In the late fall of 1864, Confederate General John Bell Hood led his defeated Army of Tennessee from the ruins of Atlanta. The city, a key logistical and supply center, had been leveled by Union forces under Major General William T. Sherman. As Hood retreated to lick his wounds west of the city, Confederate President Jefferson Davis ordered him to harass and weaken the enemy while avoiding a full-scale engagement. Hood was so successful in this endeavor that in a bold stroke, Sherman proposed to abandon his supply line and march across Georgia. The Army of Tennessee was powerless to stop the devastation of the Georgia countryside, and the aggressive Hood looked northward seeking to take back the initiative. Union forces in the state capital of Nashville, under the command of Major General George H. Thomas, represented a golden opportunity for an offensive operation. Yet it was also a tremendous gamble—Hood’s army was significantly outnumbered, and avenues for the Confederate high command to prolong the conflict were growing thinner by the day.

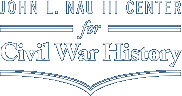

Thomas had approximately 50,000 troops under his command scattered throughout Tennessee and northern Alabama. Upon receiving news of Hood’s threat to Nashville, he began to concentrate his forces. Included in his reorganized Army of the Cumberland were approximately 8,000 troops under the command of Major General James B. Steedman detached from the District of the Etowah in eastern Tennessee. The division contained multiple United States Colored Troops (USCT) units, including nine soldiers originally hailing from Charlottesville or Albemarle County, Virginia. While Thomas strongly supported the government’s policy of recruiting African Americans, he had little confidence in their fighting abilities. A Virginian by birth, he was raised in Southampton County, Virginia, and had experienced Nat Turner’s slave rebellion in 1831. Thomas originally intended not to use the USCT troops under Steedman in the upcoming offensive. Nevertheless, he “promptly ordered that no distinctions should be made in this matter between Black and White troops” in the buildup to the campaign. The subsequent battle of Nashville would forever transform Thomas’s thinking surrounding the use of Black troops in combat, and offered a convincing argument for their continued usage.

The nine Albemarle men present in and around Nashville in December 1864 served in a variety of regiments, all under Steedman’s command. These men were James M. Barnett and Prince Bradford of the 17th USCT Infantry Regiment; Arthur Clayton of the 14th USCT Infantry Regiment; Wilson M. Evans and Henry Morse of the 16th USCT Infantry Regiment; James Gillum and William Tucker of the 18th USCT Infantry Regiment; Henry Graham of the 13th USCT Infantry Regiment; and Washington Randle of the 12th USCT Infantry Regiment. Often neglected by a traditional focus on Black troops serving in the Eastern Theater, serving in more famous engagements such as at Fort Wagner or in the battles around Petersburg, these western USCT soldiers played a critical role in one of the Union’s most important and complete victories anywhere during the Civil War. This essay will focus on the stories of Barnett, Bradford, Evans, and Gillum in order to explore their contributions to Union victory, the end of slavery, and the lasting impact of the conflict on the post-war lives of Black veterans and their families.

James M. Barnett was born around 1823 in Albemarle County. Sometime prior to the war, Barnett moved to Pike County, Ohio. He had one child, John W. Barnett, who was born on August 2, 1852, from his first wife who passed away in 1858. Barnett subsequently married Mary Ann Jackson and had two children with her: Sarah A., born on August 2, 1862, and James V., born on December 17, 1864.

Barnett enlisted as a private at the age of 41 on September 7, 1864, and mustered in on September 13, both in Dayton, Ohio. His service record describes him as 5 feet, 7 inches tall, with black hair, black eyes, and a black complexion. He served in Company I of the 17th USCT.

Another 17th USCT veteran was Prince Bradford, who was born around 1822 in Albemarle County. He was a slave of a Mr. Hamilton Bradford, who moved to Huntsville, Alabama, when Prince was ten years old. He worked as a blacksmith on the Bradford plantation. According to his pension testimony, he ran away from the Bradford plantation to enlist in the army.

Prince enlisted as a private at the age of 41 on November 20, 1863, in Alabama, and mustered in on December 12 in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. His service record describes him as 5 feet, 10 inches tall, with black hair, black eyes, and a black complexion. He served in Company A of the 17th USCT. Bradford was promoted to corporal on February 29, 1864, a rank he would retain until the war’s conclusion. During the conflict, Bradford was an active member of the 17th USCT, who mainly saw action in East and Middle Tennessee. The 17th USCT would soon prove critical to Thomas’s victory.

