Most UVA Unionists—men like William Fishback, James Broadhead, and Albert Tuttle—viewed themselves as conservative men trying to preserve, rather than transform, their world. They rejected political radicalism, sought compromises to avert secession and Civil War, and often accepted post-war reconciliation with former Confederates. New York lawyer Robert Henry Shannon, however, embraced the possibilities of progress. As a Whig and a Republican, he insisted that government action could solve society’s problems and protect Americans’ liberties. He championed Radical Reconstruction, women’s suffrage, and the Greenback Labor movement—but he also sought to disenfranchise immigrants and impose Victorian morality on the working class. His political career reflects the fraught history of many nineteenth-century benevolent movements, which worked to perfect society by “reforming” the lives of its most vulnerable members.

Shannon was born in Dansville, New York, on October 27, 1816. He received an extensive education, learning Spanish, German, and Irish, and he enrolled at the University of Virginia to study law in 1836. After the faculty suspended him for gambling that November, he moved to New York City, where he quickly became active in local politics. In January 1838, he participated in a massive rally condemning the gag rule, a resolution that prevented Congress from receiving or discussing antislavery petitions. Shannon and his peers denounced the rule as a “direct and fatal attack” on the Constitution. They rejected abolitionism and expressed sympathy for southerners who felt “their institutions unjustly assailed.” Instead, they insisted that the gag rule violated White men’s liberties by denying their freedom of speech and their right of petition. These rights, they declared, ranked among the “greatest blessings and proudest prerogatives of a free people,” and they owed a duty to “our own consciences, and to the great cause of freedom” to help defend them.[1]

By 1840, Shannon joined the Whig Party, which promoted economic modernization through protective tariffs, internal improvements, and a centralized banking system. As a member of several ward-level committees, he denounced the “misrule and corruption” of the Democratic Party. Only Whig policies, he insisted, could ensure the “safety of our institutions,” the “future prosperity of our glorious government,” and the “welfare of our country.” The Whig Party’s vision of progress encompassed not only economic improvement but also moral reform. Particularly in the northeast, Whigs often supported temperance, prison reform, Sabbatarianism, and even anti-slavery sentiment. Because they equated political freedom and prosperity with middle-class Protestant morality, however, they were less tolerant of ethnic and religious diversity. They sought to “improve” society by imposing their values on immigrant and working-class families.[2]

Shannon demonstrated the complicated relationship between nativism and reform by supporting the insurgent Native American Party in 1844. The party insisted that the influx of Catholic immigrants in the 1840s would corrupt and degrade American society, and they sought to curtail immigrants’ political power by lengthening the naturalization period and restricting officeholding to native-born citizens. At a mass meeting in April 1844, Shannon thundered that Catholics had “interfere[d] with the elective franchise” and subverted American institutions. By endorsing the Native American Party, he argued, voters would protect their city from Catholic “pollution” and continue the “great work of Reformation.” Shannon blamed immigrants for the city’s crime and corruption and vowed to uphold the “wholesome laws” that “regulate our city affairs.” He served on the party’s state committee and ran for a seat in the state legislature in 1845, but he received less than nine percent of his district’s votes. The Native American movement quickly collapsed, and Shannon returned the Whig Party by the late 1840s.[3]

Shannon served as a public school commissioner in the 1850s, and he used the position to promote his moral and economic vision for society. In 1855, he delivered an address insisting that Americans lived in an “age of progress” and celebrating “[l]abor and industry” as the “foundation of our country’s prosperity.” He praised teachers for instilling innovation and civic virtue in their students, and he prayed for success in their “efforts of reform.” In 1857, the state Board of Education asked him to help improve attendance rates among working-class children. His report blamed children’s absences on the poverty, “ignorance,” and “idle habits” of immigrant families. He proposed using government action to “remedy the evil,” encouraging the state to enforce its truancy laws and help establish industrial schools. By doing so, they could improve the state’s educational system while promoting middle-class values among the urban poor. Under the law, Shannon insisted, parents “can be compelled to enter into an engagement to keep [their children] from vagrancy, and send [them] to school.” In these industrial schools, children would learn the skills they needed to compete in the nation’s diversifying economy. Together, he declared, government action and private charity could rid society of its “evils” and promote progress and prosperity.[4]

