Following the disaster at the Crater in the summer of 1864, Lieut. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant planned for another offensive late in the following September. Grant ordered Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler to lead an attack towards Richmond north of the James River with the goals of taking the city and diverting Robert E. Lee’s forces away from Petersburg. Grant told Butler, “The prize sought is either Richmond or Petersburg, or a position which will secure the fall of the latter.” Butler’s ensuing two-pronged offensive would result in the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm, also referred to as the Battle of New Market Heights, on September 29 and 30. Although not discussed much today, historian Douglas Crenshaw writes that in the victories at Chaffin’s Farm “the Union came closer to capturing Richmond than at any other time during the war,” potentially saving thousands of lives. Yet, the site of the battle remains, as described by National Park Service historian Mike Gorman, “one of the most important unpreserved battlefields around the Richmond area.” Despite United States Colored Troops (USCT) soldiers receiving fourteen of the twenty-five Medals of Honor that Black troops earned during the entire Civil War at Chaffin’s Farm, their bravery and heroism is likewise not well known.

USCT troops from Maj. Gen. David B. Birney’s Tenth Corps and Maj. Gen. Edward O. C. Ord’s Eighteenth Corps were present at Chaffin’s Farm. The Tenth Corps’ Third Division contained Brig. Gen. William Birney’s brigade, of which the 29th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry Regiment (Colored) and the 7th, 8th, 9th, and 45th USCT were a part. The Eighteenth Corps’ Third Division, under Brig. Gen. Charles J. Paine, contained three brigades of USCT regiments. The 1st Brigade under Brig. Gen. Henry Holman had men of the 1st, 22nd, and 37th USCT Infantry Regiments. Under Col. Alonzo G. Draper, the 2nd Brigade contained soldiers of the 5th, 36th, and 38th USCT Infantry Regiments. Col. Samuel A. Duncan’s 3rd Brigade consisted of the 4th and 6th USCT Infantry Regiments. Additionally, the 2nd USCT Cavalry Regiment was present although in an unattached capacity.

As many as eighteen USCT soldiers from Albemarle County were at the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm. These men included John Hailstock, Nelson Means, and Thomas Walker of the 1st USCT; Charles Rollins, Joseph H. Thomas, and John M. Winfrey of the 4th USCT; Miles Carr, William Evans, John N. Farrow, Thomas Gibson, William O. Gibson, James M. Goings, Nimrod Goins, Isaiah Reed, and Edward Rollins of the 5th USCT; Henry Armstrong of the 38th USCT; Edward Patterson of the 45th USCT; and Jesse Sumner Cowles of the 29th Connecticut. Two men received wounds at Chaffin’s Farm or nearby action: Edward Rollins at Fort Gilmer and Henry Armstrong with a sabre blow to the head at Deep Bottom. Three men perished in the battle: John N. Farrow at Fort Harrison, William Evans at New Market Heights, and Miles Carr at Deep Bottom, all on September 29. All three of these men were in the 5th USCT, which took heavy casualties that day. Of the more than two hundred and fifty men identified by our Black Virginians in Blue project only five were killed in combat, making the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm by far the deadliest fight of the war for Albemarle Black soldiers.

This blog will highlight the lives of four Black Virginians in blue: Henry Armstrong, Joseph H. Thomas, Nimrod Goins, and Isaiah Reed. Henry Armstrong was born in Albemarle County, Virginia, around 1834. He enlisted and mustered into the Union Army at the age of 30 as a private on July 30, 1864, in Norfolk, Virginia, for a period of three years. At the time of his enlistment, he stood at 5 feet 4 inches with black hair and eyes coupled with a "dark" complexion and gave his occupation as "fisherman" and "farmer." Armstrong served in company G of the 38th USCT and performed the task of company cook.

Joseph H. Thomas was born around 1836 in Albemarle County. Thomas spent most of his childhood as a freeman living in Ross County, Ohio. According to his service record, at the time of his enlistment he stood at 5 feet 7 inches, with blue eyes, light hair, and a light complexion. Census records listed him as a mulatto and show that he lived in his older brother John’s household and worked as a farmer on the farms of James M. Shriver, Jr., of Union Township. According to his pension, he decided to answer “Old Uncle Abe’s” call for another half a million more volunteers in 1864 as he was “anxious to see some Johnnies.” Thomas enlisted as a private in Company K of the 4th USCT in Chillicothe, Ohio, on September 2, 1864, and mustered into service the next day in Circleville.

