When the Civil War began in April 1861, it was far from a foregone conclusion that Albemarle County natives like Jesse Cowles and Mathew Gardner would end up serving in the Union military. Over the first two years of the war, African American abolitionists fought an uphill battle against a reluctant Lincoln administration and a prejudiced Northern public to allow Black enlistment. Only through their strenuous efforts, alongside the exigencies and political calculations of the larger conflict, did their dream of military service eventually become a reality.

From the start of the Civil War, many Black abolitionists clamored for the Union military to allow African Americans into its ranks. As historians have discussed at length, African Americans viewed military service as a means to citizenship and equality. Through martial prowess, Blacks hoped to prove to the skeptical, prejudiced White majority that they were worthy for inclusion into the American polity as free and equal citizens. By enlisting, the prominent Black Philadelphian Alfred M. Green noted in May 1861, African Americans would follow the examples of their forefathers who had fought in the Revolutionary War and War of 1812. The current generation would “create anew our claim upon the justice and honor of the Republic,” reminding the nation that African Americans had fought for its freedom from the very beginning, with little recognition and reward for their patriotism. The time had come, they implied, to redress this wrong.[1]

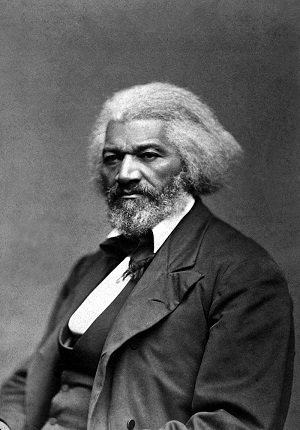

Black proponents of military service, most of them men, made their cases in deeply gendered terms. Frederick Douglass, perhaps the leading proponent of Black enlistment, framed the endeavor in terms of masculine glory. “The speediest way open to us to manhood, equal rights and elevation, is this service,” he declared later in the war. Soldiering in defense of the Union would provide Black men with an ennobling sense of dignity and self-worth. It would also prove their value in the eyes of the nation at large. “Let the black man get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder,” Douglass concluded, and none could deny him the “right of citizenship in the United States.” Military service, he made clear, was a male enterprise that would earn Black men the right to vote. Black abolitionist women, however, also joined in the campaign. Charlotte Forten, a young educator and the scion of a famed Philadelphia activist family, recognized that “regiments of freedmen” could demonstrate to the nation that “true manhood has no limitations of color,” thereby helping create a more egalitarian future. Such inroads, she hoped, would benefit not only her male counterparts, but her entire race as well.[2]

Following the outbreak of the Civil War, Douglass, Green and other likeminded Black abolitionists pressed for African Americans to offer their immediate services to the Union. “Our men are ready and eager to play some honorable part in the great drama,” Douglass declared. To that end, Black reformers organized community meetings encouraging the formation of drilling regiments and reserve guard militias. In Philadelphia, Green led the way in organizing a volunteer regiment, which would then offer its services to military authorities. In doing so, Green stressed that he was not settling for the Union war as it was. The Lincoln Administration, he knew, fought solely to preserve the Union, bent on restoring rebellious Confederate states to the nation intact. Emancipation, not to mention Black rights, was not on its agenda. Racial prejudices remained rife, and slavery itself continued in the four Border States that had remained in the Union. “Our injuries in many respects are great,” Green summed up. Black enlistment, he hoped, would change things for the better. Through their sacrifices on behalf of the nation, Green believed, African Americans could turn a war for Union into one for freedom. His Home Guard unit, alongside others formed in cities throughout the North, were meant to lead the way.[3]

A number of Black abolitionists, however, refused to partake in such efforts. A prejudiced nation intent on maintaining slavery, these reformers argued, did not deserve their service, at least for the time being. Some, such as the Providence, Rhode Island businessman and civil rights activist George T. Downing, emphasized their love of the nation. At a May meeting in Boston, Downing declared that he yearned to “give his all to answer the call of duty.” Unlike Green, however, Downing refused to advocate enlistment, not to mention enlist himself, until the “removal of disabilities allowed [him] to do so on terms of equality.” Doing otherwise, he asserted, would gain Blacks nothing. African Americans, according to Downing, had to wait until the nation had proved itself worthy of their intended sacrifices before offering their services.[4]

Others, such as the novelist William Wells Brown, rejected the notion of Black enlistment altogether. At the same Boston meeting, Brown condemned Downing and likeminded activists for “going off without knowing the ground.” Such figures, he asserted, were themselves going too far in support of the Union. Even as they refused to advocate enlistment for the time being, Downing and his colleagues remained open to the eventual possibility of doing so—a fact that, to Brown, demonstrated their weak resolve. The Union, Brown averred, was, and always would be, a nation grounded in prejudice and inequality. It could never prove worthy of their sacrifices.[5]