Wilson Miles Evans was born around 1836 in Albemarle County, but little is known of his early life except that he had lived in Highland County, Ohio, prior to joining the army. It was here that he married his wife, Mary Skipworth Evans, on October 30, 1856.

He enlisted as a free man in the 44th USCT Infantry Regiment on September 15, 1864, for a period of one year. However, his name was not taken up on the muster rolls of the 44th USCT, and he subsequently mustered into Company D of the 16th USCT as a private on the same day in Hillsboro. At the time of his enlistment, he was 28 years old, and stood 6 feet tall, with a yellow complexion, black eyes, and black hair. The regiment was serving in Chattanooga, Tennessee, until November 1864, when they were recalled back to Nashville as a result of Hood’s looming threat.

James Gillum (Gillam) was born on June 4, 1826, in Albemarle County. With land limited as the population increased, many children not due to inherit property titles sought their fortunes in the West, resulting in a high concentration of Albemarle and Charlottesville natives moving to Missouri’s Little Dixie region before the Civil War. Gillum was owned by a Mr. Nathan S. Gillum of Pike County, Missouri, for whom he worked as a farmer and teamster. At some point, he married an unnamed woman who died in 1866, with whom he had a child whose name is not known.

Gillum enlisted at the age of 38 as a private on August 30, 1864, in Bowling Green, Missouri, and mustered in the same day at Benton Barracks in St. Louis. His service record describes him as 5 feet, 8 1/2 inches tall, with crisp hair, black eyes, and a black complexion. He served first in Company I of the 18th USCT, but later transferred to Company F. Before the Franklin-Nashville campaign, he was promoted to the rank of first sergeant on October 10, 1864. He would later receive promotions to commissary sergeant on October 6, 1865, and quartermaster sergeant on November 10, suggesting a talent for coordinating the dispersal of equipment and munitions. With the 18th USCT, Gillum served throughout Tennessee during the war, including at Nashville.

As Hood pushed into Middle Tennessee, his troops suffered significant casualties, especially at the Battle of Franklin on November 30, 1864. Outnumbered nearly two-to-one, Hood decided against a foolhardy attack on the strong seven-mile-front of Union breastworks surrounding Nashville, and dug in on their eastern flank. Despite the weak nature of the Confederate force, US commanders responded with alarm. Believing that Hood’s force posed a significant threat to a subsequent invasion of Kentucky, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, commanding all actively engaged Union forces, pressured Thomas to move. For two weeks, Thomas stalled, citing bad weather and insufficient reconnaissance efforts. Yet on December 15, he ordered Steedman’s division, consisting mainly of USCT units, to launch a diversionary attack on the Confederate right flank, while the main attack moved into position on the Union right.

The USCT troops were originally assigned a passive role in the attack, a sign of Thomas’s distrust of their ability. Steedman had been able to convince Thomas that a limited attack on the Confederate right would deprive the enemy from transferring troops to meet other engaged forces. He led his troops into combat at 6:00 a.m., and successfully tied down Confederate units from moving to support the impending attack on Hood’s redoubts on the southern left. Steedman boasted that he had “pressed [the enemy’s] right strongly” in a note to Thomas. That evening, Steedman proudly gave Thomas an inaccurate report stating that his division had captured one portion of the Confederate breastworks while sustaining only 250 casualties. In reality, despite orders to only launch a limited attack, Steedman had ordered a major assault, sending his men directly into a trap.

The right flank of the Confederate line was quite formidable that morning—the Confederates had cleverly placed an artillery battery at a point in the line where it could enfilade a railroad cut. When Steedman’s men arrived to crowd the ravine, the battery opened fire and unleashed havoc. After-action reports indicate that while a brigade of White soldiers quickly retreated against this cannon burst, Steedman’s Black troops attempted courageously to move forward in the face of overwhelming force. They were pushed back at a tremendous loss, and Hood was thus able to transfer some troops to reinforce his faltering left later in the day. Thomas never learned the truth about Steedman’s attack, commending Steedman’s advance met with “great success and some loss” in his after-action report.

Despite success on his right, Hood was overwhelmed that afternoon, and the exhausted Army of Tennessee was left no choice but to retreat. They fell back two miles to a new line, where they dug in and awaited the Union advance.

