Every evening, students recalled, the hills around antebellum UVA resounded with the music of La Marseillaise, the anthem of the French Revolution. Joseph d’Alfonce, the University’s gymnastics instructor, began the call to arms in his “splendid baritone,” and soon hundreds of students’ voices filled the air. For d’Alfonce, the anthem’s promise of “cherished liberty” triumphing over tyranny carried special meaning. He had fought in one revolution and lived through another, and twice he had been forced to flee from arrest. By 1851, he had settled in Charlottesville, where he built a quieter life teaching French and gymnastics. The outbreak of Civil War, however, shattered any complacency, testing his loyalties and forcing him to flee his new home in Virginia.

As recent scholarship has shown, the nineteenth century was an era of nationalist upheaval not only in America, but also throughout the Atlantic world. Revolutions swept across Europe in 1830 and 1848, as reformers demanded self-government and constitutional freedom. In America, between 1861 and 1865, Confederates struggled for national independence while Unionists fought to preserve their nation and “nobly save…the last best hope of earth.” During those same years, Germany and Italy forged unified countries and Poland launched a year-long rebellion against the Russian Empire. These nationalist uprisings were intimately connected, as people—and ideas—travelled throughout the hemisphere. The pre-war European revolutions raised questions about nationalism, liberty, and social order that contributed to the outbreak of America’s Civil War, and European immigrants comprised more than twenty percent of the Union army. D’Alfonce, already 48 when the war began, was probably not among that number even though some would later claim he was an officer in both the Confederate and Union armies. His life, however, reflects the vibrant connections between the American Civil War era and the Atlantic world and sheds light on the challenge—faced by thousands of immigrants—to navigate their state, national, and ethnic identities in an age of revolution.[1]

Joseph Emile d’Alfonce was born in France on January 4, 1813, to a French father and a Polish mother. He received his education at the Imperial Military Academy in St. Petersburg and the military engineering school in Warsaw and by 1830 he had become an engineer lieutenant. That November, he joined Poland’s uprising against the Russian Empire, which had controlled the country since the late 1700s. Although the revolution lasted eleven months, Russia ultimately triumphed and consolidated its control over Poland. It declared Poland’s “eternal incorporation” into the Russian Empire, disbanded the Polish parliament and army, and exiled 80,000 men and women to Siberia.[2]

D’Alfonce was stripped of his rank, drafted into the Russian army, and sent to fight in the Caucasus. He regained his rank after displaying great “ability, skill, and bravery” in the war, and eventually became a professor at the Imperial Military Academy. Russian officials placed him under arrest, however, after he expressed his continued support for Polish freedom. He escaped with the help of some high-placed friends, passing through Prussia and France before immigrating to America in 1843. He returned to Paris 1848 to witness the wave of revolutions that spread across Europe that year. France overthrew its king and established a republic, but Russia quelled another Polish uprising after only two months. Russian officials soon learned that d’Alfonce had returned to Europe, and the French government reportedly warned him he would be safer in America.[3]

