In December of 1915, the Black community of Jefferson County, Arkansas, gathered to bury the esteemed Black Virginian in Blue Matthew Gardner (alias Berry). Gardner had been born a slave in Albemarle County. Forced by the slave trade to move to Arkansas on the eve of the Civil War, Gardner fled bondage during the conflict, enlisting as a member of the United States Colored Troops (USCT). After the war, Gardner returned home to an Arkansas Delta in flux, where the ambitions of a Reconstruction coalition that included Blacks ran aground on the festering racial resentments of most White southerners. Girded by the support of wartime comrades and the local Black community that would later lay him to rest, Gardner endured throughout the chaotic ensuing decades, navigating between the shoals of the largely failed promises of Reconstruction, the dangers of white supremacist violence, and the pressing problem of poverty. His story thus exemplifies the sacrifices, sufferings, and survivals of African Americans in postwar Arkansas.[1]

What little we know directly of Gardner comes from his pension records. As he recorded in his laborious, prolonged fight for successive pensions, discussed further below, Gardner had been born into slavery in Albemarle County in 1847. His owner, the Fretwells, were a prominent area family, possessing a series of predominantly tobacco and corn-based plantations. By the late 1850s, however, the Fretwells had descended deep into debt. In 1859, upon the death of the family matriarch, they undertook an extensive sale of property that included the young Gardner. Gardner subsequently embarked upon a forced migration to Arkansas, experiencing the horrors of the domestic slave trade—a long, brutal journey in which men, women, and children, having been torn apart from their own families, were bound together in chains. His voyage from Virginia to Arkansas was part of a broader pattern: as Upper South plantations declined in productivity over the nineteenth century, Virginia became the principal exporter in the domestic slave trade, selling slaves to the more profitable, cotton-growing regions of the Deep South, including the Arkansas Delta.[2]

In Jefferson County, Gardner became the property of the Berry family, prominent businessmen deeply entwined in the capitalist-fueled expansion of cotton plantation slavery in the region. It was here that Gardner, at the instigation of his owner, temporarily took on the surname of Berry. At his new home outside Pine Bluff, a plantation known as Berry Place, Gardner became enmeshed in a typical slave community on the frontier, consisting largely of forcibly transplanted migrants from the Upper South like himself. Such neighborhoods were by nature fleeting and transient, subject to the whims and fancies of plantation owners. Enslaved persons in such settings as Berry Place nevertheless forged enduring ties in the face of adversity, constructing resilient, shared networks of kinship, culture, and support amongst themselves. These bonds would become the building blocks of later, post-emancipation communities, including the one that would sustain Gardner in his postwar years.[3]

When the Union army arrived in Arkansas in the early years of the Civil War, Gardner, like many others, voted with his feet by fleeing to Federal lines. In the fall of 1864, he enlisted in the 69th USCT Infantry Regiment under the name of Matthew Berry—a fact that would complicate his later attempts to garner a pension. Reassigned to the 64th USCT Infantry Regiment, Gardner would engage in garrison duty throughout Arkansas and Mississippi through the end of the war and beyond. Within the ranks of the regiment, he reaffirmed bonds with fellow escapees from Berry Place such as Thomas Washington and forged new ties of kinship with men like Harrison Tucker, Daniel McHenry, and Isaac Gray. This enlarged support network would endure long after the war, as his comrades became his new neighbors in Jefferson County upon mustering out in 1866.[4]

The home to which Gardner returned was in turmoil, buffeted by a simmering conflict between Republicans and white supremacist Democrats. In 1867-8, following the congressional implementation of Radical Reconstruction, Republicans swept to statewide power, forging an unwieldy coalition of White northern transplants, southern Whites, and African Americans. To an extent, Republican rule offered a moment of promise to Black Arkansans like Gardner. As historians have detailed, the Republican coalition overcame vehement, white supremacist opposition, grounded in explicitly racist arguments deploring the notion of Black citizenship and social equality, to pass a groundbreaking state constitution in 1868. This constitution gave African Americans the rights of public education, legalized marriage, and suffrage, paving the way for the election of Black officeholders throughout the state—a trend that would even endure, in limited fashion, in Jefferson County for a time after Reconstruction. The Freedmen’s Bureau, created to aid in the provisioning and employment of former slaves, precipitated an intra-southern migration of former slaves to Arkansas. The Bureau presented the state as a land of economic opportunity and relatively little racial prejudice—a sentiment echoed by the Black minister Henry McNeal Turner, who labeled Arkansas “the great Negro State of the Country.”[5]