While the USCT soldiers from Albemarle were engaged on the December 15, their main actions in the battle of Nashville would come the following day. Thomas spent most of the morning of the 16th moving his troops into position to attack the new Southern line. Centered around Shy’s Hill to the west and Overton’s Hill to the east, it was a commanding position. Overton’s Hill, also known as Peach Orchard Hill, derived its name from being used as a peach orchard on the property of John Overton, of nearby Traveler’s Rest. Two thousand troops under the command of Lieutenant General Stephen D. Lee’s Corps opposed the awaiting Union troops. More than 12,000 U.S. infantry concentrated for an assault that afternoon, while a two-hour artillery barrage ensued. Steedman’s division advanced forward at approximately 3:00 p.m., where they quickly became entangled in fallen tree tops that had been erected to slow their advance. As Union troops struggled to get through, Confederate artillery opened fire, and the infantry unloaded on the exposed troops. Overwhelmed, many of the Union troops broke and ran; however, many of the USCT units attempted valiantly to fight on.

Under hellacious fire, the 13th USCT Infantry Regiment, of which Henry Graham was a member, was the only regiment to reach the Confederate fortifications atop Overton’s Hill. They sustained forty percent casualties, and the division itself lost nearly 1,200 men total killed, wounded, or captured in the attack. However, their efforts struck home with many observers. Brigadier General James T. Holtzclaw was so astonished by the bravery of the Black soldiers that he commended them in his report: “they came only to die,” he stated. “I have seen most of the battle-fields of the West, but never saw dead men thicker than in front of my two right regiments.”

Holtzclaw was not the only one astounded by the performance of the USCT units. George Thomas had always believed that African Americans lacked the courage, discipline, and overall toughness to be good soldiers. Sherman’s advance into Georgia had deprived Thomas of many White soldiers, pressing many USCT units into Thomas’s service. Touring the field shortly after the battle, he saw thousands of Black Union corpses in heaps on the slow grade of the hill, intermingled with the bodies of White soldiers. Turning to Steedman, with whom he was riding, he exclaimed “gentlemen, the question is settled; Negroes will fight.” Thomas would later remark that the heroism and courage of USCT soldiers at Nashville “proves the manhood of the Negro.”

In the late evening of December 16, the fog of war was beginning to lift, revealing a massive Union victory. Of the nearly 30,000 Confederate troops engaged at Nashville, an estimated 6,000 were casualties, an astonishing rate of approximately 20%. Thomas’s force of 55,000 had only suffered 3,061 casualties, despite attacking entrenched positions. Hood proceeded to conduct a hasty retreat. The Army of Tennessee retreated for ten straight days, pausing only after crossing into Alabama and over the formidable Tennessee River. Hood finally recuperated at Tupelo, Mississippi, temporarily safe from a Union onslaught, with little more than half of the men engaged at Nashville. He resigned his command of the Army of Tennessee, ashamed of his performance, and was never again given field command of a Confederate unit throughout the duration of the conflict.

For many of the USCT soldiers profiled, the battle of Nashville and the subsequent pursuit of Hood to the Tennessee River represented their defining moment in the Civil War. In the aftermath of the Franklin-Nashville campaign, James M. Barnett was admitted to the General Hospital No. 1, commonly known as Wilson General Hospital, in Nashville on January 20, 1865. He unfortunately did not recover from his illness. Barnett died on April 18 at the age of 43. Army surgeons gave his cause of death as acute diarrhea.

Prince Bradford joined the pursuit from December 17 to December 27. After 1864, Bradford suffered from rheumatism caused by “heavy marching” that would keep him from regimental duty for the rest of the war. On June 12, 1865, he was admitted to the hospital in Nashville with an illness. He would later claim to have suffered a gunshot wound to his head during the war. Bradford mustered out on April 25, 1866, in Nashville.

Men like Arthur Clayton, Wilson M. Evans, and James Gilliam were also involved in the pursuit, and they all survived the war, mustering out after the cessation of hostilities. Others like Henry Graham, Henry Morse, and William Tucker, however, were not so lucky. Disease was rampant in camp life, and thousands of Black soldiers like these three died from maladies like smallpox and diarrhea. In reality, like many veterans of the USCT, these men would never get to live to enjoy the freedom they had sacrificed so much for.