Nimrod Goins was born August 10, 1836, in Albemarle County. Prior to the war, he lived in Amesville, Athens County, Ohio, working as a laborer and married his first wife Eliza (Lizette) Rogers on August 18, 1861. The pair had eleven children, including Josephine Williams and Albert Goins. Goins enlisted at the age of 28 as a private on August 10, 1864, and mustered in on the next day in Marietta, Ohio. His service record describes him as 5 feet 8 inches, with black hair, black eyes, and dark complexion. Goins served in Company G of the 5th USCT.

Isaiah Reed was born February 12, 1840, in Howardsville, Albemarle County, Virginia. Prior to enlisting, Reed lived in or near Buchanan, Pike County, Ohio, where he did "ordinary farm work" on the farm of the father of James M. Dolahan, according to his pension. Reed enlisted and mustered into the Union army as a private at the age of 23 on June 15, 1863, at Washington Court House, Ohio. At the time of his enlistment, the 23-year-old freedman stood 5 feet 9 inches, with black hair, eyes, and skin complexion. Reed enlisted for a period of 3 years, and served as a private in Company A of the 5th USCT.

In the early morning of September 29, Maj. Gen. David B. Birney took his troops of the Tenth Corps and several regiments from the Eighteenth Corps, one of the two prongs of Butler’s assault, across the James River to attack the Confederate works at New Market Heights. After successfully skirmishing with Rebel outposts, the Corps moved towards the New Market line. As the Corps advanced, Paine blundered by not pushing far enough west, leading to terribly high casualties due to attacking more difficult obstacles he should have bypassed. Paine ordered Duncan to attack the New Market Line with his brigade, using the 4th USCT with the 6th and 10th USCT as support. Duncan’s men faced terrible resistance due to multiple stages of obstacles including a mess of felled trees, earthworks, well as chevaux-de-frise. To motivate his men, Butler told them: “Your cry, when you charge, will be, ‘Remember Fort Pillow,” the site of a terrible massacre of USCT soldiers by Rebel forces under Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest earlier that year.

Duncan’s assault met with frightening opposition. Col. Joseph Hiram Goulding of the 6th USCT wrote of the battle: “The air seems full of missiles, hissing above, around and with deadly intent at each one of us. Man after man with the colors goes down, and officer after officer as they snatch the falling staff from stricken arms.” Many color bearers perished in the assault, with other soldiers picking up the flags resulting in some of them winning Medals of Honor. African American Sgt. Maj. Christian Fleetwood of the 4th USCT later wrote of the retreat following the failed assault, “Reaching the line of our reserves and no commissioned officer being in sight, I rallied the survivors around the flag, rounding up at first eighty-five men and three commissioned officers.” Compounding the terrible losses was a failure by Brig. Gen. Alfred C. Terry to support Duncan’s assault, another example of poor leadership resulting in high costs to the USCT men. Of the nearly seven hundred and fifty men of Duncan’s Brigade who first assaulted the New Market line, three hundred and eighty-seven were killed or captured, with the 6th USCT losing over half of its strength. Cpl. Joseph O. Cross of the 29th Connecticut later described it as “a hell, the horrors of which no one could ever forget.”

Around the same time as Birney lead the attack on the New Market Line, Ord took the remaining men of the Twenty-third Corps, his prong of Butler’s assault, across the James against Fort Harrison. Although, Ord’s forces were at this point predominantly White, some soldiers of Black regiments, including the 8th USCT, were present at the assault. Brig. Gen. George Stannard led Ord’s attack on Fort Harrison, charging across an open field to make it to the fort. One soldier recalled thinking “the prospect is terrible” and that the attack “must be done quickly” in order to succeed. Despite taking some losses, including eight officers and five hundred and fifty enlisted men, Stannard’s assault succeeded in taking the Fort. Gen. Hiram Burnham was killed in the attack and the Union army later renamed the fort in his honor. Inexperience and poor leadership would prove costly yet again, as rather than following the plan to immediately move on to Forts Gilmer and Gregg, Ord’s forces hesitated at Fort Harrison. Thus the Union may have missed a potential opportunity to march straight on to Richmond, which lay relatively undefended at the time due to Lee spreading his forces thin. Historian Mike Gorman claims that had the Eighteenth Corps managed to complete its mission, Butler’s forces could have marched up New Market road, following the Tenth Corps’ success at New Market Heights, and taken a relatively undefended Richmond to end the war.

