If this is your first visit to UVA Unionists, we recommend that you read the overview essays by Lily Snodgrass, Will Kurtz, and Matthew Weissenfluh first before exploring the others. Essays include deeper explorations of noteworthy UVA Unionist soldiers, sailors, and politicians. In order to filter essays, unclick the checkmark next to the types of essays (overview, people, places, or battles) that you do not want to see. Essays can be searched for keywords by using the search bar in the site's header.

UVA Unionists in the War

In 1860, the University of Virginia (UVA) was a bastion of pro-slavery ideology, filled with scions of the South’s most politically and economically elite families. Its students were overwhelmingly descendants of the southern gentry, with family histories often traced back to the pre-Revolutionary era. The vast majority of the students came from families that owned slaves, and thus “the university’s history was… tied inextricably to the history of the South.” Pro-secessionist sentiment, pro-slavery attitudes, and a culture steeped in the concept of southern honor were key principles for many of these students’ lives. Nevertheless, the University of Virginia had sixty-nine men, including students, alumni, and faculty, who fought for the Union during the American Civil War.

UVA Unionists After the War

After the Civil War, the University of Virginia made significant efforts to commemorate its Confederate past. No such honors or special recognition have ever been bestowed on the sixty-nine Cavaliers who fought for or supported the Union, their stories neglected by a University that actively embraced the Lost Cause version of Civil War history. Despite the fact that this group of Union Veterans was overwhelmingly made up of prominent citizens in their communities, these Union men who were granted victory were denied the “glorious immortality” bestowed upon their southern counterparts, both on and off UVA’s grounds.

“Neglected Alumni”: UVA’s Union Soldiers and Sailors (updated)

In 2017, the Nau Center has only began to recover the stories and experiences of those University of Virginia alumni and students who fought for the Union during the Civil War. The Center hopes that “UVA Unionists” will complicate the traditionally Confederate-dominated local history of Charlottesville and UVA during the war. (updated April 27, 2021)

Confederate Military History of the University of Virginia

As the flagship institution of higher education in the state upon the outbreak of the Civil War and a bastion of proslavery ideology and secessionist fervor, the University of Virginia and its alumni proved vital to the Confederate war effort, contributing a substantial portion of its alumni who served in the military.

Hoos in the Hoosier State: The 149th Indiana, UVA’s School of Medicine, and Post-War Reconciliation (Part 1)

While many of our UVA Unionists attended the University before the war, very few enrolled after their service. In 1869, two young men from Parke County, Indiana, travelled hundreds of miles south to enroll in the University of Virginia School of Medicine. As veterans of the 149th Regiment, Indiana Volunteer Infantry, Marion Goss and Joseph Noble starkly contrasted with the typical UVA student profile. At the time, the vast majority of the faculty and student population maintained ardent pro-Confederate views, and many had served in the Confederate army. According to a eulogy given at Goss’s funeral, Noble and Goss were the only northern students at the University during their tenure.

Hoos in the Hoosier State: The 149th Indiana, UVA’s School of Medicine, and Post-War Reconciliation (Part 2)

Marion Goss and William H. Gillum’s friendship arose through surprising circumstances, given that Gillum had served in the Confederate army. Born on November 22, 1847, in Augusta County, Virginia, Gillum was the son of Dr. Pleasant G. Gillum, another UVA School of Medicine alumnus. William H. Gillum’s grandfather was a successful planter and an early settler of Albemarle County. Exactly one day before Jacob D. Mater enlisted in the 149th Indiana, Gillum enlisted in the Staunton Artillery of the Confederate army on January 24, 1865. Gillum was present at Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, and his name appears on a list of paroled prisoners. Like his father, Gillum enrolled in the UVA Medical School in 1867. The following year, he transferred to the College of Physicians and Surgeons in Baltimore, Maryland, from which he graduated in 1869. Gillum then returned to Augusta County to practice medicine.

Westward the Course of American Empire: UVA Unionists and 19th Century American Expansion

Of the Union veterans who attended the University of Virginia, nearly a dozen pursued military careers after the Civil War. This blog will discuss the lives of Wray Wirt Davis and George Worth Woods in depth. While Davis was a southerner and a cavalry officer, Woods was a navy physician from the North.

Finding UVA's Unionists (Part 1): William Meade Fishback

In October 1913, the Staunton Daily News published an editorial criticizing the lack of attention paid to Virginia students who served in the Union military during the Civil War. In the preceding decade, the University of Virginia had celebrated its Confederate alumni by hosting reunions, casting medals, and dedicating a plaque on the Rotunda. The university had compiled a list of just more than 2,000 Confederate alumni, but it had made no attempt to honor its Union veterans and rarely acknowledged their existence. UVA’s Alumni News reprinted the editorial later that month, acknowledging that “no complete list has been made of the University alumni who saw service in the Union army.”