Despite many soldiers from Albemarle County and Charlottesville passing away quite soon after the battle, many saw their legacy live on through a pursuit of a government pension to support their families. James M. Barnett is one such individual, as his family sought a pension for his Union army service. Barnett’s widow, Mary Ann, and her children continued to live in Waverly, Pike County, Ohio, after the war. She applied for a pension in 1866, but did not receive it until 1877, though the federal government did backdate the pension to the day after her husband's death. She initially received $8 a month and eventually received $20 starting in 1916. By the time of her death of senility on July 10, 1935, in Waverly, Ohio, she was receiving $50 a month. The lengthy application process highlights the many struggles that families, particularly African Americans, encountered in their quest for fair compensation for USCT soldiers’ sacrifices.

Prince Bradford was one of the lucky few to survive the war. Following his service, he moved to Huntsville, Alabama. He continued to work on the Bradford plantation as a farmer until at least 1896, despite living through illness and pain caused by injury during the war. Bradford's pension record does not give definitive evidence of who was in his family. At some point, Bradford was able to secure a pension with the help of his neighbors, fellow 17th USCT veterans, and even his former commanding officer, Captain John B. Nixon, who testified on Prince’s behalf. He was able to increase his pension in 1894 and 1895. He died on April 27, 1907, in Gainesville, Alabama. Doctors gave his cause of death as “senility.” Later, a woman claiming to be his daughter, Luvener Boylston, tried unsuccessfully to receive a pension, allegedly for taking care of Bradford's other surviving children.

After the war, Wilson Evans returned to Highland County, Ohio, where he lived for the remainder of his life. Evans had two sons with his wife Mary Evans Wilson, and actively sought a pension, but was rejected numerous times. He was often frustrated about the evidence requirements surrounding the pension. One time, Evans had even managed to produce five men from his company to testify on his behalf, according to his lawyer at the time. His ailments included having "deafness in both ears" that he contracted in January 1865 from a cold he caught from sleeping on the ground outside of Chattanooga. The cold had caused his head to swell, leading to hearing loss. Furthermore, he had trouble with rheumatism, which led to his inability to perform hard labor in the last years of his life. His rheumatism may have been connected with his hearing issues, and likely connected to his heart issues later on in his life. Even more frustrating for Evans was how he received his injury in the first place; he testified that army surgeons didn't treat his ear even though it “broke and run;” instead, the army merely compensated for the injury by assigning him to lighter camp duty until discharge. In his mind, this lack of treatment likely contributed to his deafness. His long struggle finally ended when Evans finally received his pension starting in 1885, receiving $12 per month. In January 1889, he was approved for a pension of $25 per month due to the severity of his deafness. Evans died several months later on June 12, 1889, due to heart failure brought on by severe rheumatism and bronchitis.

Following the war, James Gillum returned to Missouri. He briefly lived in St. Louis, until he moved to Quincy, Illinois, where he remained for the rest of his life. He worked as a preacher and a peddler. Gillum married his second wife, Annie Smith, on January 29, 1875, in Adams County. James and Annie enjoyed more than eight years together, until Annie passed away on April 25, 1883. Together they had one child: a daughter, Nellie G. Brown. Gillum died of lung disease in Quincy on June 9, 1887. Following his death, his daughter Nellie applied for a pension, but never received one due to an inability to prove he died from disease caused by his service.

Despite his relatively late change of heart regarding the use of Black soldiers in combat, the legacy of the USCT at Nashville was especially poignant for George H. Thomas. The general would go on to take an extremely active role in Reconstruction protecting the rights of newly freed slaves. At Nashville, the USCT had exceeded standards to duty in combat through their courageous attempts to take enemy positions, and their refusal to retreat in the face of overwhelming fire. For many men, including Thomas, African Americans had proven themselves through military service to be true men, and deserved to be treated as full citizens. Nashville, a smashing Union victory, is a prime example of this conversion.

For the Union, Thomas’s victory gave Sherman the freedom to devote his full attention to razing the Georgia countryside; nearly two weeks later, Sherman accepted the surrender of Savannah, a Northern triumph that seemed impossible just a short time ago. The combined victories also validated President Abraham Lincoln’s recent reelection, reassuring the public that the Union would pursue the war a successful conclusion.

In addition to their shared experience at Nashville, these African American soldiers born in the era of slavery in Albemarle County were united by a struggle for freedom, equality, and respect, they performed valiantly in battle, often against virtually impregnable Confederate positions. That they contributed to one of the Union’s most important victories in the West shows that their military careers were just as important as their more famous eastern counterparts. Their struggles to win their freedom for their friends and family members still held in bondage encapsulate a legacy of perseverance and courage.