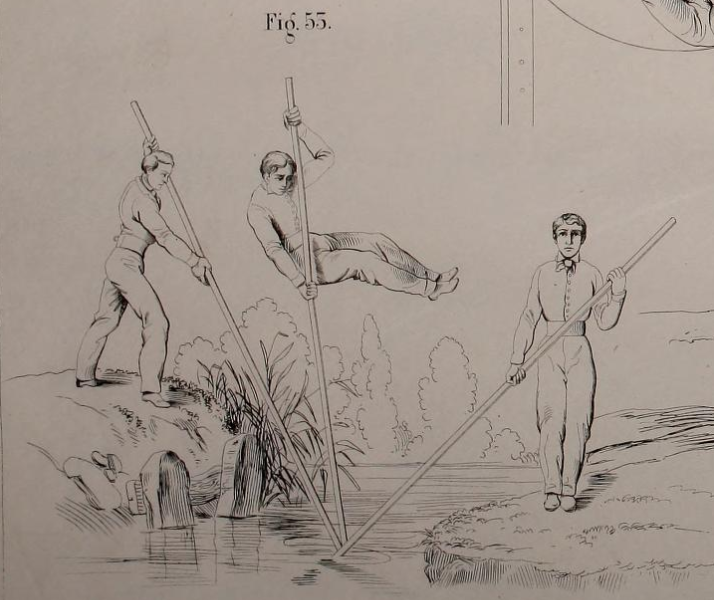

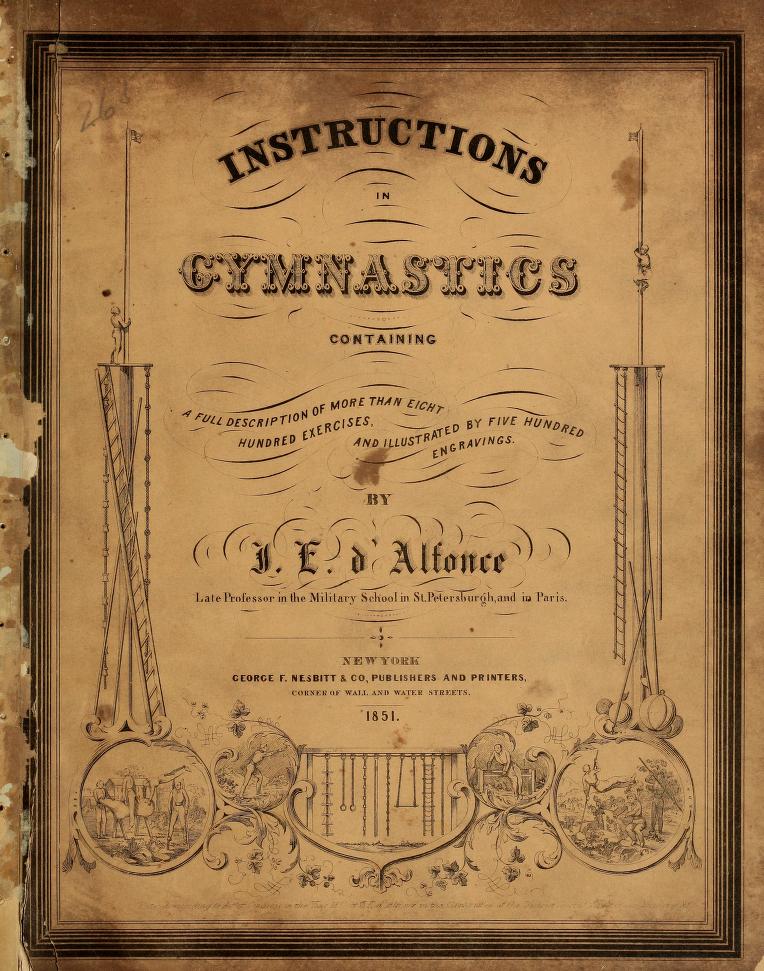

He then settled in New York, and in January 1851 he published the book Instructions in Gymnastics, a “scientific” guide to physical education. He described more than eight hundred exercises and provided two hundred hand-drawn diagrams. His military training gave him a holistic approach to education, and he argued that gymnastics helped develop the body, mind, and moral character. He believed that “civilized life” encouraged “softness and effeminacy,” which in turn led to “weakness, pain, and crime.” Physical education, however, would give children physical strength and “moral power,” teaching them how to endure and overcome life’s challenges. This training, he argued, was particularly important in America, where the “wilderness” presented a “mass of obstacles” to human settlement. Here, men needed “not only the will, but also the power necessary” to succeed, and that power could “only exist in a strong body improved by practice.” By imparting these lessons, d’Alfonce hoped to “repay a part of the debt which I owe to America for the freedom I enjoy,” and for the hospitality and friendship he had received.[4]

In March 1851, the University of Virginia hired d’Alfonce as a gymnastics instructor. He remained at UVA for the next decade, becoming a popular and well-respected teacher. Many students were initially skeptical of the “childish sport” of gymnastics, but he quickly won them over. By the late 1850s, roughly one-third of the student body was enrolled in his class, and one student praised it as the “best ticket in the University.” Embracing d’Alfonce’s holistic approach to education, a statewide magazine celebrated his gymnasium for encouraging “good fellowship” and “attention, attendance, and support.” Under his guidance, the students practiced marching, jumping, pole vaulting, fencing, and singing. D’Alfonce believed singing was an “essential part of Gymnastics,” because it strengthened the lungs and improves the “morals of men.” Decades later, alumni still recalled the “great chorus of manly voices,” as d’Alfonce and his students sang La Marseilles, Les Girondins, or other “martial strain[s].” One writer remembered the “exhilarating combination of voices” evoking the “spectacle of life, and cheerfulness, and animation.” For d’Alfonce, however, the songs must have been particularly resonant. European revolutionaries had chanted those songs in 1830 and 1848, and Les Girondins was the national anthem of the French republic.[5]

