At least sixty-nine UVA students, alumni, and professors served in the Union military during the Civil War, passing what historian Carl Degler has called the “severest test” of wartime Unionism. For southerners, in particular, service in the Union military was one of the most direct and powerful statements of enduring loyalty to the United States. Widening the scope, however, reveals dozens of other UVA alumni who affirmed their Unionism as civic and political leaders during the Civil War. Brothers Wilson and Thomas Swann, for example, were champions of the Union cause in Maryland and Pennsylvania. Wilson served as an associate member of the U.S. Sanitary Commission and a leader in Philadelphia’s Union League, while Thomas was elected as Maryland’s Unionist governor in the final months of the war.[1]

Together, their lives reflect the flexibility and fragility of the war’s Unionist coalition and demonstrate the fundamental conservatism of most white 19th-century Americans. Both men were political moderates and former plantation owners, and Thomas once viewed slavery as an essential “condition of our compact of Union.” They rallied behind the Republican-led war effort, giving speeches, donating money, and encouraging enlistment, and they ultimately accepted emancipation as a military necessary. Their conservatism, however, remained unshaken, and after the war, they supported Andrew Johnson’s lenient plan for Reconstruction. As Congressional Republicans fought for Black suffrage and civil rights, the brothers abandoned the Unionist coalition; Thomas joined the Democratic Party, while Wilson retired from politics altogether. Their stories mirror those of countless southern Unionists, helping explain the Union’s survival but also the failure of Reconstruction.[2]

Wilson Cary Swann was born on August 3, 1806, in Alexandria, Virginia, and his brother Thomas Swann followed on February 3, 1809. Their father Thomas Swann was the U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia, and their mother Jane Byrd Page was descended from one of the First Families of Virginia. The brothers received their early education in Washington, D.C., before enrolling at the University of Virginia together in 1826. Among their classmates was Charles B. Calvert, who later served as a Unionist congressman from Maryland during the Civil War. Wilson studied medicine at UVA for two years, while Thomas spent three years studying moral philosophy and ancient languages. Thomas was an average student, and the faculty repeatedly admonished him for drinking, gambling, and attending “disorderly” parties. Wilson, however, earned a distinguished place in the student body. In July 1826, when students gathered at the Rotunda to mourn the death of Thomas Jefferson, they selected Wilson as the meeting’s secretary.[3]

Wilson earned his medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania in 1830 before returning to Virginia. When their father died in 1840, Wilson inherited Black Walnut Island in the Potomac River, and he later expanded the plantation by purchasing land on the Virginia and Maryland shores. On October 12, 1847, he married Maria Elizabeth Bell, the daughter of a Philadelphia stockbroker and “one of the greatest belles [of] that day.” For the next few years, they divided their time between Pennsylvania and Virginia. When Maria’s health began to decline, Wilson sold his plantation and moved permanently to Philadelphia. Before doing so, he freed his forty slaves and arranged for them to move to New Jersey, where he reportedly paid their rent and funded the children’s education. As such, he became one of the only UVA Unionists to emancipate his slaves before the Civil War. While in Philadelphia, Wilson earned a reputation as a “gentleman at large,” and he used his fortune to patronize the arts and promote civic reform.[4]

Thomas, meanwhile, devoted his life to business and politics. After leaving UVA, he studied law under his father and earned admission to the Virginia bar. He moved to Baltimore, Maryland, in 1834, and on May 19, he married Elizabeth Gilmer Sherlock, the daughter of an “English gentleman.” Thomas spent the next two decades as a railroad executive, becoming president of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad in 1848. His life often intersected with that of classmate Charles Calvert: the two men both joined the elite Baltimore Farmer’s Club, both served as delegates to the 1853 Southern Commercial Convention, and both sought the Whig Party’s gubernatorial nomination in 1853. Thomas came close to securing the nomination, but he lost out to Congressman Richard Bowie.[5]

When the Whig Party collapsed in the mid-1850s, Thomas joined the nativist Know Nothing Party. In 1856, he became mayor of Baltimore in one of the city’s bloodiest and most corrupt elections. Partisan gangs battled in the streets, and Know Nothing voters used violence and intimidation to keep immigrants from the polls. In 1857, Democratic Governor Thomas Ligon ordered thousands of militiamen to maintain order in Baltimore ahead of the city’s municipal elections. Know Nothings, led by Thomas, accused the governor of subverting local authority and trying to engineer a Democratic victory. Congressman Henry Winter Davis—a fellow Know Nothing partisan and UVA Unionist—praised Swann’s “indomitable firmness” and urged him not to yield. Ligon ultimately relented, and Know Nothings violently maintained power in the city until 1860.[6]