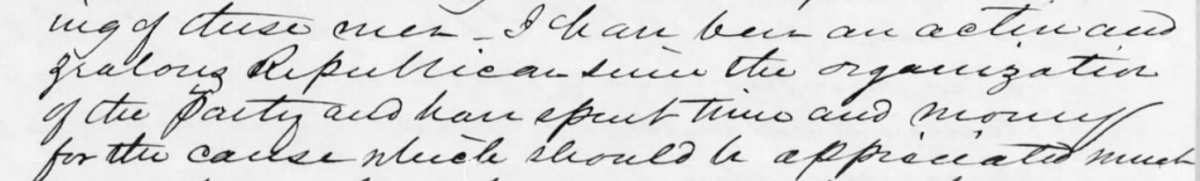

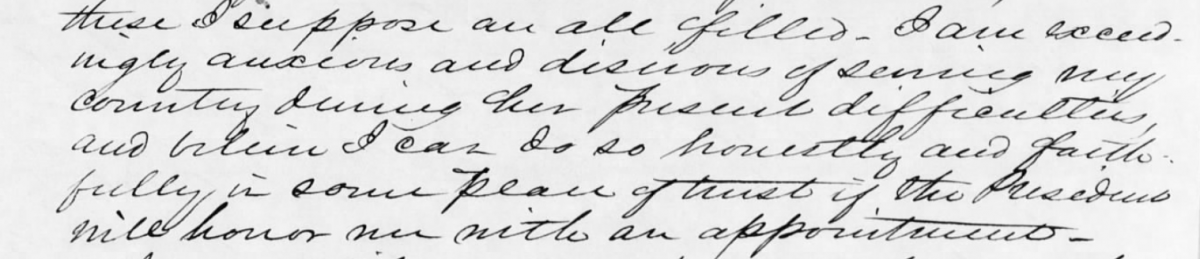

By the early 1850s, the Whig Party began unravelling, unable to contain the divisive issue of slavery’s expansion. In August 1856, Shannon travelled to Kansas, where slave-state and free-state settlers were struggling to determine slavery’s fate in the territory. Shannon encountered southern “Border Ruffians” streaming into Kansas to wage a “war of extermination against the Free State settlers,” and the experience helped galvanize his resistance. In June 1856, he had supported the nativist Know Nothing Party and endorsed its presidential candidate Millard Fillmore. By December, he had joined the nascent Republican Party. For several years, he attempted to balance these commitments, and in 1858 he ran unsuccessfully for a seat in the state legislature on a joint Republican-Know Nothing ticket. In 1860, however, he supported Abraham Lincoln’s campaign, and he later recalled that he had been an “active and zealous Republican since the organization of the party.”[5]

After Confederate soldiers attacked Fort Sumter in April 1861, Shannon joined the Union war effort almost immediately. By May, he was a captain in the “First Regiment Constitution Guard,” which quickly enrolled more than 500 men. In a series of resolutions, the officers celebrated the men who had volunteered to “sustain the government of their own creation and choice”—a government that had “cheered and gladdened the hearts of patriots and freemen throughout the world.” With America’s republican experiment in peril, they rallied their men for the “holiest war in which patriots ever engaged or heroes fell.” The state consolidated the Constitution Guard with the 40th New York Infantry and mustered them into service that summer, but Shannon was not among their ranks. In November 1861, he organized the Von Beck Canal Rangers, tasked with protecting New York’s Hudson and Delaware Canal. By January 1862, he had recruited 268 men. When the state combined the regiment with the 102nd New York Infantry shortly afterward, however, Shannon was “not continued in service.”[6]

Although he was never mustered into military service, Shannon helped raise money, recruit soldiers, and encourage support for the Union war effort. At the Cooper Institute in October 1862, he delivered a passionate address on behalf of southern Unionists. He insisted that thousands of men in the Deep South would fight against the Confederacy if the United States would only organize, arm, and encourage them. These Unionists, he argued, were “good and true, for they had firmly maintained their integrity during all their persecutions. But they need aid to carry out their intentions.” Shannon planned to travel to Washington to “endeavor to obtain relief” for these “suffering loyalists.”[7]

In March 1863, Shannon asked New York Senator Edwin D. Morgan to help him secure a more active position in the Union war effort. He was “exceedingly anxious and disirous [sic] of serving my country during the present difficulties,” and he hoped to receive an appointment as a chargé d'affaires in Europe or a judicial officer in “some one of the Rebel states.” Lincoln ultimately appointed him a U.S. Commissioner for the Eastern District of Louisiana, and he immediately began working to restore the state to the Union. He joined the state’s “Pioneer Lincoln Club” in January 1864, helped nominate Unionist Michael Hahn for governor, and delivered passionate speeches condemning the Confederacy. He championed Lincoln’s plan for Reconstruction, which readmitted states to the Union once ten percent of their 1860 voters had sworn an oath of allegiance and agreed to accept emancipation. Shannon urged Louisiana’s voters to ratify a “Free State” constitution and reclaim their place in “our glorious Union.” By doing so, he insisted, they would “set a brilliant example to their sister States” and help ensure the Union’s survival. Shannon remained firmly committed to the Republican-led war effort. He denounced “Jeff. Davis and his minions” as well as the northern Peace Democrats who opposed emancipation. He accused these men of “lov[ing] slavery better than their country” and supporting “slaveholding treason.”[8]