Such words, however, vastly overstated the economic and political realities of postwar Arkansas. Black Arkansans, as historians have shown, faced a dire lack of economic opportunity, even during the brief period of Reconstruction. Republican officials did not reverse the restoration of plantation lands to ex-Confederates after the war. On the contrary, the Freedmen’s Bureau largely resorted to inducing former slaves to return to the fields, often on their old plantations, as contract laborers. Bureau officials engaged in Arkansas boosterism to pressure planters in neighboring states like Georgia to raise their wages. Black landowning, despite their intimations of opportunity, was never in the cards. Rather Black laborers became mired in crushing cycles of debt and poverty as sharecroppers and tenants. Even so, Bureau leaders in Arkansas promoted wage labor as the paramount duty of freedom, discouraging Black political participation as a waste of time—a sideshow that would make them “neglect their business.”[6]

White supremacy, moreover, was resurgent in postwar Arkansas. Waves of mass lynching and anti-Black violence swept across Jefferson County in the years after the war. After the passage of the 1868 constitution, terrorist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan emerged, bent on restoring the old racial order through violence. Rather than fight this emerging threat, Arkansas Republicans turned on each other, enlisting competing Black militias in a bloody conflict known as the Brooks-Baxter War. Aided by this factional strife and the splintering of Republican rule, the Klan and their allies achieved the so-called “Redemption” of Arkansas, returning the state to Democratic hands in 1874. Democrats went on to reverse African Americans’ Reconstruction-Era gains. Though Jefferson County persisted for a time as a pocket of biracial, fusionist politics grounded in agrarian populism, by the 1890s Democrats had perfected a comprehensive regime of mass disfranchisement and Jim Crow segregation. Lynching, a fundamental tool of white supremacy, remained a tragically common occurrence in the area. Confederate veterans’ organizations dedicated to the enshrining of the white supremacist Lost Cause, such as the United Confederate Veterans, also became active in the Pine Bluff region.[7]

It was this maelstrom of economic and political trouble to which Gardner, now using his former surname, returned after the war. Gardner became a sharecropper for Solomon Franklin, a White planter who had rented Berry Place after the Civil War and who had, with the help of the Freedmen’s Bureau, induced many formerly enslaved laborers to return to the land. While raising a large family over the postwar decades, Gardner struggled to survive not only against manmade obstacles but also against natural ones, being struck by lightning in 1883. Against such odds, however, Gardner persevered. By the 1890s, he had become a direct, cash tenant for the Berry family, relatively improving his economic lot. Drawing on his enduring networks of kinship, Gardner also became a local community leader. He was able to ascend to political office for a time as well, serving as a justice of the peace in Jefferson County in the early 1900s.[8]

Perhaps the greatest trial Gardner endured, and the one most illustrative of the necessity of communal bonds in the African American struggle to navigate postwar oppressions, was his continuous struggle for federal pensions. The Black fight to secure pensions, as historians have detailed, was about far more than money. In the face of their almost total erasure from public life, pensions offered proof of their sacrifice—of their sacrifices as patriotic Americans, and their consequent rights as free and equal citizens. 1890, the federal government expanded its original pension policy, which compensated only soldiers disabled during wartime service, to include all disabled soldiers, regardless of when they incurred their disability. Wartime-disabled veterans, however, would receive a much larger pension than their otherwise-disabled counterparts. Gardner, who suffered from heart disease, applied to receive the larger pension in 1890, arguing that he had incurred his condition during the war. Over his ensuing, decades-long battle, Gardner ran up against the prejudicial policies of the government. As historians have detailed, the applications of Black veterans like Gardner were subject to greater scrutiny from officials than those of White applicants. Gardner, having enlisted as Matthew Berry, drew especial scrutiny.[9]