As mayor, Thomas championed civic reform. He modernized the police and fire departments, installed street-car and water-works systems, and organized an expansive city park. Racism and nativism, however, often guided the logic of these reforms. He kept the city’s parks segregated and filled the police force with Know Nothings, who sometimes refused to protect the city’s immigrants. Later, when an oyster crisis in New England caused Maryland’s local industry to surge, Swann supported a racist licensing law designed to push Black men out of the oyster trade. The new law empowered “white men” to “summon [a] posse comitatus” and arrest anyone suspected of catching oysters without a license.[7]

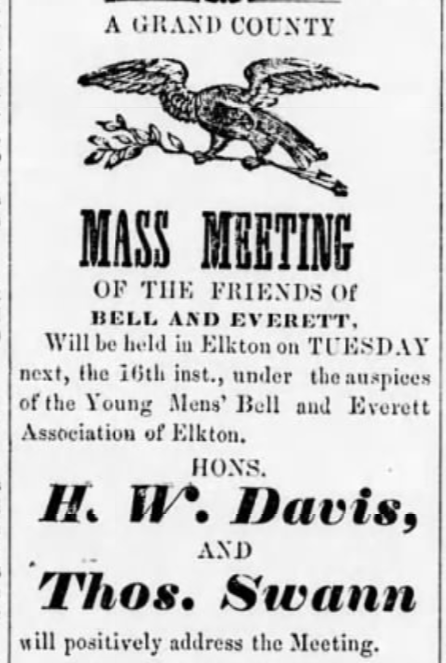

In April 1860, Thomas helped engineer a fusion between Baltimore’s Know Nothing Party and the Constitutional Union Party. He attended that month’s Constitutional Unionist state convention, and when a delegation of Know Nothings asked to join the meeting, Thomas rose in support. “For the past three years,” he explained, he had “been working incessantly against the [Democratic Party],” and he hoped that Know Nothings and Constitutional Unionists could form a “great Opposition” against their “common enemy.” He supported John Bell in the 1860 presidential election—drafting public letters, attending party rallies, and delivering “forcible addresses” for the Constitutional Union Party. He campaigned alongside Henry Winter Davis, who also viewed the new party as the best way to defeat the Democrats and preserve the Union.[8]

When the Civil War erupted, the Swann brothers threw themselves into the Union war effort. Wilson purchased a $1,000 bond to help fund the war and contributed to the Citizens’ Bounty Fund to encourage enlistment. He served as an associate member of the U.S. Sanitary Commission and was one of the first members of the Union Club of Philadelphia, a patriotic social organization. Wilson hosted the Club’s sixth meeting at his Walnut Street house on December 20, 1862. The Club soon outgrew these small domestic gatherings, and members reorganized as the Union League in order to play a more active role in the war effort. Wilson signed the League’s Articles of Association at its first meeting on January 8, 1863. Members swore “unqualified loyalty” to the federal government and urged Lincoln to “suppress the Rebellion” at all costs. They printed patriotic literature, helped recruit “nine effective regiments,” and provided work and legal assistance for disabled soldiers. In 1863, Wilson helped organize a grand July 4th celebration at Independence Hall, meant to declare the “indivisibility of the American Union” and the “inflexible purpose of the American people…to subdue the enemies of the Union.”[9]

