The publication of Civil War soldiers and sailors databases online has been a major boon to genealogists for years. Civil War scholars also can benefit from these digital resources available at subscription and free sites. For example, many Civil War compiled military service records can be downloaded from Ancestry.com and its subsidiary site, Fold3.com. These records are important for recreating a soldier’s army career and also list important biographical information such as height, age, place of enlistment, birthplace, and rank. In some cases, these records indicate whether or not African American Union soldiers were freemen or slaves when they enlisted. For the Center's Black Virginians in Blue digital project, I started using digital resources way back in 2016 to make substantial progress in researching the lives of Black Union soldiers from Albemarle County, Virginia, prior to making our first research trip to the National Archives in Washington, DC.

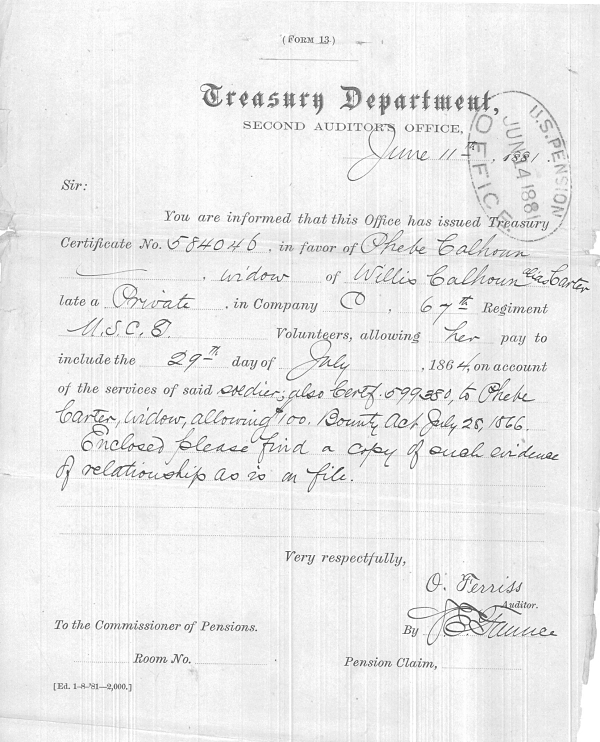

After speaking with archivist and historian Ervin L. Jordan, Jr., an expert in local Civil War history, and receiving a list of names that he had compiled as well as a few tips from the Center's then Associate Director Elizabeth Varon, I started to fill out a spreadsheet in Microsoft Excel of all of the Black men from Albemarle County who served in the Union army or navy. Dr. Varon found a transcribed descriptive list of all of the African American men who enlisted in U.S. Colored Troop (USCT) regiments in Missouri. Searching through the list yielded thirty-two results for “Albemarle County.” I found seven more for the misspelling “Albermarle” including Private Willis Calhoun who is pictured above. The realization that nineteenth century clerks often misspelled the county’s name proved useful as I continued to track down more men from Albemarle and its county seat, Charlottesville.

Initially, I hoped to rely on other freely available resources as much as possible. While the National Park Service does have a wonderful database of every Civil War soldier who served during the war, this website does not provide the soldier’s birthplace, age, place of enlistment, or other important biographical information. The site’s Black sailors' database did list such information, however, yielding six more men. In addition to doing a keyword search, I carefully reviewed every single record to make sure I did not miss any misspellings.

At this point, I realized that we would need to subscribe to Ancestry.com to access its database of USCT men. The U.S., Colored Troops Military Service Records, 1863-1865 database yielded over fifty men through a search for Albemarle County, VA. I then did a more general search for any man born in the state of Virginia, and I found many misspellings of places in Albemarle County. “Alabama County,” “Albermarle County,” “Sharlottesville,” and “Challetsville,” were some of the misspellings. In all, I found almost fifty more men this way, bringing the total through Ancestry.com to about one hundred. Another of the site’s databases, U.S., Descriptive Lists of Colored Volunteer Army Soldiers, 1864, helped us identify a few more men who enlisted in Kentucky-raised USCT regiments.

While a great resource, the main USCT database on Ancestry.com only contained records from the first fifty-five USCT infantry regiments, plus all of the Union’s Black artillery and cavalry units. In the first week of August 2016, I spent four days at the National Archives looking through the available USCT descriptive books for infantry regiments 56 through 138. These books, generally recorded twice for individuals companies as well as the larger regiment, list important biographical data about Union army soldiers at the time of enlistment. I added seventy-four more names to our growing Excel spreadsheet.

