The beginning of the war in Albemarle saw Black Virginians outnumbering the 12,103 Whites in the county. There were 13,916 slaves and 606 free people of color living in Albemarle in 1860. As thousands of White men left to serve in the Confederate military, African Americans increasingly represented a larger proportion of the population, leading to even harsher laws and regulations restricting their movements and livelihoods. As historian Ervin L. Jordan, Jr., notes, Black Virginians were consistently “disenfranchised, exploited, ostracized, and suppressed.” They were prohibited from independently practicing religion, and many were forced into carrying out labor for the Confederate military. The precarious legal status of free Black Virginians continued into the Civil War years, in many cases worsening, as White Albemarle natives increasingly saw them as a potential threat to their Confederate cause. Slaves, too, faced stricter regulation, including a newly implemented nine o’clock curfew. White Virginians across the state were vigilantly watching for signs of Black insurrection, terrified that the war would bring about rebellion and prepared to respond viciously wherever that was the case.

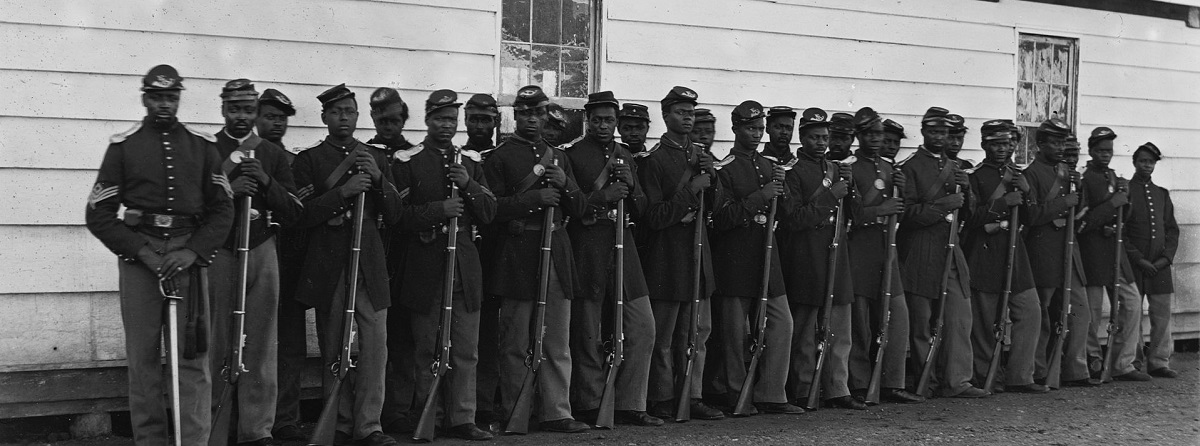

Amid this turmoil, many Black Virginians began enlisting in the Union military. Geographically spread throughout the country—either of their own volition or because of the slave trade—these men found their way to recruiting stations across the United States or Union-occupied areas to fight against the Confederate cause.

African Americans were initially admitted into the Union army solely to carry out manual labor. As historian William Dobak notes, though, contrary to the initial intentions of the president and Congress, “black soldiers’ service included every kind of operation that Union armies undertook during the war: offensive and defensive battles, sieges, riverine and coastal expeditions, and cavalry raids.” Some men from Albemarle County had extensive combat records, participating in numerous operations with their regiments.

On land, about 179,000 Black men served in what was known as the United States Colored Troops, or USCT for short. About 5,700 Black soldiers enlisted in regiments raised in Virginia, although many thousands more who were born in the state enlisted elsewhere as fewer than 20 of the 260 soldiers and sailors who were born in Albemarle actually joined the USCT in their home state. At sea or in navigable rivers, 18,000 Black men served in the Union navy, over 2,800 of whom were born in Virginia.

The Nau Center currently knows of 260 Union soldiers and sailors that were born in Albemarle County. The majority of these men served in infantry regiments of the USCT, but several also mustered into cavalry, artillery, and engineer units. Six of these men served in the Union navy. The first Black man from Albemarle to enlist in either armed service was Landsman Alexander Caine, who joined the Union navy in January 1862, serving on board the USS St. Louis cruising for Confederate privateers or blockading southern ports until his discharge in early 1865.