Shannon remained in office after the war and became an ardent defender of Reconstruction. After Lincoln’s assassination, he initially supported President Andrew Johnson, a southern Unionist who had served as military governor of Tennessee for much of the war. Shannon helped organize an “Andrew Johnson Club” in New Orleans and expressed his “confidence in the integrity, patriotism, and ability” of the new president. He trusted that Johnson would promote “universal emancipation,” fulfill Lincoln’s vision for Reconstruction, and restore “peace to the entire country.” Shannon soon became disillusioned with Johnson’s lenient policies, which effectively restored power to former Confederates and failed to protect freedpeople and White Unionists. By 1868, Shannon embraced Radical Reconstruction. He promoted measures that punished former Confederates, empowered freedpeople, and political and economically restructured the South. He and his allies insisted that only Radical Reconstruction could “secure the success of republican principles,” and they denounced their opponents as “enemies to liberty and justice.”[9]

Before Reconstruction, Shannon had expressed little sympathy for African Americans. He opposed the gag rule because it subverted White liberty, and he endorsed wartime emancipation because it strengthened the Union war effort. As U.S. commissioner, however, Shannon vigorously enforced the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which extended citizenship to “all persons born in the United States” and granted them “full and equal benefit of all laws.” He fined and imprisoned White Louisianans for beating, murdering, and terrorizing African Americans; arrested election commissioners for preventing freedmen from voting; and arraigned state judges for failing to enforce the Civil Rights Act. Supporters hailed him as a “good patriot and true Republican,” while critics of Reconstruction denounced the “infamous Commissioner” for these “persecutions and annoyances.”[10]

A District Court judge suspended Shannon from office in March 1877, and he returned to New York City, where he once again poured his efforts into social and political reform. He helped organize the New York Society for the Prevention of Crime, which sought to regulate and restrict the sale of alcohol. While members hoped to uphold “law and order,” critics accused them of being “zealous Pharisees” who spied on their neighbors and “compel men to be good in spite of their contrary inclinations.” Shannon also joined the Greenback Labor Party, an organization that opposed monopolies and supported workers’ rights and currency reform. In the early 1880s, as a member of the Anti-Monopoly movement, Shannon fought for an Interstate Commerce Commission, state and national railroad commissions, an end to convict leasing, and electoral reforms that would “defeat and punish corruption.”[11]

In 1886, a New York woman named Lucy Barber cast a ballot in the state election. Although election officials reluctantly accepted her ballot, a grand jury indicted her for “maliciously, willfully and unlawfully” voting. Shannon spoke out in her defense, arguing that neither Federal nor state law prohibited women from voting. Barber’s arrest therefore had “no legal ground” and was merely an attempt to “pervert the machinery of law to the purpose of persecution.” In April 1887, he championed women’s suffrage in front of Brooklyn’s board of election. Kansas and Wisconsin had recently granted women the right to vote in some municipal and school elections, and Shannon insisted that those experiments had been a great success. New York’s women, he assured them, would “do their duty [just] as faithfully.”[12]

For Shannon, the issue had an ethnic as well as moral dimension. By voting, he explained in October 1887, American women would infuse their morality into the political sphere and offset the “corrupting” influence of immigrants. Publicly, Shannon had devoted little attention to nativism since the late 1850s, and when he returned to it now, his focus had shifted from anti-Catholicism to anti-radicalism. He condemned the violent anarchism that had culminated in Chicago’s Haymarket Square bombing in 1886. Although the movement drew support from American- and foreign-born workers, Shannon blamed immigrants for this political and economic radicalism. He “scorned bitterly the Socialist and Nihilist voters, who knew nothing about the wants of the country” and insisted that “American-born women should be entitled to vote before foreign-born Nihilists.”[13]