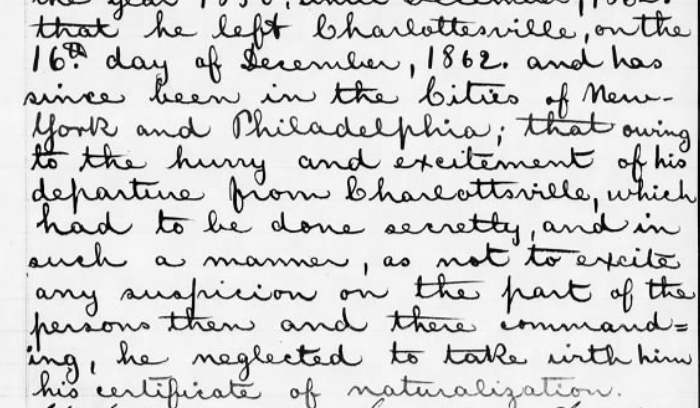

With the outbreak of Civil War, hundreds of his students enlisted in the Confederate army, and d’Alfonce may have joined them. A “biographical sketch” published twenty-five years later claims he was stationed in Richmond as a lieutenant colonel. Other post-war reports, however, describe him as a staunch Unionist. Although he made few public statements during the war, his actions reflected the complex, contested nature of wartime loyalty. In September 1861, he sang at a concert benefitting sick and wounded Confederate soldiers, performing a “Soldier’s Song” and La Marseillaise. In early 1862, he supervised construction of a steam bath for Richmond’s Chimborazo Hospital, hoping it would improve patients’ health. While in Richmond, d’Alfonce reportedly criticized the Confederate government’s treatment of its Union prisoners, and officials ordered his arrest. He quickly packed his money and belongings and fled northward on December 16, 1862. By his own account, he left the state secretly and “in such a manner as not to excite any suspicion.”[6]

By January 1863, he had reached New York City, where he applied for a passport and swore to “support, protect and defend the Constitution and Government of the United States against all enemies, whether domestic or foreign.” Long after d’Alfonce’s death, a few writers claimed he had joined the Union military, perhaps serving in the cavalry under General Philip Sheridan. In 1944, a local historian whose father had attended d’Alfonce’s gymnastics classes insisted the instructor was “northern in sympathy” and “continued to wear the Yankee blue uniform” after the war. The 1886 biographical sketch, however, places in him New York for the rest of the war, supervising the production of self-sealing envelopes. Corroborating records, if they existed, have not been found. He reenters the documentary record shortly after the war, teaching gymnastics at UVA for another year before returning to New York. He taught French and drawing at Alexander Institute for the next twenty years.[7]

D’Alfonce assumed a prominent place in New York’s Polish community and continued to champion Polish liberty in the final decades of his life. In 1869, as several European nations achieved autonomy or unification, d’Alfonce declared the “necessity of thoroughly organizing the Poles inhabiting the United States to watch the events of Europe, so that if their country should desire their services in time of need she might have their assistance.” In 1873, he served as vice president of an association seeking to establish a monument to Polish Revolutionary War hero Thaddeus Kosciuszko. City commissioners, however, refused to approve the statue, insisting that it did not “possess the artistic requirements to entitle it to a place in the Park.” In 1880, d’Alfonce served as chairman of a large meeting commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of Poland’s November Uprising. He delivered a brief address describing his own experiences in the revolution, and subsequent speakers declared the “determination on the part of the people to establish [Poland’s] undivided nationality and to rule themselves.” They insisted that “Russia could not keep Poland in subjugation much longer.” D’Alfonce died on July 19, 1886, thirty years before Poland secured its independence. In one of his final acts, he asked his friends to divide his wardrobe among the city’s needy Polish immigrants. The biographical sketch, published that November, praised his enduring commitment to Polish liberty and called him an “uncompromising foe to tyranny and oppression.”[8]

Throughout his life—and after his death—writers struggled to make sense of his national loyalties and identities. In the 1890s, one writer described him as a “Russian officer,” while another called him a “soldierly Frenchman.” Polish scholars claimed him as part of their culture’s contribution to American society, and during World War I, UVA students celebrated him as a model of French-American collaboration. One biographer insisted he had served in the Confederate army; others, that he had ridden with the Union cavalry. Each description, however, obscures as much as it reveals. D’Alfonce was a European revolutionary and an American teacher. He fought in Poland’s 1830 November Uprising and crossed the Atlantic to witness France’s 1848 revolution. He sympathized with sick and wounded Confederates as well as with Union prisoners, sang Confederate soldiers’ songs and swore to defend the U.S. government. Even in an age of nationalism, these loyalties and ideals could coexist. D’Alfonce could celebrate American freedom while spending his life dreaming of Polish independence. His life—and memory—reflected the complexities of nineteenth-century identity and revealed the rich connections between America and the broader Atlantic world.[9]

Images: (1) “Capture of the Arsenal” by Marcin Zaleski (courtesy Wikicommons); (2) Hand-drawn illustration of pole vaulting from d’Alfonce’s Instructions in Gymnastics, and (3) the book’s title page (courtesy Internet Archive); (4) Excerpt from d'Alfonce’s passport application (courtesy U.S. National Archives and Records Administration).