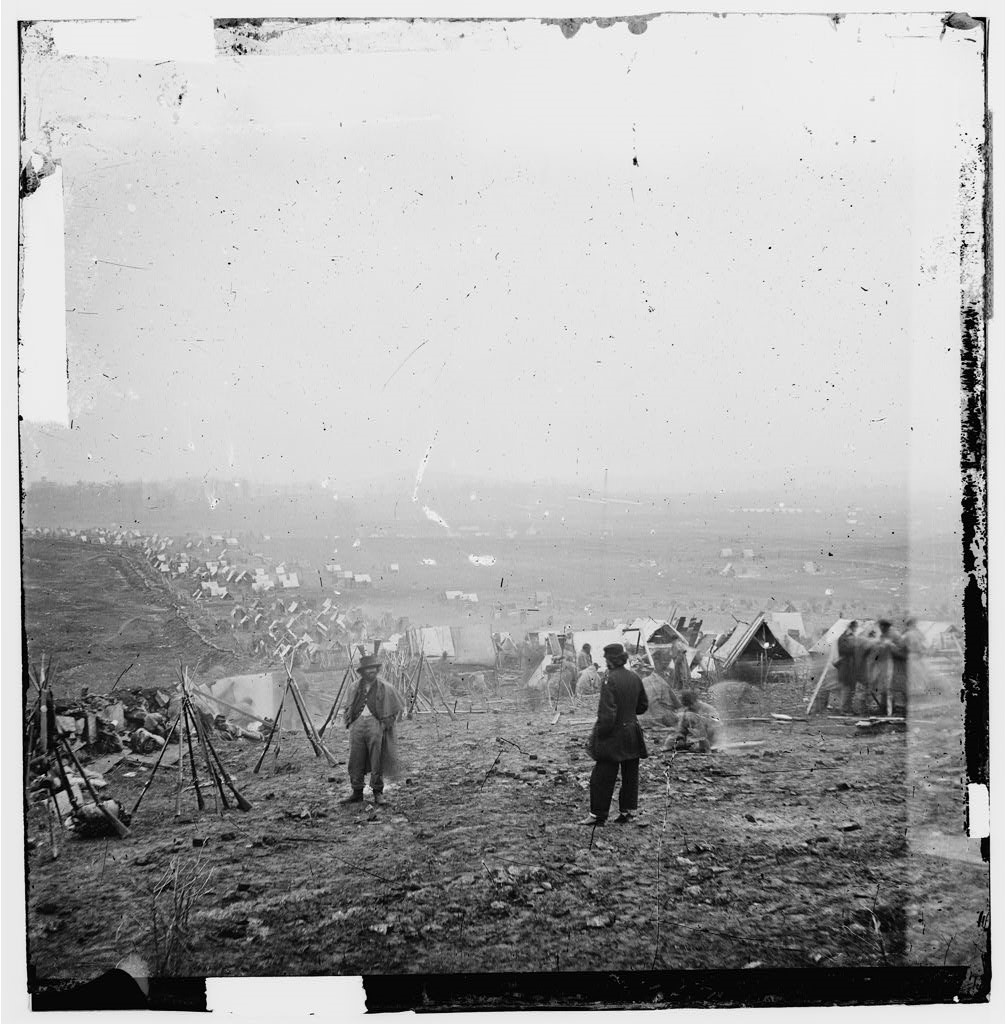

Images: (1) Battle of Nashville by Kurz & Allison (courtesy Wikicommons); (2) Major General George H. Thomas; (3) Federal outer line at Nashville in late 1864; (4) Major General James B. Steedman (courtesy the Library of Congress).

Compiled Service Records for James M. Barnett, Prince Bradford, Arthur Clayton, Wilson Evans, Henry Morse, James Gillum, William Tucker, Henry Graham, Washington Randle, RG 94, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Washington, D.C.; Pension Records for James M. Barnett, Prince Bradford, Wilson Evans, James Gillum, William Tucker, RG 15, NARA, Washington, D.C.; United States Federal Census, 1850; United States Cities Directory, 1822-1995, accessed through Ancestry.com; Frederick A. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion, vol. 3 (Des Moines, IA: Dyer Publishing Company, 1908); Freeman Cleaves, Rock of Chickamauga: The Life of General George H. Thomas (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1948); B. Noland Carter II, A Goodly Heritage: A History of the Carter Family in Virginia, vol. 1 (2003); Christopher J. Einolf, George Thomas: Virginian for the Union (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007).