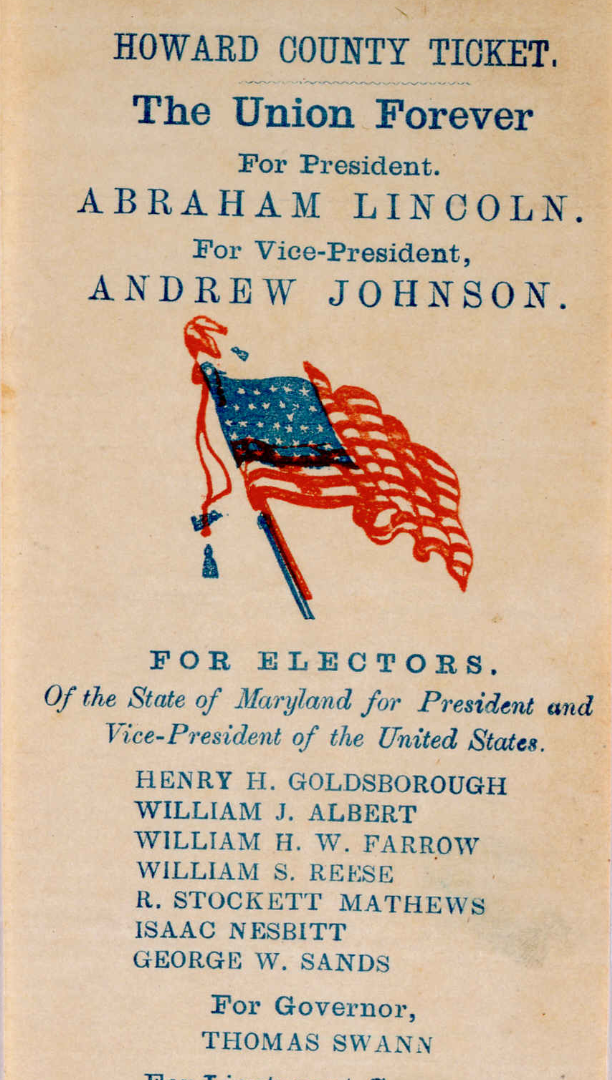

Thomas, meanwhile, served as president of Maryland’s Union State Central Committee. As a proslavery Unionist, he hoped that President Abraham Lincoln would wage war “for the restoration of the Union, and not for the overthrow of slavery.” He considered slavery a fundamental “condition of our compact of Union,” insisting the southern states had only ratified the Constitution because they believed it would sanction and protect their “peculiar institution.” By March 1863, however, Thomas recognized that emancipation was necessary to win the war and ensure the Union’s long-term survival. Lincoln had framed the Emancipation Proclamation as a military necessary, in part, to appeal to Border State conservatives like Thomas. Throughout the war, Lincoln encouraged southern states to abolish slavery themselves, and Thomas urged Maryland voters to give the president’s “invitation” their “calm and unprejudiced consideration.” In 1864, as president of the Union State Central Committee, Thomas helped spearhead the movement to amend Maryland’s constitution and abolish slavery. He also vocally defended the Lincoln administration, and when the president won reelection in November 1864, Thomas wrote to offer his “sincere congratulations.” That same year, Maryland voters elected Thomas governor on a platform of Unconditional Unionism, and he formally took office on January 11, 1865.[10]

During the Civil War, Republicans, War Democrats, and loyal southerners formed a broad Unionist coalition committed to defeating the Confederacy and preserving the Union. The Swann brothers eagerly joined its ranks, and after the war, they hoped the Union Party would survive as a permanent conservative organization. Wilson, for example, served as president of Philadelphia’s Constitutional Union Association, which he viewed as the “only Conservative Organization in this city outside of the Democratic Party.” Thomas, similarly, served as president of a “grand Union mass meeting” in Baltimore in 1866, where the city’s “conservative masses” waved banners proclaiming, “No affiliation with rebels or radicals.” President Andrew Johnson personified their political ideals, and the brothers championed his lenient plan for Reconstruction. In a speech in 1866, Thomas declared that he wholeheartedly “endorse[d] the reconstruction policy of President Johnson,” and the following year, Wilson “retain[ed] an abiding and unshaken faith in the [president’s] firmness, wisdom, and integrity.”[11]

Like Johnson, Thomas advocated sectional reconciliation at the cost of racial justice. In his inaugural address, he urged Maryland voters to “lay aside the animosities of the past” and “come together once more in a spirit of conciliation and harmony.” He later denounced Radical Reconstruction as a “war of persecution,” insisting it would destabilize the country and transform the government into an “absolute, consolidated oligarchy.” Thomas accepted emancipation as a military necessity, but he refused to go further. He fiercely opposed Black suffrage and civil rights, insisting the “two races cannot coexist on terms of equality.” At a Union Party meeting in 1866, Thomas argued that “forced negro suffrage and negro equality will destroy the State of Maryland” and provoke a deadly “war of races.” Thomas partnered with Johnson to keep Radical Republicans from gaining power in Maryland, allowing some former Confederates to vote and imposing harsh restrictions on the state’s Black population. Once again, Thomas couched these racist policies in the language of order and reform, warning that “mobs of Radicals from other States [were] rushing to Baltimore” to provoke political chaos.[12]