As African Americans from Douglass to Brown struggled over the issue of enlistment, the Union authorities decided matters for them. In state after state, officials at every level of government rejected the offers of Black volunteers, grounding such refusals in ill-concealed notions of racial inequality. Black volunteers, they often argued, were neither real men nor citizens, and thus had no role in the nation and its conflict. While most such offers, and their concurrent rejections, came in the early months of the war, a later episode proved rather illustrative of the dynamics at play. In Cincinnati during the summer of 1862, White authorities issued a call for volunteers to defend against an expected Confederate invasion. Local African Americans responded, forming a Home Guard. Their offer, however, was met with derision. When one would-be soldier approached a police officer to volunteer his service, noting that every able-bodied male citizen had been called into duty, the officer responded, “You know damned well he doesn’t mean you. [You] ain’t citizens.” Cincinnati officials consequently browbeat the Home Guard to disband through implied threats of mob action.[6]

In effect, the authorities thereby proved the opponents of immediate enlistment correct. Whites were not prepared to extend to Northern free Black volunteers even the dignity of enlisting, let alone the rights of freedom or citizenship. The time for mobilizing Black communities as recruits had not yet arrived. Faced with such rampant, racist opposition, Douglass and other formerly optimistic Black abolitionists accordingly backed off their initial calls for immediate enlistment, adopting the position taken earlier by Downing. For the time being, Douglass and his antislavery coadjutors would refrain from asking Blacks to volunteer for a cause that spurned them. Instead, they would turn their attention to the White public, undertaking efforts to persuade Northerners to grant African Americans the respect they deserved—and, therefore, pave the way for Black enlistment in a moral cause—through any means necessary.[7]

Suggested Readings:

Berlin, Ira, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie S. Rowland, editors. Freedom’s Soldiers: The Black Military Experience in the Civil War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Dobak, William A. Freedom By the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops 1862-1867. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, 2011.

Jones, Martha S. Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Kantrowitz, Stephen. More Than Freedom: Fighting for Black Citizenship in a White Republic, 1829-1889. New York: Penguin, 2012.

Smith, John David, editor. Black Soldiers in Blue: African American Troops in the Civil War Era. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Varon, Elizabeth R. Armies of Deliverance: A New History of the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Images: (1) Frederick Douglass, (2) George T. Downing, and (3) William Wells Brown (courtesy Wikicommons).

[1] “Colored Philadelphians Forming Regiment,” Weekly Anglo-African, May 4, 1861. Historical studies of the motivations for black enlistment include David Blight, Frederick Douglass’ Civil War: Keeping Faith in Jubilee (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1989); Stephen Kantrowitz, More Than Freedom: Fighting for Black Citizenship in a White Republic, 1829-1889 (New York: Penguin, 2012); David Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2018); Martha S. Jones, Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018); and L. Diane Barnes, “Make Mine an Abolition War: George Luther Stearns, Frederick Douglass, and the Black Soldier,” in Paul Finkelman and Donald R. Kennon, eds., Congress and the People’s Contest: The Conduct of the Civil War (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2018), pp. 185-204.

[2] “Speech of Frederick Douglass,” Liberator, July 6, 1863 and Charlotte Forten, “Life on the Sea Islands, Part II,” Atlantic Monthly XIII (June, 1864): 666-76.

[3] “Black Regiments Proposed,” Douglass’ Monthly, May 1861 and “Colored Philadelphians Forming Regiment,” Weekly Anglo-African, May 4, 1861. For more, see Brian M. Taylor, “To Make the Union What It Ought to Be”: African Americans, Civil War Military Service and Citizenship (Doctoral Dissertation, 2015).

[4] “Meeting in Boston,” Weekly Anglo-African, May 4, 1861. For more, see Taylor, To Make the Union.

[5] “Meeting in Boston,” Weekly Anglo-African, May 4, 1861. For more on Brown, see Ezra Greenspan, William Wells Brown: An African American Life (New York: W.W. Norton, 2014).

[6] William Wells Brown, quoted in Nikki M. Taylor, “Negotiating Black Manhood Citizenship through Civil War Volunteerism and Patriotism: Cincinnati’s Black Brigade,” in Finkelman, Congress and the People’s Contest, pp. 224-36. For more, see Taylor, “Manhood Citizenship” and Taylor, To Make the Union.

[7] Frederick Douglass to Samuel J. May, August 30, 1861, Frederick Douglass Papers, Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus Libraries, University of Rochester, Rochester, N.Y.