Shannon continued to campaign for reform in the final years of his life. He was a manager of the American Institute, which organized exhibitions and lectures to help educate the public. He promoted civil service reform, attended the opening of New York’s “Food and Health Exposition,” and called for an investigation into police officers’ inhumane treatment of a mentally ill inmate. He died on August 13, 1896, in New York City, at the age of seventy-nine. His short obituary in The New York Times referenced his contributions to the Union cause during the Civil War and his membership in some of the city’s most prestigious social and professional organizations. It failed to record his lifetime of civic involvement—a public career that revealed the idealism and the shortcomings of nineteenth-century reform. Through government action, Shannon hoped to expand political and economic opportunity and rid society of crime and corruption. But he also sought to impose middle-class morality on the poor and to exclude immigrants from political participation. Nativism and paternalism were embedded in this conception of reform. Many nineteenth-century advocates of temperance, public school access, and penal reform shared Shannon’s conviction that, only by perfecting American society and purifying its morality could the nation fulfill the promise of this “age of progress.”[14]

Images: (1) Daily True Delta, February 13, 1864; (2 & 4) Excerpts from Robert H. Shannon to Edwin D. Morgan, March 13, 1863 (Courtesy National Archives); (3) Harper's Weekly, May 10, 1862; (5) Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, August 22, 1868.

1. James H. Smith, History of Livingston County, New York (Syracuse: D. Mason & Co., 1881), 167; Catalogue of the Officers and Students of the University of Virginia: Session of 1836-37 (Charlottesville, VA: Tompkins & Noel, 1837), available from http://www.juel.iath.virginia.edu; The Evening Post, 20 and 23 January 1838.

2. The New York Tribune, 7 April 1842, 5 October 1842, and 7 October 1842. See also Daniel Walker Howe, The Political Culture of the American Whigs (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1979) and Bruce Dorsey, Reforming Men and Women: Gender in the Antebellum City (Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 2002).

3. The New York Herald, 9 April 1844 and 12 April 1844; The Weekly Herald, 12 April 1845; Tyler Anbinder, Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1992), 11-13.

4. The New York Daily Herald, 30 June 1855; Journal of Education for Upper Canada, September 1857.

5. The New York Times, 6 September 1856; The New York Tribune, 25 December 1856; New York Daily Tribune, 3 March 1858; The New York Herald, 1 November 1858; Robert H. Shannon to Edwin D. Morgan, 13 March 1863, Letters Received by Commission Branch, 1863-1870, RG 94, NARA, available from http://www.fold3.com.

6. The New York Daily Herald, 3 May 1861; The New York Times, 8 May 1861; The New York Daily Herald, 21 May 1861.

7. The New York Daily Herald, 5 October 1862; The New York Times, 5 October 1862.

8. Robert H. Shannon to Edwin D. Morgan, 13 March 1863, Letters Received by Commission Branch, 1863, Letters Received by Commission Branch, 1863-1870, available from http://www.fold3.com; The Daily True Delta (New Orleans, LA), 21 January, 30 January, 13 February, 20 February, and 23 August 1864.

9.The Times Democrat (New Orleans, LA), 6 May 1865; The New Orleans Republican, 27 March 1868.

10. The Daily True Delta, 11 February 1864; The New Orleans Republican, 5 January, 3 May and 6 June 1868; The Natchez Democrat, 25 July 1868; The Times Picayune (New Orleans, LA), 21 July 1868.

11. The New Orleans Daily Democrat, 2 March 1877; The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 8 May 1877, 6 February 1880, and 27 April 1882; The New York Times, 21 July 1877, 12 January 1878, and 13 April 1883; The New York Tribune, 9 August 1878. Although Shannon’s suspension coincided with the end of Reconstruction, the two events were apparently unrelated. The District Court judge—Edward C. Billings—had been appointed by Republican President Ulysses S. Grant and eloquently defended Reconstruction. In 1877, Shannon detained a steamship after its captain failed to adequately pay one of the crew members. Billings rebuked Shannon for his “outrageous” decision, accused him of abusing his judicial power, and annulled his commission. See The Times-Picayune, 30 March 1877 and The New Orleans Republican, 7 April 1877.

12. The People of the State of New York v. Lucy Barber, in Reports of Cases Heard and Determined in the Supreme Court of the State of New York, Vol. LV (New York: Banks & Brothers, 1888); The Sun (New York, NY), 10 January 1887; The Springville Journal (Springville, NY), 21 January 1887; The Buffalo Commercial (Buffalo, NY), 6 April 1887; The Central News (Perkasie, PA), 10 November 1887.

13. The Buffalo Commercial (Buffalo, NY), 6 April 1887.

14. The New York Times, 15 August 1896.