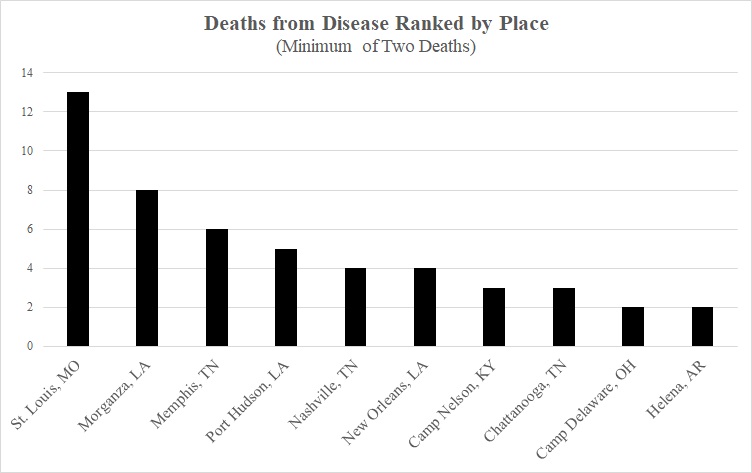

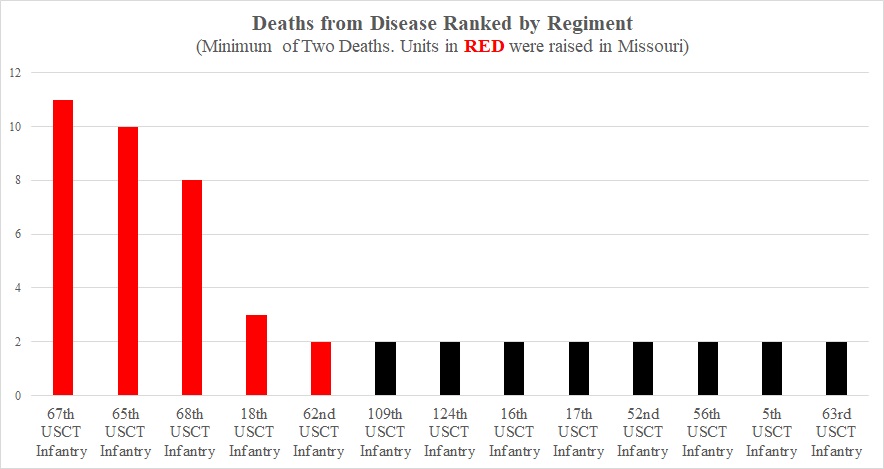

Approximately 180,000 African American men enlisted in the Union Army during the Civil War. In examining compiled military service records online at Fold3.com or at the National Archives, we have so far discovered that 251 of these Black soldiers were born in Albemarle County, Virginia. Of those Albemarle men, 72 died while serving in the army, a 28.8% mortality rate that is significantly higher than the 18.5% figure for all USCT soldiers. We believe this disparity to result in part from the concentration of 41 Albemarle men in the deadly 65th and 67th USCT Infantry regiments, both of which suffered large numbers of casaulties from disease. Overall during the war, 66 Albemarle USCT soldiers died from disease while only five died from battle wounds (another died as a result of an accident).

Benton Barracks, Missouri, is well established as one of the unhealthier locations for USCT soldiers. More than 30,000 men were housed at Benton Barracks, including Albemarle men of the 65th Regiment. Although the 65th USCT never witnessed combat, it is recognized as one of the regiments with the highest mortality rates. Tightly housed in five buildings, the soldiers of the 65th USCT experienced a rapid spread of disease. Thirty died before being mustered in, and more than 100 before taking the field. Three of the 22 Albemarle men of the 65th USCT (nearly 14%) died at Benton Barracks.

Louisiana proved to be the deadliest state in our sample, with nineteen deaths from disease overall and eight at Morganza Bend. USCT units at Morganza Bend suffered especially heavy losses from disease. The 16,000 soldiers in the hot, swampy area of southern Louisiana encountered diarrhea and typhoid as major killers. In the final period of the war, many of the 65th and 67th were stationed in a state that historian Margaret Humphreys called the “mass graveyard for black troops.” These regiments coped with extreme weather and insufficient supplies. A colonel of the 67th USCT estimated one to three deaths daily in Louisiana.