Three of the first Albemarle-born African Americans to enlist in the army did so in Louisiana, where Black regiments mustered into the Union army beginning in 1862. Called the Louisiana Native Guards, these early regiments appointed primarily Black officers and were comprised of a mix of runaway slaves and free people of color. Miles Lucius and Stephan Washington enlisted in the 3rd Louisiana Native Guards at the regiment’s inception on November 24, 1862. Horace Washington joined the 4th Louisiana Native Guards a few months later in February 1863. Including these men, there were at least ten Black Virginians who made their way to Louisiana in the years before and during the war and enlisted in the Union military. As the war progressed, their unit designations changed from the Louisiana Native Guards to the Corps d’Afrique and, finally, to the standard USCT.

Many Black Union soldiers were runaway slaves, who had escaped in the years before or during the war. This was the case for numerous USCT men from Albemarle County. William Page, for example, was born in Norfolk in 1839 and enslaved in Blenheim, Albemarle County. He was owned by Andrew Stevenson, a former member of the Virginia House of Delegates who also served on the University of Virginia’s Board of Visitors and as the University’s rector from 1856-1857. Page lived and worked as a waiter on Stevenson’s estate, but at some point before 1864 he escaped to Baltimore, Maryland, where he enlisted in the 39th USCT Infantry Regiment. Page was present with his regiment for the Overland Campaign in Virginia in May and June 1864, the Siege of Petersburg from June to October, and expeditions into North Carolina which included the Bombardment of Fort Fisher and the Battle of Sugar Loaf, both in January 1865.

Henry Kettel, too, was enslaved about 13 miles outside of Charlottesville for much of his life. As a young man, Kettel ran away with his brother, Edmund Williams, and settled in Washington, D.C. There, they would both enlist in the Union army in 1864, Kettell in the USCT and Williams in the Quartermaster’s Department. In Missouri, the Carter family (John Coles Carter, Sr. and Jr.) slaves left in droves from their masters’ plantations in Pike and Lincoln counties. Between 1863 and the end of the war, twenty-five Carter men made their way to Union recruiting stations across Missouri, where they joined the 18th, 62nd, 65th, 67th, and 68th USCT Infantry Regiments.

Peter Churchwell, who was enslaved on a plantation in nearby Orange, Virginia, for much of his life, had escaped and gained his freedom in Washington, D.C. by 1862. He enlisted in the 23rd USCT. Infantry Regiment there on July 13, 1864. Soon after enlisting, Churchwell participated in the disastrous Battle of the Crater in late July, where he was badly wounded and captured by Confederate soldiers. After forcing him and other captured Black soldiers to dig graves for several days, Confederate authorities returned Churchwell to his pre-war owner. Though he would go on to escape again, his experience highlights the very real threat of re-enslavement that freed and escaped Black Americans faced when serving in the Union military. As noted by historian Earl J. Hess, “there seems to be no final accounting of the number of Union soldiers who thus returned to slavery,” but there were several recorded incidents, including Churchwell, from the Battle of the Crater alone.

Numerous free Albemarle-born African Americans enlisted in the army as well. Wilson Miles Evans, for example, was born in Charlottesville and enlisted in the 16th Infantry Regiment of the USCT in Ohio, where he lived as a free man in 1864. In December 1864 Evans took part in the Battle of Nashville with his regiment, as the looming threat of Confederate General John Bell Hood’s army moved nearer. Around the same time, Albemarle-born brothers John and James Battles—both members of the 102nd USCT Infantry Regiment—joined the USCT from their home of Niles, Michigan, just north of the Indiana border. Stationed in South Carolina in late 1864, the Battles brothers fought in the Battle of Honey Hill on November 30, where their regiment was assigned to retrieving the guns of the 3rd New York Artillery while taking heavy Confederate fire. A Confederate victory with staggering Union casualties, the Battle of Honey Hill involved thousands of Black soldiers who were lauded for their bravery even in defeat.