Regardless of the strategic blunders following the success at Fort Harrison, the result forced Brig. Gen. John Gregg to divert forces from New Market Heights to defend Fort Harrison. This movement coincided with the second assault on the New Market Line, which proved fortuitous for the Union troops. Minutes after Duncan failed to take the Heights, Birney ordered another attack, this time under Draper. Lt. Col. Giles Shurtleff of the 5th USCT stood before his men prior to the assault, claiming that if they performed as “brave soldiers, the stigma…denying you full and equal rights of citizenship shall…be swept away and your race forever rescued from the cruel prejudice and oppression which have been upon you from the foundation of the government.” As the attack began, the brigade began to make the same mistake as Duncan’s assault, in which they were attacking an entrenched enemy. After about thirty minutes, Draper managed to get his officers to rally their men, cease firing, and charge the Confederate lines.

Despite taking heavy losses, Draper’s assault managed to swarm the Rebel entrenchments. Pvt. James Gardiner managed to shoot a Rebel officer, inspiring his comrades and later earning him the Medal of Honor. The attack succeeded, resulting in the Rebel forces retreating towards Fort Harrison in, what Confederate clerk Charles Crossland later described as a “panic.” One soldier of the 38th USCT described his experiences later in his life:

“I fit…wid de ole 38th regiment. We had colored sojers an’ white officers. We licked de ‘federate good an’ made ‘em [retreat] up to a place called Chaff’s farm. Never will I fergit dat battle. It come on a Thursday, Sept. 29, 1864.”

Butler, additionally, gave great respect to the USCT soldiers’ service at New Market Heights:

“[Paine’s colored troops] suffered largely and some two hundred of them lay with their backs to the earth and their feet to the fore, with their sable faces made by death a ghastly tawny blue, with their expression of determination, which never dies out of brave men’s faces who die instantly in a charge, forming a sad sight, which is burnt on my memory…Poor fellows, they seem to have so little to fight for in this contest, with the weight of prejudice loaded upon them, their lives given to a country which has given them not yet justice, not to say fostering care…But there is one boon they love to fight for, freedom for themselves and their race forever, and “may my right forget her cunning” but they shall have that. The man who says the negro will not fight is a coward…His soul is blacker than the faces of these dead negroes, upturned to heaven in solemn protest against him and his prejudices… I have not been so much moved during this war as I was by that sight.”

Draper’s brigade took terrible casualties in order to succeed at New Market Heights. Of the thirteen hundred men who assaulted the Heights, Draper lost more than four hundred. The 5th USCT alone had over two hundred men killed, captured, wounded, or missing.

Following the success at Fort Harrison and New Market Heights, Butler’s troops tried to continue on and take Fort Gilmer. Brig. Gen. Robert Sanford Foster first attempted to assault Fort Gilmer following the victory at Fort Harrison but failed, taking heavy casualties. Foster attempted another assault, this time using me from Paine’s Third Division, once again putting the 5th USCT into battle. The attack order from Birney was futile with the officer leading the skirmish line exclaiming, “What! Take a fort with a skirmish line? Who ever heard of such a thing? I will try, but it can’t be done.” The attack failed terribly, with only a single man of the one hundred and twenty soldiers of the 7th USCT escaping from death, wounds, or capture. Once again, as noted by historian William Dobak, an unfortunate “lack of coordination” at Fort Gilmer as in earlier attacks elsewhere that morning doomed Union efforts. The following day, on September 30, Lee attempted to retake Fort Harrison. Though Lee diverted 10,000 reinforcements from Petersburg his counterattack failed with heavy Rebel casualties.

Shortly after the battle, many recognized the dutiful service of the USCT at Chaffin’s Farm and the importance of their accomplishments. A Tenth Corps surgeon wrote that day: “I dressed the wounds of twelve colored men belonging to the Eighteenth Corps. They fought splendidly and I took great satisfaction in doing for them.” Black journalist Thomas Morris Chester wrote that the USCT men had “covered [themselves] with glory, and wiped out effectually the imputation against the fighting qualities of the colored troops.” Even Lee recognized the magnitude of the victory, telling one of his generals expecting a quick victorious reprisal, “I made my effort this morning and failed, losing many men killed and wounded. I have another line provided for that point and shall have no more bloodshed at the fort unless you can show me a practical plan of capture; perhaps you can. I shall be glad to have it.” After the war, a Rebel veteran wrote that Chaffin’s Farm marked the time that “Richmond came nearer being captured, and that, too, by negro troops, than it ever did during the war.”

