Out of the approximately 18,000 African American sailors who served in the Union navy during the Civil War, over 2,800 were born in Virginia, the most from any state. While most of the men in our Black Virginians in Blue project were soldiers in the USCT, six served as sailors aboard five Union vessels. Through the use of naval service records, accessed through the National Park Service’s Soldiers and Sailors Database, and secondary sources on the wartime navy and Black sailors, we have produced a preliminary reconstruction of the wartime experiences of our Albemarle sailors. Black sailors greatly aided the Union war effort because they provided much needed labor on ships that helped defeat the Confederacy.

Our six Albemarle-born sailors were Joseph Brown (aged 18 at time of enlistment), Alexander Caine (21), John Edwards (19), Harry Hill (29), David Linton (33), and Henry Murray (19). With the exception of Alexander Caine, who enlisted in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in January 1862, the other Albemarle sailors enlisted after the fall of 1863. In fact, Brown, Edwards, Linton, and Murray all enlisted at Skipwiths Landing, Mississippi, between the fall of 1863 and the spring of 1864. Furthermore, with the exception of Harry Hill who served as a Captain’s Cook, our Albemarle sailors were given the entering rank of landsman, the second lowest rank in the Union Navy. Caine, Edwards, Linton and Murray all served until the summer of 1865, when their ships were decommissioned. Unfortunately, Joseph Brown’s naval muster records do not extend past March 31, 1864 and thus without additional records his fate remains unknown. Harry Hill was the sole Albemarle sailor who enlisted for one year and thus did not serve until the end of the war.

Due to his rank and time of enlistment, Alexander Caine was most likely a free man;* however the legal status of the other five Albemarle sailors remain unknown, as the U.S. Navy did not require enlistees to designate whether they were free or enslaved at the time of enlistment. Historian Joseph P. Reidy estimates that “nearly three men born into slavery served for every man born free.” Thus some of these sailors were likely slaves when they enlisted in the Navy. Apart from the legal status of each of our men, specific details of their wartime service are difficult to find. There are no naval equivalents of the Union Army’s compiled military service records, which the government created after the war in order to streamline the process of determining eligibility for post-war pensions. Yet, insight into these sailors’ experiences in the war can be gained by examining the general wartime experiences of African Americans in the Union Navy and the different types of vessels on which these Albemarle sailors served.

In contrast with Black soldiers in the Union army, Black sailors served on technically integrated vessels and received equal pay, equal rations, and equal medical care. Yet, despite this supposed equality between Black and White sailors, racial prejudices continued to exist in the navy. While the Department of the Navy did not establish a formal system of racial separation, de facto segregation existed due to the guidelines detailing directions for recruiting and rating Black sailors issued by the Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles. These guidelines reinforced the widespread racial prejudices that African American’s were naturally inferior and subservient to Whites by regulating Black sailors to serve in unskilled positions such as laborers and servants, not as skilled seamen. For example, racial prejudice influenced the entering rating of Black sailors. At the time of enlistment, recruiters gave enlisting sailors a rating that reflected the naval experience of the enlistees. Those with no previous naval experience were given the lower ratings of boys and landsmen and those with naval experience were rated as ordinary seamen and above. Despite cases of previous naval experience, over 82% of Black sailors were given the unskilled ratings of boys and landsmen.

Among our Albemarle sailors, the Navy gave five the entering rating of landsmen, which provides insight into their day-to-day roles on Union ships. While not the lowest naval rating, landsmen were assigned unskilled tasks such as hard labor duty and also worked as deck crewmen. Due to the lack of formal training programs within the Union navy, landsman learned naval skills on duty. Additionally, the Union navy paid landsmen $12 a month but withheld payment until expiration of service which discouraged desertion and reduced gambling and drunkenness aboard vessels. One Albemarle sailor, Harry Hill, enlisted as a Captain’s Cook, which was a staff petty officer’s position. Staff petty officers represented about 8% of Black sailors and did not receive an official ranking at enlistment. Rather, staff petty officers were skilled in domestic areas and thus served as either cooks or stewards. They received more pay than landsmen or boys, often receiving between $25 and $30 per month. The predominance of Black staff petty officers reinforced the racial prejudice that African Americans were naturally suited to domestic tasks.

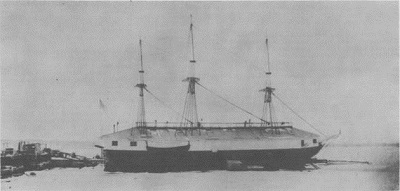

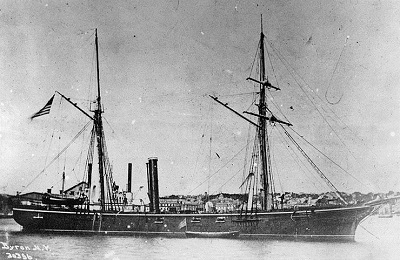

In addition to our Albemarle Black sailors’ ranks, the different types of vessels they served on provides further insight into their wartime experiences. The five vessels can be broken down into three categories: ocean going, blockade, and Mississippi River vessels. The USS St. Louis, a sloop-of war, belonged to the first category. It was commissioned on December 20, 1828, and decommissioned on May 12, 1865. Alexander Caine served on this vessel while she completed trips across the Atlantic Ocean. From late February 1862 until late November 1864, the St. Louis was on patrol off the African coast, the Canary Islands, and the Azores in search of Confederate commerce raiders. After November 1864 and until the end of the war, the ship engaged in blockade duty as part of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron.