Gardner nonetheless fought to secure his due. He amassed large depositions of evidence in favor of his claim, recounting his life experiences and his disabilities. To secure the larger pension, Gardner made sure to explain that he came home in 1866 “sick with the same disease” from which he now suffered. Beset by competing, contradictory claims from medical examiners, Gardner turned for testimonial support to his friends in the community. “I have men around here who know me,” he explained. And, indeed, he did. Fellow veterans and neighbors, including Tucker, McHenry, and Washington, submitted testimonials on his behalf. All stressed his longtime disability. Washington, for example, explained that Gardner was a “continuous sufferer from heart disease.” Sustained by such bonds, Gardner achieved a limited success after seven long years, securing a pension—but only a limited one, as an otherwise-disabled veteran.[10]

Unsatisfied with such an outcome, Gardner fought on. Though he was never able to secure government recognition of his wartime disability, Gardner gained a larger pension in 1908, after Congress amended the pension law to recognize old age as a qualifying disability. And, upon his death in 1915, the comrades that attended his funeral, led by Washington, secured a widow’s pension support for his wife, Margarett. The story of Gardner is thus one of perseverance and resilience in the face of oppression of hardship—and of the role of Black communal ties in carving places for men like Gardner in the harsh world of postwar Arkansas. Aided by his comrades in arms, the Black Virginian in blue finally received his due as a citizen-soldier.[11]

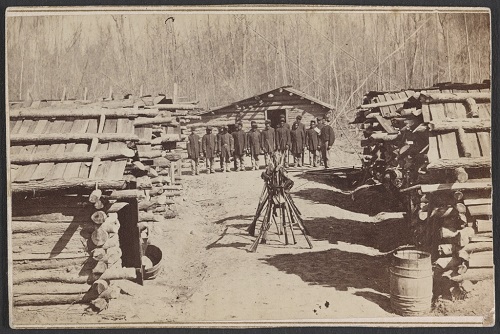

Image: Quarters of the 64th USCT Infantry Regiment at Palmyra Bend, Mississippi (courtesy Library of Congress).

[1] Elizabeth R. Varon, “From Albemarle County to the Arkansas Delta: USCT Pensions as a Window into the Domestic Slave Trade,” Nau Center for Civil War History, University of Virginia. This post draws heavily on the abovementioned essay.

[2] Varon, “From Albemarle County.”

[3] Varon, “From Albemarle County” and Dylan Penningroth, The Claims of Kinfolk: African American Property and Community in the Nineteenth-Century South (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2003).

[4] Varon, “From Albemarle County.”

[5] Varon, “From Albemarle County”; Hannah Rosen, Terror in the Heart of Freedom: Citizenship, Sexual Violence, and the Meaning of Race in the Postemancipation South (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2009); and Story Matkin-Rawn, “‘The Great Negro State of the Country’: Arkansas’s Reconstruction and the Other Great Migration,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 72, no. 1 (Spring, 2013): 1-41.

[6] Varon, “From Albemarle County”; Matkin-Rawn, “Great Negro State”; Rosen, Terror in the Heart of Freedom; and The Weekly Arkansas Gazette, quoted in Rosen, Terror in the Heart of Freedom, 122.

[7] Rosen, Terror in the Heart of Freedom; Earl F. Woodward, “The Brooks and Baxter War in Arkansas, 1872-1874,” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 30, no. 4 (Winter, 1971): 315-36; Varon, “From Albemarle County”; and “Reunions in Arkansas,” Confederate Veteran XVII (Dec., 1909): 579-80.

[8] Varon, “From Albemarle County.”

[9] Varon, “From Albemarle County” and Elizabeth A. Regosin and Donald R. Shaffer, eds., Voices of Emancipation: Understanding Slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction through the U.S. Pension Bureau Files (New York: New York University Press, 2008), esp. pp. 3-4.

[10] Varon, “From Albemarle County.”

[11] Varon, “From Albemarle County.”