Unfortunately, dozens of these descriptive books for USCT infantry regiments 56 though 138 are either incomplete or missing at the National Archives. The only way to search for more Albemarle men at this point was to examine individual compiled military service records in the hopes that a descriptive book card had been filled out for the soldier prior to the disappearance of his company’s or regiment’s descriptive book. With the assistance of two University of Virginia undergraduates, Amelia Gilmer and Sarah Anderson, we searched through about thirty USCT infantry regiments by paging through digitized individual compiled service records located on Fold3.com. The process is tedious but much faster than ordering and examining these records at the National Archives. This search yielded only a relative handful of Albemarle-born soldiers, but was an important, if time-consuming, part of a process that I desired to be as thorough as possible.

Since concluding our main search, we have been told about a number of other soldiers from local historians such as Cinder Stanton and Alice Cannon of the Central Virginia History Researchers Group. Our most recent Black Virginian in Blues, Joseph Carr and Dabney O. Butler, were added to the project as a result of Alice's research and generosity in sharing her research with me. Blogging about our project as we worked on the website helped spread the word even further, leading to us gathering even more information about our soldiers. For example, after reading a blog that mentioned the Reverend Jesse S. Cowles (29th Connecticut Infantry), Samantha Dorm and the local historians at York History Center and the Friends of Lebanon Cemetery in York, Pennsylvania, reached out to us and helped us write a much more complete biograrphy of Cowles and his family. As of May 2021, we have found 251 Black soldiers and six Black sailors with Albemarle-roots.

In 2017 and 2018, we searched through two different pension file indexes (on Ancestry.com and Fold3.com respectively) to find pension records for as many of our men as possible. These records contain extremely rich information about soldiers’ post-war lives, their health and employment issues, as well as information about their wives, children, and other family members. Freelance researcher Jonathan Powell, Editorial Assistant Brian Neumann, and me all spent time at the archives looking for and copying pension files. I also took a trip to the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis to track down a few more files. Altogether, we have found 134 different pension application files that were filed on behalf of our soldiers and sailors or one of their family members (widow, dependent children, and parents). Albemarle's Black veterans were remarkably successful in receiving pensions, with a 93.9% success rate. While we were able to locate and copy most of these files, unfortunately a few were missing or have not been pulled due to the National Archives' closure during the pandemic.

Once we completed our initial list of all the Black men from Albemarle who served in the Union military, we entered data from their compiled military service records and pension files into a relational database designed and hosted by the Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities (IATH) at UVA. The database functions as the core of our project’s website, designed by Anne Chesnut and built out by IATH, that we published on April 13, 2021. The website now includes not just the basic biographical data from our initial database, but also individual student-written biographies for all of our soldiers, sailors, and their spouses; two interactive digital maps charting the places where they enlisted and mustered out of the army; contextual essays written primarily by our undergraduate interns; and dozens of primary sources transcribed by students and vetted by me. All of our amazing UVA undergraduate students' work has been reviewed by me, Editorial Assistant Brian Neumann, or the Nau Center's directors, Caroline Janney, Gary Gallagher, and Elizabeth Varon. Altogether, five UVA graduate students and fifteen undergraduates assisted the Center in finishing the project. Their work would not have been possible without the generous support of the Center's donors and the Jefferson Trust. In the future, we will add lesson plans that will make the site even more useful to Virginia high school teachers.

We hope that Black Virginians in Blue will prove to be an excellent resource for historians, genealogists, and the public, allowing anyone to search freely and learn more about this important, but sorely neglected, part of Albemarle County’s Civil War story. If anyone would like more information about our Black soldiers, sailors, or their families, or has additional genealogical data to share, please contact the Nau Center at naucenter@virginia.edu.

(This essay has been updated on May 18, 2021 by the Center's Digital Historian William Kurtz to reflect the project's development, growth, and completion as of its April 13, 2021 launch).

Compiled Service Records, RG 94 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. (hereafter NARA), accessed for each Black soldier through Fold3 (https://www.fold3.com/browse/273/); USCT Regimental Descriptive Books, RG 94, NARA; Pension Records for Civil War Soldiers, RG 15, NARA; “Search for Sailors,” Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System database, National Park Service (https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-sailors.htm); “U.S., Colored Troops Military Service Records, 1863-1865,” Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/1107/); “U.S., Descriptive Lists of Colored Volunteer Army Soldiers, 1864,” Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/2132/); "Descriptive Recruitment Lists of Volunteers for the United States Colored Troops for the State of Missouri, 1863-1865," St. Louis County Library (https://www.slcl.org/content/descriptive-recruitment-lists-volunteers-united-states-colored-troops-state-missouri-1863-18).