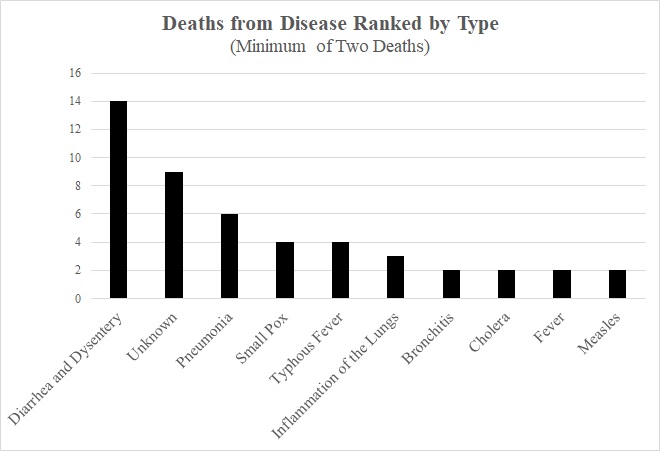

Of the 66 Albemarle men who died from disease while enlisted in the army, we do not know the specific cause for nine soldiers. We hope that future research in pension records and other sources may provide answers. For our known sample, the top three killers were diarrhea/dysentery, pneumonia, and small pox. This list is reflective of broader trends for USCT men. African American troops were more susceptible to these diseases than their White counterparts. Most significantly, a USCT soldier was five times more likely to contract small pox than a White soldier in the same area.

In our sample, diarrhea or dysentery killed fourteen Albemarle men. Diarrhea/dysentery accounted for nearly 35% of all USCT troops who died from disease during the war. In each year of the war, diarrhea/dysentery placed in the top two for deadliest diseases, with a high number of instances in Louisiana. This trend holds true for our sample. The swampy environment of Louisiana claimed nine of the fourteen Albemarle men who died from the disease. It is important to note that other diseases commonly accompanied diarrhea, and surgeons and other medical staff may have underreported cases.

Pneumonia ranked second for deadliest disease in our sample with six victims. Over the course of the war, pneumonia claimed 30% of deaths from disease in USCT units. Of our six cases, four died at Benton Barracks. Throughout the war, the medical staff there reported nearly 800 cases and 150 fatalities. Soldiers at Benton Barracks also contended with outbreaks of measles, which spread rapidly in the close quarters, weakened immune systems, and likely left many soldiers primed to contract pneumonia.

The third major killer for USCT soldiers was small pox, which killed four of our soldiers during the war (another man, Isaac Underwood, succumbed to the disease only months after being discharged for disability in November 1865). Across all regiments, small pox accounted for 13% of all disease related deaths. Benton Barracks proved to be a hot spot. In the 65th, nearly 100 soldiers contracted the disease and 41 died. But the majority of our sample who died from small pox served in Tennessee. Only one of the Albemarle men died at Benton Barracks. Overall, USCT soldiers died from higher rates of small pox than their White comrades. Several factors probably contributed to this phenomenon. Modern scholarship reveals that the small pox vaccine, which had been in existence for many decades, was not readily available to African American soldiers. Moreover, some scholars point to environmental backgrounds, suggesting that soldiers who grew up in more urban areas were exposed to the disease and built immunity. Most former slaves, who made up the bulk of the USCT units, lived far from cities and exposure to small pox.

These data regarding mortality among Albemarle County USCT men emerged from our original pass through the sample and are preliminary findings. Further research will explore other locations as well as the impact of disease on men who survived. Over the course of the war, for example, almost 88% of the 54,000 USCT soldiers who contracted diarrhea or dysentery did not perish. Additionally, it may be fruitful to consult pension records and other sources to examine the effects of disease on soldiers after the war’s conclusion.

(5/18/2021: Project Director William Kurtz has updated this blog entry to reflect the project’s latest findings.)

Compiled Service Records, RG 94 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., accessed for each soldier through Fold3 (https://www.fold3.com/browse/273/); Margaret Humphreys, Intensely Human: The Health of the Black Soldier in the American Civil War (2010); Bonnie Brice Dorwart, M.D., Death is in the Breeze: Disease during the American Civil War (2009).