Finding UVA's Unionists (Part 2): James Overton Broadhead

As the seven Lower South states seceded in the wake of Abraham Lincoln’s election, Unionists in the Upper and Border South struggled to hold their fracturing country together. Many of these Unionists insisted the country could endure “half slave and half free”—as it had for more than eighty years—and they worked tirelessly to contain the crisis by finding a middle ground in the debates over slavery. Their efforts failed, however, because southern secessionists and hard-line Republicans refused to compromise, but also because of divisions within the Unionist ranks. Members of this Unionist coalition could vary dramatically in the nature and strength of their national attachment, and in their understanding of the relationship between slavery and Union. These divisions helped shape the secession crisis as well as the course of the Civil War and Reconstruction. The life of James Broadhead of Missouri encapsulates these tensions.

Finding UVA's Unionists (Part 3): Joseph Cabell Breckinridge

In the decades following the Civil War, the University of Virginia erased its Union veterans from its history, constructing a narrative of unwavering Confederate commitment. The few writers who mentioned these UVA Unionists insisted that they were northern students, thereby reaffirming the image of southern unity. In 1906, Captain William W. Old, a veteran of the Army of Northern Virginia who had attended the university in 1860, argued that almost every one of his classmates volunteered to serve the Confederacy—“with the exception of a few from the Northern states and a few, very few, from Maryland.” A 1913 editorial in The Staunton Daily News insisted that there “must have been numbers of northern boys and young men who attended the University of Virginia…who stuck to their people and their native land when the war broke out.”

UVA’s European Revolutionary: The Life of Joseph Emile d’Alfonce

Every evening, students recalled, the hills around antebellum UVA resounded with the music of La Marseillaise, the anthem of the French Revolution. Joseph d’Alfonce, the University’s gymnastics instructor, began the call to arms in his “splendid baritone,” and soon hundreds of students’ voices filled the air. For d’Alfonce, the anthem’s promise of “cherished liberty” triumphing over tyranny carried special meaning. He had fought in one revolution and lived through another, and twice he had been forced to flee from arrest. By 1851, he had settled in Charlottesville, where he built a quieter life teaching French and gymnastics. The outbreak of Civil War, however, shattered any complacency, testing his loyalties and forcing him to flee his new home in Virginia.

“A Loyal Virginian”: Southern Honor, Unionism, and the Life of Major Henry Thomas Dixon

In the 1860 presidential election, only one person in all of Fauquier County, Virginia, voted for President Abraham Lincoln: a wealthy slaveholder named Henry Thomas Dixon. Five years later, after serving as a paymaster in the Union army, he was gunned down in a duel with a former Confederate surgeon on the streets of Alexandria.

"Efforts of Reform”: UVA Unionist Robert H. Shannon and the Pursuit of Progress

Most UVA Unionists—men like William Fishback, James Broadhead, and Albert Tuttle—viewed themselves as conservative men trying to preserve, rather than transform, their world. They rejected political radicalism, sought compromises to avert secession and Civil War, and often accepted post-war reconciliation with former Confederates. New York lawyer Robert Henry Shannon, however, embraced the possibilities of progress. As a Whig and a Republican, he insisted that government action could solve society’s problems and protect Americans’ liberties. He championed Radical Reconstruction, women’s suffrage, and the Greenback Labor movement—but he also sought to disenfranchise immigrants and impose Victorian morality on the working class. His political career reflects the fraught history of many nineteenth-century benevolent movements, which worked to perfect society by “reforming” the lives of its most vulnerable members.

Albert H. Tuttle: UVA's Unionist Professor

Although he would later do so in the classroom as a matter of routine, the first time that University of Virginia Professor Albert Henry Tuttle ever presided over a large group of white southern young men was as a Union soldier on prison guard duty during the Civil War. Born in Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio in 1844, Tuttle arrived to chair a department at UVA in 1888—where he would teach for twenty-five years. At the time that he lived and worked in Charlottesville, his Union service might have set him apart from his pro-Confederate colleagues and alienated him from his environment at the University. Yet the Ohioan Tuttle embraced the historical inheritance of his setting, expressed admiration for Confederate leaders, and appears to have had no issue living among former adversaries.

Proslavery Unionism: The Anti-Republican Politics of UVA's James Shunk

The Civil War left Pennsylvania lawyer and UVA alumnus James Shunk bitter and angry. In the late 1850s, as a Federal secretary and clerk, he had championed the “permanency of the Union” and worked to hold the country together. When the war erupted, he denounced the Confederate “rebellion” and briefly enlisted in the Union’s defense. As a conservative Democrat, however, he vilified his Republican rivals, accusing them of provoking the war, defying the Constitution, and destroying the antebellum racial order. By 1865, with society transformed and slavery crumbling, Shunk feared that the Union he had hoped to save—“the Union as it was”—no longer existed.

“For the Restoration of the Union”: The Conservative Unionism of Wilson and Thomas Swann

At least sixty-nine UVA students, alumni, and professors served in the Union military during the Civil War, passing what historian Carl Degler has called the “severest test” of wartime Unionism. For southerners, in particular, service in the Union military was one of the most direct and powerful statements of enduring loyalty to the United States. Widening the scope, however, reveals dozens of other UVA alumni who affirmed their Unionism as civic and political leaders during the Civil War. Brothers Wilson and Thomas Swann, for example, were champions of the Union cause in Maryland and Pennsylvania. Wilson served as an associate member of the U.S. Sanitary Commission and a leader in Philadelphia’s Union League, while Thomas was elected as Maryland’s Unionist governor in the final months of the war.

