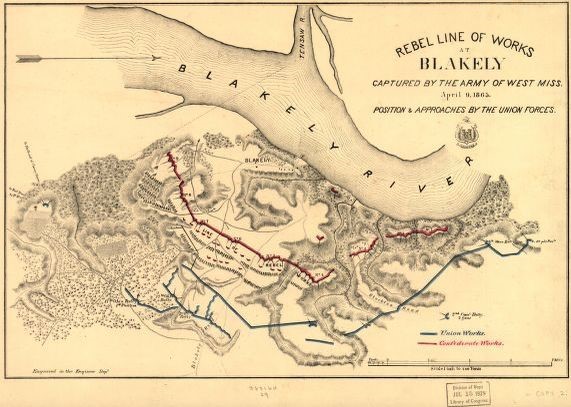

“I will bet on them every time”: The Men of the 68th USCT Infantry Regiment and the Battle of Fort Blakeley

The Battle of Fort Blakeley in Alabama took place in early April 1865 as the Civil War drew to a close, motivated by the Union desire to drive the Confederates out of their final holdings near the Gulf Coast. The seaport of Mobile Bay was no longer under Confederate control, but the city of Mobile itself still was, protected by the Confederate posts of Spanish Fort, directly to the east across the bay, and Fort Blakeley, about six miles to the north. In the end, nearly 16,000 Union soldiers fought to regain the fort, including some 5,000 members of the United States Colored Troops (USCT). This makes the assault on Fort Blakeley one of the battles with the largest proportion of USCT soldiers participating during the war. Nine African American soldiers present at the Battle of Fort Blakeley hailed from Albemarle County, Virginia.