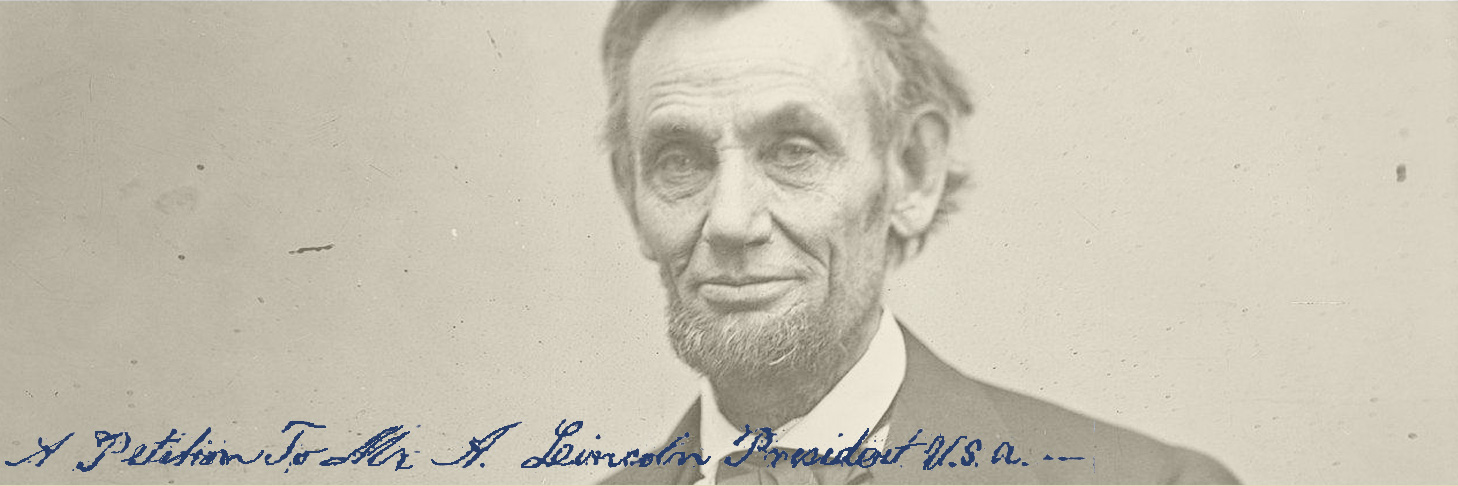

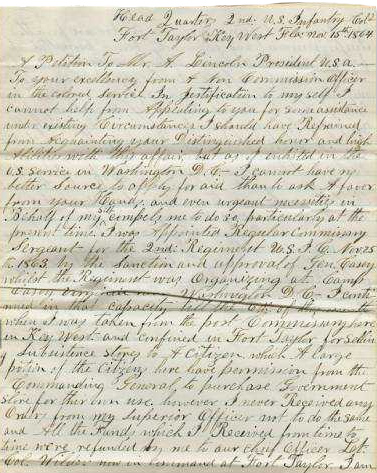

Confined at the headquarters of the 2nd U.S. Colored Infantry on November 15, 1864, Commissary Sergeant James T. S. Taylor put pen to paper to write President Abraham Lincoln a letter asking for release. “In Jestification to my self I cannot help from Appealing to you for some assistance under existing Circumstances,” wrote Taylor. “I should have Refrained from Acquainting your Distinguished honor and high Abilities with this affair, but as I enlisted in the u.s. service in Washington D.C.—I cannot have no better Source to apply for aid than to ask A favor from your Hands. and even urgeant necessities in Behalf of my self compels me to do so, particularly at the present time.”

Taylor informed the president that he had served as commissary sergeant for the 2nd USCT from November 25, 1863, until November 6, 1864, when he was arrested and confined by white officers in his regiment at Fort Taylor “for selling Subsistence stores to A citizen” (a local baker named Moffat) and receiving $500 in exchange. The officers recovered the money and arrested both Taylor and Moffat. Moffat was turned over to the federal district court in southern Florida, while Taylor was charged with “stealing” and held for military trial. Taylor maintained that, in the context of routine practices at the fort, he had done nothing wrong. “A large po[r]tion of the citizens here have permission from the Commanding General to purchase Government store for thir own use,” Taylor explained in his letter to Lincoln. Taylor assured Lincoln that “I never Received any Orders from my superior Officer not to do the same and All the Funds which I Received from time to time were refunded by me to our chief Officer Lt. Col. Wilder.”

Taylor’s letter to Lincoln testified to his desire to resume his soldierly duties in his regiment. He was “very Desirous of being Releaved or Release from this Imprisonment and captiverty being permitted if possible to seek A higher branch in the service which I think would only be Jestice” in light of his previous service to the Union. He concluded, “if my humble Appeal be Granted the favour would be thankfully Received and I hail with Joy that this may meet A favourable Consideration on your part. I am Sir Your humble soldier.” While the circumstances are unclear, Taylor does not appear to have ever gone to trial for stealing the commissary stores. Lt. Col. John Wilder noted that Taylor “has the merit of giving up the $500 which probably he might have effectually concealed.” Taylor was released from prison on March 2, 1865 and restored to duty.