“Equal Justice South and North”: Benjamin F. Dowell and the Radicalization of War

Like most nineteenth-century Americans, UVA’s Unionists were mainly political moderates who hoped to restore rather than radically alter the Union. Many, for example, supported emancipation as a military necessity but hoped to keep southern society essentially unchanged. For a few alumni, however, the war and its aftermath were radicalizing experiences that forced them to cast off old convictions. For men like Benjamin F. Dowell, the only way to permanently preserve the Union was to punish Confederate leaders, empower African Americans, and dramatically reconstruct the southern states. Dowell was a slaveholder’s son who became a champion of freedom—a moderate Whig who embraced Radical Reconstruction and the “eternal principles of equal rights…without regards to race, color, or sex.” His story speaks to the Civil War’s unforeseen, contested consequences and helps explain how a country of political moderates uprooted slavery and ratified the radical Reconstruction amendments.

Seeking a “Durable Peace”: The Story of UVA Republican Thomas M. Mathews

The vast majority of UVA alumni opposed Reconstruction and worked to dismantle its achievements. As political and cultural leaders, they played a major role in reasserting white supremacy and constructing the southern “Lost Cause” memory of the war. Even most UVA Unionists were political conservatives who fiercely defended the South’s racial hierarchy. Once the war was over, Unionists like William M. Fishback and James O. Broadhead called for reconciliation with former Confederates and demanded strict Black Codes to limit African American freedom. A few UVA alumni, however, embraced the Republican Party and accepted the dramatic transformations of the postwar world. During Reconstruction, southerners like Thomas M. Mathews allied with former slaves and northern Republicans to rebuild the Union and ensure a just and “durable peace.”

“Long Tried Patriotism”: The Republican Politics of UVA’s Alexander Rives

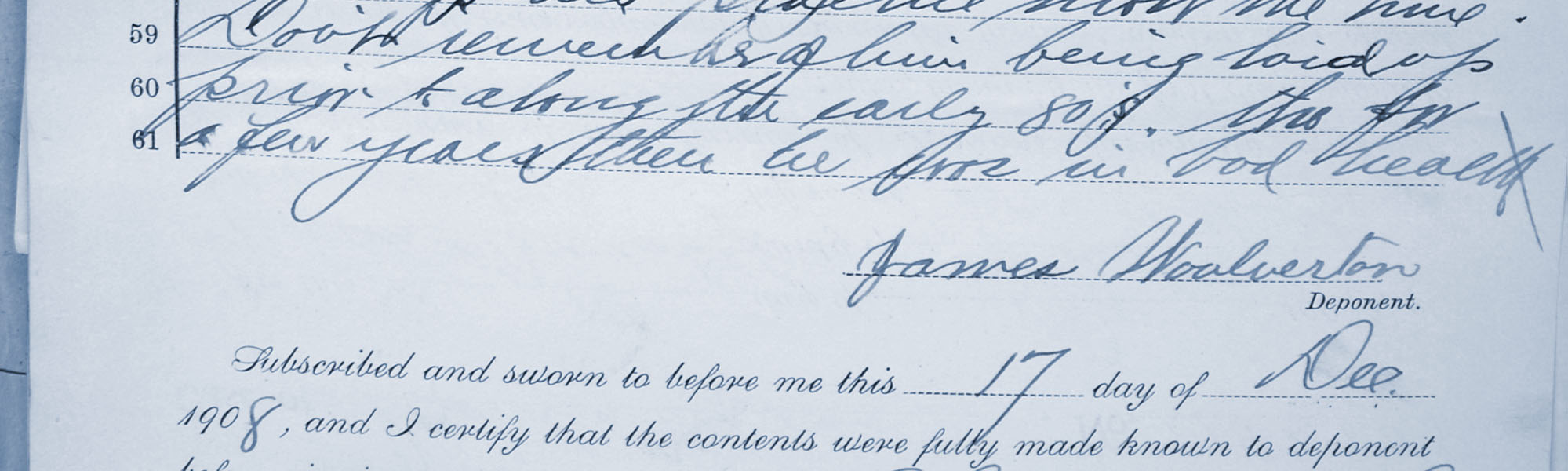

After the Civil War, the University of Virginia and its alumni played a leading role in propagating the mythology of the Lost Cause. Determined to “vindicate the character of the South,” they defended secession, valorized Confederate soldiers, and declared the postwar experiment in biracial democracy a failure. Few alumni challenged this culture of Confederate orthodoxy, and even fewer openly defended Reconstruction. Among those who did, however, was Alexander Rives, an eccentric but fiercely principled Charlottesville jurist. He was a Jacksonian Democrat who became a devoted Whig and then a pillar of the state’s Republican Party—a planter and proslavery Unionist who became a champion of Black suffrage and civil rights.