Also present at this battle were the 54th and 55th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiments. The 54th Massachusetts was already well known for the bravery of its Black soldiers, after they fought valiantly at the Battle of Fort Wagner. James Davenport, born in Albemarle County, enlisted in the 54th Massachusetts in December 1863, several months after this famous battle and served as the company cook. Several men from Albemarle also enlisted in the 55th Massachusetts, the lesser-known sister regiment to the 54th, including brothers Manuel and Alexander Jackson. Manuel and Alexander were born slaves in Albemarle but were freed sometime before 1854, after which they moved with their parents to Ohio. Like many free people of color, they joined the Union army in Massachusetts, as it was the first free state to raise entirely Black regiments. They both enlisted on June 5, 1863, and saw numerous operations in Florida and South Carolina before participating in the Battle of Honey Hill.

Many of the men who were freed and moved out of state by their owners before the war also went on to enlist in the Union army. John Reed, who was freed and moved to Ohio as a child, enlisted in the 27th USCT Infantry Regiment on March 3, 1864, in Morrow Count, Ohio. Three men living in “Pandenarium,” the Pennsylvania settlement set up for the 63 former slaves of Dr. Charles Everett, also enlisted. John Allen, James H. Garland, and George W. Lewis enlisted in Company A of the 127th USC. Infantry Regiment in Philadelphia in August 1864.

The decision to enlist in the Union military was not one to be taken lightly by Black men, as they faced the threat of re-enslavement and were often subjected to laborious tasks or unhealthy climates that contributed to diseases killing them in proportionally higher numbers than their White comrades. Even though many USCT units were stationed behind Union lines or did not participate in as many battles as White regiments raised in 1861, 18.5% of all Black soldiers died in the service. The mortality rates for Albemarle County men was even higher: 28% or 72 out of 260 who enlisted. Of these fatalities, 66 occurred from disease, one from an accident, and only five from battle wounds. The leading killers for Albemarle Black men and their Black comrades from other places included diarrhea, dysentery, pneumonia, and small pox. As their pension records attest, even those who survived suffered lingering health issues from wounds received, diseases contracted, or backbreaking labor that hurt their ability to provide for themselves or their families long after the war. Private Henry Armstrong, for example, listed rheumatism, heart disease, and vertigo resulting from a sabre blow to the head at the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm in September 1864 in his pension application filed in the 1890s.

Back home in Albemarle, many African Americans were forced into service in the Confederate military. Throughout the course of the war, numerous free and enslaved Black Virginians were coerced into Rebel service with a series of progressively demanding state and Confederate impressment laws. Virginia lawmakers passed the first impressment act in February 1862, which stated that all free people of color between the ages of eighteen and fifty had to report for noncombatant Confederate service. After this measure still did not produce enough laborers, the legislature passed another law in October to begin seizing slaves. Met with vehement protests from both slaves and owners, this legislation and a subsequent Confederate law implemented strict quotas for slave impressment from each Virginia county. According to Ervin Jordan, between the years 1862 and 1864 around 940 Albemarle County slaves were forced to perform labor for the Confederacy.

Black Virginians also worked in the Charlottesville General Hospital, some voluntarily but most upon conscription. The hospital, which the University of Virginia set up to treat wounded and sick soldiers, opened in 1861. Many Black women worked in the hospital as nurses. They were paid twenty dollars a month for this position in 1861 and were afforded housing and rations. Most of the vital day-to-day operations of the hospital were carried out by Black workers, including feeding and bathing patients, digging graves, and repairing hospital facilities, which were spread across various buildings in town. Still, as Ervin Jordan writes, they were largely ignored by their White coworkers as “invisible inferiors.” Many resented and resisted their Confederate impressment, deserting their positions when given the chance.

Religion was central to the lives of Black Virginians during this time. As noted by historian and minister Richard I. McKinney, an 1832 state law prevented African Americans from holding their own religious ceremonies without the presence of at least one White supervisor or preacher. This led to them joining White churches, where they were treated as secondary members of the congregations, often relegated to segregated balconies and stripped of any stake in the organizations. This was the case for the Charlottesville Baptist Church, which had approximately 800 Black congregants in the early 1860s. The Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, while not sufficient in actually liberating most Albemarle slaves from their masters, stoked the desire for freedom in many Black members of the community. Two months after the Proclamation, they applied to the church to form their own separate organization. Though the drawn-out process wound through committee meetings, tedious reports, and a conference of Black community leaders, Black Albemarle natives succeeded in establishing the church by the following summer of 1864. The organization would come to be known as First Baptist Church of Charlottesville, and in its formation Black Virginians made clear their will and capability for self-determination.