Taylor’s desire for exoneration and reinstatement reflects just how much he had risked to join the Union ranks in the first place. He was 23 years old when he was drafted into the 2nd USCT in August 1863. According to his enlistment records, Taylor stood 5’ 8.5” tall with “dark” complexion and “black” eyes and hair. He worked as a shoemaker before joining the army. His father, also a shoemaker, had been born a slave but purchased his own freedom and moved his family to Charlottesville in the early 1850s. In his letter to Lincoln, Taylor described the ordeal he’d undergone as he made his way from Albemarle County to Union lines in Fairfax County, to avoid being coerced into doing manual labor for the Confederate army. “I haveing left my home in Charlottesville Alb. Co: Virginia two years Ago to Avoid the Rebel service my Journey was All most imparellel in Deluding the Rebel pickets and finally Reaching the union lines in safety,” he wrote. “I reported at the Head Quarters of Gen. Hays witch ware at Union Mills Va. Immediate on the Orange & Alexandria R.R.—the General Retained me and those Accompaned me at his Hd: Qurs: two weeks During which time I give him All the Information respecting the enemy and whereabouts that I know of.”

While at the front, Taylor kept the readers of the New York-based Anglo-African, one of the leading black newspapers of the day, abreast of the movements of the 2nd. In January 1864, he reported that the regiment “received a most favorable and kind reception from the citizens, both white and colored,” when they passed through the cities of Philadelphia and New York. A few months later, however, the men of the 2nd received a different reception when passing through a southern city. “They looked at us with as much wonder as though it was the first sight they ever beheld,” wrote Taylor, “and the last one they ever expected to see in this world.” Taylor impressed upon his readers that the men of the 2nd were eager “to strike a blow at rebeldom” and to fight to extend “liberty and freedom to the oppressed of our native land.”

Even while he was being detained at his regimental headquarters, Taylor continued to send correspondence to the Anglo-African, addressing the widespread discrimination against blacks within the Union ranks. In one letter, dated January 2, 1865, Taylor advocated for “equal privileges” for black soldiers, maintaining that it was unjust to deny black men the opportunity to lead black troops as regimental officers. “This spirit certainly does not agree with that manifested by the President in his different proclamations,” wrote Taylor. “Are we still to be deprived of all those rights and privileges which, by our sacrifices, we justly merit?” He continued, “This nation had to be taught some very severe lessons by Providence before they would even let the negro have a musket, and now, not until equal rights are given us as soldiers, will the God of all Wisdom lead the nation to a victorious triumph and a lasting peace.”

Six weeks after his release from detention, on April 18, Taylor married Eliza DeLancey, a woman he’d met while stationed at Key West. The couple had courted for six months, Eliza told a WPA interviewer in 1937, and married at the white Episcopal Church in Key West Florida, where Eliza taught Sunday school. Eliza had been born free in Key West to free black parents. Her father was literate, she recollected. “Knowd all his letters – A – B – C’s.” It is possible that Eliza’s father was the “colored citizen of Key West” who had held the $500 for Taylor.

Taylor’s last letter to the Anglo-African, dated July 26, 1865, three and a half months after the close of the war, found him still serving as Commissary Sergeant at Fort Taylor in Florida, and keenly following, through newspapers, politics back in Virginia. African Americans were planning a “colored convention” in Alexandria to demand the right to vote; Taylor was very sorry he could not “be present on the shores of Virginia to participate.”

But he was determined to get into the political fray and contribute to reforming his native state. Following Taylor’s discharge from the army in 1866, James and Eliza moved to Charlottesville. According to a biographical sketch published in 1945, Taylor returned to Virginia with $1000 in cash in his pocket, which he used to purchase land and build a two-story brick house.

In 1867, at the onset of Congressional Reconstruction, Taylor was elected to Virginia’s state constitutional convention, where he continued making the case for black civil and political rights, just as he had done in his letters to the Anglo-African during the war. (Curiously, Taylor’s father publicly opposed his son’s candidacy in favor of a white radical whom he thought would better represent the needs of the black community at the convention.) Calling the right to vote “the palladium of American liberty,” and pointing out that “the disloyal men of Virginia are seeking by every means in their power to prevent the free exercise of the elective franchise,” Taylor argued that Virginia ought to use paper ballots instead of viva-voce voting. The idea gained support and was incorporated into article III, section 2, of the 1870 state constitution, which began, “All elections shall be by ballot.”

Taylor remained active in Virginia politics until his death in 1918. He is buried in Oakwood Cemetery in Charlottesville.

Image: James T. S. Taylor to Abraham Lincoln, November 15, 1864 (courtesy National Archives).

James T. S. Taylor to Abraham Lincoln, November 15, 1864, RG 94 (Records of the Adjutant General’s Office), Entry 360 (Records of Divisions of the Adjutant General’s Office, Colored Troops Division, 1863-1889, Letters Received, 1863-1888 and Later), National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. (hereafter NARA); combined military service record and pension record for James T. S. Taylor, both at NARA; Anglo-African, January 30, April 9, June 4, 1864, and February 25, September 3, 1865; Luther Porter Jackson, Negro Office-Holders in Virginia, 1865-1895 (Norfolk: Guide Quality Press, 1945); Corey D. B. Walker, A Noble Fight: African American Freemasonry and the Struggle for Democracy in America (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008); Dictionary of Virginia Biography. Taylor’s military service record states that he was 19 years old when he enlisted; however, his pension states that he was born in 1840 and was 23 when he enlisted.