The second category of blockade vessels included the USS St. Louis post-November 1864 and the USS Marblehead. During the war, blockade vessels participated in the Union blockade of the Confederacy’s Atlantic and Gulf coasts. Sailors considered blockade duty to be incredibly tedious, as it required long days at sea with minimal change in scenery and schedule and limited chance of combat. Harry Hill served on the Marblehead, which was a screw gunboat and also part of the South Atlantic Blockade Squadron. However, in contrast with the St. Louis, the Marblehead engaged in combat twice during the war, once while Hill was serving on board. While on duty near Legareville, South Carolina, on December 25, 1863, the ship suffered 20 hits in a duel with Confederate seacoast howitzers. Nonetheless, the Marblehead successfully fought off its attackers, leading to the subsequent capture of two of the enemy’s guns.

The last category consisted of vessels that served on the Mississippi River. These included the USSThistle, the USS Louisville, and the USS Laurel. The Thistle was a swift gunboat that served in the Mississippi Squadron from October 1, 1862, until her decommission on August 12, 1865. Joseph Brown served aboard this ship when she engaged in dispatch and reconnaissance duty along the Mississippi River.

The War Department transferred the Louisville, an ironclad centerwheel gunboat, to the navy on October 1, 1862, after which she remained a member of the Mississippi Squadron and saw action at the seize of Vicksburg. Yet, by the time John Edwards, David Linton and Henry Murray joined her crew, she had returned to patrol and army support duty and remained there until decommission on July 21, 1865. As part of the spring 1864 expedition up the Red River, the Louisville engaged in limited combat near Columbia, Arkansas, and Skipwiths Landing, Mississippi, in June.

After her transfer to the navy on August 30, 1862, and until the end of the war, the USS Laurel, a screw steamer, supported both army and navy operations, which attempted to cut western Confederate supply lines to the Eastern Theater. Throughout the course of war, the Laurel never engaged in naval combat, including the months in 1864 when Henry Murray served on the ship prior to his transfer to the Louisville. Thus, the Albemarle sailors on these Mississippi River vessels mainly participated in patrol and reconnaissance duty while seeing little combat.

We hope that additional research in naval and census records at the National Archives will provide more information about these Black sailors and their lives before and after the war. By examining the vessels they served on and studying the overall experiences of Black sailors in the wartime navy, one can conclude that our six Albemarle-born Black sailors largely participated in unskilled daily labor and saw very little combat. While their general experiences lack traditional notions of valor and heroism popularly associated with Black Union soldiers as seen in the movie Glory, African American sailors were crucial to the war effort as they provided labor that the Union Navy desperately needed. Thus our six Albemarle sailors contributed to Union victory despite the prejudices they faced in their naval careers.

*According to Reidy, prior to December 1862 all enlisting contrabands were given the rating of boy. A barber, Caine was living in Philadelphia when he enlisted in January 1862 and was given the rating of landsmen. Thus the Navy did not consider Caine to be a recent runaway slave and he was probably free at the time of his enlistment (Joseph P. Reidy, “Black Men in Navy Blue During the Civil War,” Prologue: of the National Archives and Record Administration 33, no. 3 (Fall 2001), http://www.navyandmarine.org/ondeck/1862blackinblue.htm).

Images: (1) Unknown Black sailor from the Civil War (Library of Congress). (2) Sloop-of-warUSS St. Louis (Wikicommons). (3) Screw gunboat USS Marblehead (Wikicommons).

Naval service records were accessed for each of our sailors through the National Park Service's Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Database, https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/soldiers-and-sailors-database.htm; Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships entries for “Laurel I (Screw Steamer),” “Louisville I (Iron Clad Centerwheel Gunboat),” “Marblehead I (Sc Gbt),” “St. Louis I (Sloop-of-War),” and “Thistle I (Sw Gbt)” were accessed online at the Naval History and Heritage Command website, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs.html; Joseph P. Reidy, “Black Men in Navy Blue During the Civil War,” Prologue: of the National Archives and Record Administration 33, no. 3 (Fall 2001), http://www.navyandmarine.org/ondeck/1862blackinblue.htm; Steven J. Ramold, Slaves, Sailors, Citizens: African Americans in the Union Navy (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2002); Barbara Brooks Tomblin, Blue Jackets and Contrabands: African Americans and the Union Navy (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2009).