As the war progressed further into 1864, Confederate confidence about a short, low-casualty conflict was shaken. Union victories were increasing in numbers and some, like the Siege of Port Hudson and the Battle of Milliken’s Bend, succeeded with notable contributions from Black soldiers. This turning side soon threatened Charlottesville. In late February 1864, Union forces carried out the Kilpatrick-Dahlgren Raid on Richmond, and General George A. Custer moved troops into Charlottesville in an attempt to split Confederate defenses. Union soldiers attacked the Stuart Horse Artillery Battalion, destroying the camp and its supplies but ultimately failing to claim decisive victory. The conflict became known among locals as the Battle of Rio Hill, with Federal forces retreating before they could seriously threaten Charlottesville or occupy Albemarle County.

A little over a year later, Union forces returned to Charlottesville. As Jordan notes, this time they arrived with the momentum of the recent victory at the Third Battle of Waynesboro on March 2, 1865. In an effort to protect the town and university, Charlottesville officials surrendered to Union Generals Philip H. Sheridan and George Custer on March 3. During the subsequent occupation, which lasted three days, members of the community reported that many slaves assisted Union forces as they raided the city. John B. Minor, a professor at the University of Virginia, wrote in his diary that “several of [Colonel Thomas L. Preston’s] servant boys have gone off and have betrayed all his horses to the enemy.” He also noted reports that numerous slaves fled their masters and left with Union troops, including his own servant, Henry.

With this surrender, Albemarle became one of hundreds of southern counties on the precipice of massive societal change. Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox a month later solidified this feeling, and though for many White southerners it was one of defeat, for African Americans throughout the North and South it was one of intense hope and possibility. Still, the emancipation promised by the end of the war was not immediate, and it took a post-Appomattox Union occupation of Albemarle to start to enforce an end to slavery in the county. As Ervin Jordan writes, it took time to negotiate the “social and economic readjustments” between White and Black Virginians, and there were several instances of ex-slaves suing their former owners, and vice versa. The states did not ratify the 13th Amendment, officially abolishing slavery in December 1865. When they finally did gain their freedom, Black Virginians faced many challenges — pervasive racism across the newly reunified country would persist well through the period of reconstruction. But the end of the war set Albemarle County squarely on the path toward a new way of life, shaped by the recognition of Black Virginians as free and full members of the community.

Image: Men of the 4th USCT Infantry Regiment (courtesy Library of Congress).

Compiled Service Records for Peter Churchwell, Nimrod Eaves, Henry Kettell, William Page, John Reed, and James T.S. Taylor, RG 94, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Accessed through Fold3 (https://www.fold3.com/browse/273/); Pension records for Peter Churchwell, Thornton Davis, Nimrod Eaves, Henry Kettell, William Page, John Reed, and James T.S. Taylor, RG 15, National Archives and Records Administration; William A. Dobak, Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops 1862-1867, (Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, 2011); Douglas R. Egerton, Thunder at the Gates, (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2016); Ervin L. Jordan, Jr., Black Confederates and Afro-Yankees in Civil War Virginia, (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1995); Earl J. Hess, Into the Crater: The Mine Attack at Petersburg, (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2010); Ervin L. Jordan, Jr., Charlottesville and the University of Virginia in the Civil War, (Lynchburg: H. E. Howard, Inc., 1988); Richard I. McKinney, Keeping the Faith: A History of The First Baptist Church, 1863-1980, (Charlottesville: First Baptist Church, West Main Street, 1981); John B. Minor, Diary of John B. Minor (February 28–March 7, 1865), Diary, From Encyclopedia Virginia, https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Diary_of_John_B_Minor_February_28-March_7_1865 (accessed May 1, 2019).