Nineteenth-century African American writers also recognized the importance of the battle for the USCT’s overall reputation. Two years after the war, prominent Black abolitionist and author William Wells Brown praised the Black soldiers at the battle for having “nobly sustained their reputation gained on other fields,” which was particularly important in the wake of the Union’s failure at the Crater earlier in July. Similarly, USCT veteran and historian Joseph T. Wilson praised Black troops at Chaffin’s Farm in his book The Black Phalanx, noting their White northern critics “could croak no longer about the negro soldiers not fighting.” Wilson reprinted a long poem titled “New Market Heights” whose author over the course of eighteen stanzas attempted to “essay their deeds of valor done, by which the nation its victory won.”

Historical disagreement over the importance of Chaffin’s Farm has contributed to why it has remained a relatively unknown battle. In recent literature, some historians have claimed that Butler oversold the victory at New Market Heights. Richard J. Sommers writes that Butler “trumpeted” the legend of a great victory for the rest of his life, despite Duncan taking a “virtually abandoned position.” Noah Trudeau alleges that despite heroism and sacrifice, the “ultimate justification for the fighting at New Market Heights was neither tactical nor strategic but political.” Additionally, Barry Popchock called New Market Heights “less than the glorious victory that the self-serving Butler proclaimed,” claiming the USCT advance only succeeded because Gregg pulled his troops to combat the Union victory at Fort Harrison. However, other historians dispute these claims. Versalle F. Washington noted that Gregg pulled his men away towards Fort Harrison, “once it became clear they would not be able to hold New Market Heights.” Douglas Crenshaw additionally supports this claim, explaining that while it is plausible that the USCT advanced as Gregg pulled out, it does not diminish the “incredible bravery” they displayed at New Market Heights.

While history may not have remembered the service of the veterans of Chaffin’s Farm, many contemporaries across the country or in the government or military paid them some respect for their service within their lifetimes following the war. The military awarded fourteen Medals of Honor to USCT soldiers, by far more than in any other action of the war. Some of the men received their medals as early as April 1865 making them “the first black soldiers to be honored with a military decoration” in the entire war according to historian William Dobak.

Dissatisfied with a lack of recognition for his Black troops, Butler designed his own medal with the motto ferro iis libertas, which translates to “freedom by the sword,” and gave it to nearly two hundred of his soldiers. This episode marks one of the rare times a White officer so rewarded his Black troops in the Civil War. Butler never forgot the service of his troops during the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm, ordering that each regiment who was at New Market Heights to inscribe it on their regimental colors. Additionally, Butler referenced their heroism later as a congressman arguing for the Civil Rights Act of 1874. Although at a much lower rate and with much more difficulty than their White counterparts, many USCT veterans received government benefits such as federally supported veterans’ homes and pensions. Many of them joined veterans’ organizations like the Grand Army of the Republic, where some of their fellow White soldiers and officers remembered their meritorious service. Altogether, following the war the surviving Black Virginians in blue and their fellow USCT veterans tried to move on with their lives as best as they could, having secured freedom but not full equality.

Henry Armstrong returned to Virginia, living in Norfolk and later Gloucester County. He married Lucinda Jarley on August 2, 1868, and had a single surviving child--Robert--born May 31, 1869. In 1890, a Dr. James P. Weight confirmed the sabre blow Armstrong received at Deep Bottom, which the doctor claimed rendered Armstrong "almost totally incapacitated for manual labor." He began receiving a pension of $10 a month in 1891 that the War Department reduced to $6 a month in 1895 due to discrepancies between the pension records and the requirements of the 1890 Act. In 1895, a doctor diagnosed Armstrong with vertigo as a result of the sabre cut, but another doctor in 1897 declared Armstrong's scar superficial and not enough to cause brain damage. His condition worsened until his death on November 12, 1899, in Gloucester, of unknown causes. His widow Lucinda unsuccessfully applied for a pension, hindered by insufficient records.

Joseph H. Thomas immediately returned to his brother’s home in Ohio until at least 1870. Although he attempted to work as a farm laborer, his health ailments continued to plague him. Thomas successfully applied for a pension in 1880, originally receiving $2 per month and receiving $12 a month by 1895. He died on March 13, 1895, on the Shriver Farm in Green Township. Thomas was not forgotten after his death. At his funeral in a Green Township chapel, the local African Methodist Episcopal choir sang, while members of the local Black post of the Grand Army of the Republic served as pallbearers. Decades later, in 1932, a woman named Katie Thomas filed a pension application, claiming to be Thomas’s widow. Without any corroborating evidence or witnesses of their marriage, the pension office denied her claim.