[1] See Don H. Doyle, The Cause of All Nations: An International History of the American Civil War (New York: Basic Books, 2015); Andre M. Fleche, The Revolution of 1861: The American Civil War in the Age of Nationalist Conflict (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012); Timothy Mason Roberts, Distant Revolutions: 1848 and the Challenge to American Exceptionalism (Charlottesville: Univ. of Virginia Press, 2009); Adam I. P. Smith, The Stormy Present: Conservatism and the Problem of Slavery in Northern Politics, 1846-1865 (Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2017); Edward Rugemer, The Problem of Emancipation: The Caribbean Roots of the American Civil War (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2008); Caitlin Fitz, Our Sister Republics: The United States in an Age of American Revolutions (New York: Liveright, 2016).

[2] Joseph Emile D’Alfonce Passport Application, 9 January 1863, in Passport Applications, 1795-1905, available from http://www.fold3.com/image/60485308; The Eastern State Journal (White Plains, NY), 2 November 1886. Russia, Prussia, and Austria partitioned the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the late 1700s. In 1815, the Congress of Vienna established the Kingdom of Poland, a semi-autonomous state ruled by the Russian tsar. While the kingdom possessed its own constitution and parliament, Russian officials began restricting Polish autonomy almost immediately. Tim Chapman, Imperial Russia, 1801-1905 (New York: Routledge, 2001), 65-66.

[3] The Eastern State Journal (White Plains, NY), 2 November 1886.

[4] Emile Del Fonce, 1850 United States Census, Canandaigua, Ontario County, New York, available from http://www.ancestry.com; The Evening Post (New York, NY), 29 January 1851; Joseph Emile D’Alfonce, Instructions in Gymnastics (New York: George F. Nesbitt & Co., 1851).

[5] Paul B. Barringer, James Mercer Garnett, and Rosewell Page, The University of Virginia: Its History, Influence, Equipment, and Characteristics (New York: Lewis Publishing Co., 1904), 140; The Richmond Enquirer, 19 October 1860; The Virginia University Magazine, Vol. III, No. 3, December 1858; The Richmond Enquirer, 4 July 1853, 10 September 1858; Staunton Spectator, 9 April 1861; D’Alfonce, Instructions in Gymnastics; “Physical Culture at the Universitiy of Virginia,” The Alumni Bulletin, Vol. I, No. 2, July 1894; Randolph Harrison McKim, A Soldier’s Recollections: Leaves from the Diary of a Young Confederate (New York: Longmans, Green and Co., 1910), available from the Jefferson’s University--Early Life Project (JUEL), http://www.juel.iath.virginia.edu; Peachy G. Harrison, “Reminiscences of Yester Student Days,” University of Virginia Alumni News, Vol. II, No. 15, April 1, 1914; The Virginia University Magazine, Vol. III, No. 3, December 1858.

[6] Christian McWhirter, Battle Hymns: The Power and Popularity of Music in the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press 2012); D’Alfonce, Instructions in Gymnastics, 8; The Richmond Enquirer, 24 September 1861; J.E. D’Alfonce, Confederate Citizens File, available from http://www.fold3.com/image/31214495.

[7] The Eastern State Journal, 2 November 1886; Joseph Emile D’Alfonce Passport Application; Nancy B. Gordon, “Records and Reminiscences of Some Schools of Albemarle,” March 1944, Harrison and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia; Ladislaus J. Siekaniec, “Poles in the U.S.: Jamestown to Appomatox [sic],” Polish American Studies, Vol. 17, No. ½ (Jan.-Jun. 1960), 13, available from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20147537; Peekskill, New York, 1866 City Directory, in “U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995,” available from http://www.ancestry.com; Catalogue of the University of Virginia, Session of 1865-’66 (Richmond: Charles H. Wynne, 1866); Monmouth Democrat (Freehold, NJ), 7 November 1867.

[8] The Sun (New York, NY), 23 January 1869; The New York Times, 10 September 1873; The New York Daily Herald, 2 June 1874; The New York Times, 30 November 1880.

[9] John S. Patton, The University of Virginia: Glimpses of its Past and Present (Lynchburg, VA: J.P. Bell, 1900), 60; Corks and Curls, Vol. 31 (1918); Ladislas John Siekaniec, The Polish Contribution to Early American Education, 1608-1865 (San Francisco: R and E Research Associates, 1976).