Nimrod Goins returned to Athens Count, Ohio. His first wife died sometime before June 1898, and he subsequently married Lucy Gibson on October 10, 1906. Goins suffered from measles, lumbago, rheumatism, lung and heart disease, and disease of the stomach in addition to a declining mental condition. In his pension records he claimed his second wife conspired with his first cousin, fellow 5th USCT veteran Thomas Gibson, to send him away to his daughter while they cohabited and collected his pension. It is unclear if this plot was true, but Goins did leave his wife on July 4, 1914, to go live with his daughter Josephine, who became his guardian, with Gibson and Lucy eventually living together. Goins’s mental condition deteriorated and he became violent and suicidal. He died of heart disease on January 26, 1916, in Athens.

Isaiah Reed also returned to Ohio, living first in Pike County, and later Clark County. According to his pension record, he married Amilia Bird on July 3, 1874, with whom he had four children. His pension only named three of his children: Lizzie E., Willie E., and Clarence. Although Reed suffered from cough, disease of the lungs, and "malarial poisoning," he was able to work as a farmer for a James A. Steele and became a member of the Grand Army of the Republic. Reed began filing for a pension in 1879 and was receiving one by 1890 that increased to $12 a month by 1906. He died of old age on June 23, 1910, in Springfield and is buried in a soldier's cemetery there. Following his death, his widow Amelia applied for a pension for herself and her minor child, but was unable to receive one.

The Union victory at Chaffin’s Farm on September 29 and 30, 1864, is important, both due to the strategic threat to Richmond and Rebel morale as well as the exceptional heroism that USCT soldiers displayed at the battle. Though contemporaries widely-recognized their bravery and valor, USCT veterans continued to face disproportionate adversity following their services. In more recent years, some efforts have been made better remember the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm, including a recent military history written by Douglas Crenshaw, public talks given by Mike Gorman, and attempts to preserve the battlefield and memorialize the soldiers who fought there. Whether the battle takes a more prominent place in the memorial landscape or Civil War literature, however, remains to be seen.

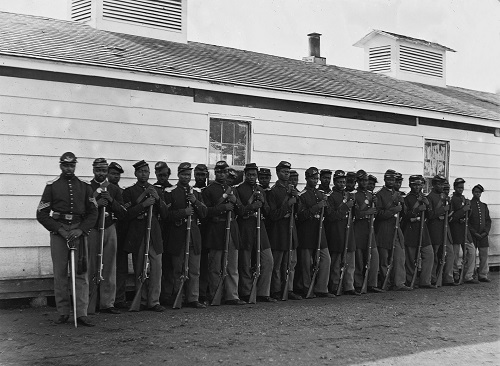

Images: (1) Men of the 4th USCT Regiment; (2) Map of the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm; (3) A Bombproof at Fort Burnham; (4) Union Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler; (5) Fort Burnham with Fort Beauregard in the Distance (all images courtesy Library of Congress).

Compiled Service Records for Henry Armstrong, Miles Carr, Jesse Cowles, William Evans, John N. Farrow, Thomas Gibson, William O. Gibson, James M. Goings, Nimrod Goins, John Hailstock, Nelson Means, Edward Patterson, Isaiah Reed, Charles Rollins, Edward Rollins, Joseph H. Thomas, Thomas Walker, John M. Winfrey, RG 94, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; Pension records for Henry Armstrong, Miles Carr, William Evans, John N. Farrow, Nimrod Goins, Isaiah Reed, Edward Rollins Joseph H. Thomas, RG 15, National Archives and Records Administration; Charles R. Bowery Jr. and Ethan S. Rafuse, Guide to the Richmond-Petersburg Campaign, (Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2014); Douglas Crenshaw, Fort Harrison and the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm: To Surprise and Capture Richmond, (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2013); William A. Dobak, Freedom By the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops 1862-1867, (Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, 2011); Frederick A. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion, vol. 3 (New York: T. Yoseloff, 1959); James S. Price, The Battle of New Market Heights: Freedom Will Be Theirs By the Sword, (Charleston, S.C.: The History Press, 2011); Hampton Newsome, Richmond Must Fall: The Richmond-Petersburg Campaign, October 1964, (Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 2013); Richard J. Sommers, Richmond Redeemed: The Siege at Petersburg, (New York: Doubleday & Company, 1981); William Wells Brown, The Negro in the American Rebellion: His Heroism and Fidelity, ed. John David Smith (Boston: Lee & Shepherd, 1867; reprint, Athens: Ohio University Press, 2003); Joseph T. Wilson, The Black Phalanx: African American Soldiers in the War of Independence, the War of 1812, and the Civil War (Hartford, 1887; reprint, New York: De Capo Press, 1994); Mike Gorman, “New Market Heights: The Union Assault,” American Battlefield Trust, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uPy92WSgkVE.