The Unionist coalition crumbled during Reconstruction, as many conservatives refused to extend political rights to African Americans. As their hopes for a conservative Union Party faltered, many southern Unionists—like Thomas Swann—ultimately joined the Democratic Party and fought to unravel the achievements of Reconstruction. In 1869, when Thomas’s term as governor expired, Baltimore voters elected him to Congress, where he spent the next decade railing against Reconstruction and civil rights. Wilson resigned from the Union League on December 18, 1866, and retired from politics altogether after 1867. He committed the rest of his life to civic reform. He served as president of the Pennsylvania Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and co-founded the Philadelphia Fountain Society, which built drinking fountains throughout the city to “promote temperance and relieve animal suffering.” Wilson died in Philadelphia on March 21, 1876, and Thomas passed away seven years later, on July 24, 1883, in Leesburg, Virginia.[13]

The stories of the Swann brothers speak to the strengths and the limitations of the Civil War’s Unionist coalition. The Union was a powerful ideal for 19th-century Americans, offering political liberty and economic opportunity for all white men. When secession threatened to unravel the republic, millions of Americans—Republicans, War Democrats, and southern Unionists alike—banded together to defend it. Many conservatives, including Wilson and Thomas Swann, eventually accepted radical measures like emancipation in order to win the war. With victory assured, however, these conservatives hoped to preserve as much of the old social order as possible. Unable to imagine a peaceful, multiracial society, they severed ties with Radical Republicans and fought against Black political equality. By the late 1860s, the war’s Unionist coalition had collapsed as men like Wilson and Thomas Swann chose to “lay aside the animosities of the past” rather than embrace the radical possibilities of Reconstruction.[14]

Images: (1) Thomas Swann (courtey Wikicommons); (2) "Mass Meeting of the Friendds of Bell and Everett" (printed in the Cecil Whig (Cecil County, MD), October 13, 1860); (3) "Howard County Ticket" (couresty Library of Congress); (4) Swann Memorial Fountain, Philadelphia, PA (courtesy Wikicommons).

[1] Carl N. Degler, The Other South: Southern Dissenters in The Nineteenth Century (New York: Harper & Row, 1974), 174.

[2] See Adam I. P. Smith, The Stormy Present: Conservatism and the Problem of Slavery in Northern Politics, 1846-1865 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2017); Jack Furniss, “States of the Union: The Rise and Fall of the Political Center in the Civil War North,” (PhD diss., University of Virginia, 2018); Matthew Mason, Apostle of Union: A Political Biography of Edward Everett (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016).

[3] Minutes of the Faculty of the University of Virginia, Session 2, 1826, available from Jefferson’s University: The Early Life, http://juel.iath.virginia.edu/node/343?doc=/juel_display/faculty-minutes/Sessions/session-002; The Richmond Enquirer, 11 July 1826. At the time of the brothers’ birth, Alexandria was still a part of the District of Columbia. Congress returned it to Virginia in 1846.

[4] The Baltimore Sun, 31 July 1849; “Wilson C, Swann, M.D.,” The Biographical Encyclopedia of Pennsylvania of the Nineteenth Century (Philadelphia: Galaxy Publishing Company, 1874), 102-103; Pennsylvania and New Jersey Church and Town Records, 1669-2013, available from http://www.ancestry.com; The Baltimore Sun, 31 July 1849. UVA alumnus Henry Winter Davis and Professor William Barton Rogers may also have freed their slaves before the war, but the details are unclear.

[5] Warfield, The Founders of Anne Arundel and Howard Counties, 285-287; Crenson, Baltimore, 209-212; The Baltimore Sun, 16 May 1853 and 2 September 1853.

[6] Warfield, The Founders of Anne Arundel and Howard Counties, 285-287; Crenson, Baltimore, 209-212; Nathania A. Branch Miles, Monday M. Miles, and Ryan J. Quick, Prince George’s County and the Civil War: Life on the Border (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2013); Bernard Christian Steiner, Life of Henry Winter Davis (Baltimore: John Murphy Company, 1916), 113.

[7] Joshua Dorsey Warfield, The Founders of Anne Arundel and Howard Counties, Maryland (Baltimore: Kohn & Pollock, 1905), 285-287; Carl T. Hyden and Thoedore F. Sheckels, Publics Places: Sites of Political Communication (London: Lexington Books, 2016), 144; Supplement to the Maryland Code, Containing the Acts of the General Assembly, Passed at the Session of 1868 (Baltimore: John Murphy & Co., 1868), 155.

[8] The Daily Exchange, 20 April 1860; The Cecil Whig, 29 September 1860.

[9] The Cecil Whig, 20 October 1860; The (Baltimore) Daily Exchange, 2 November 1860; The Philadelphia Inquirer, 28 September 1861, 11 August 1862, 10 June 1863, and 2 May 1865; O.H. Leigh, Chronicle of the Union League of Philadelphia, 1862 to 1902 (Philadelphia: n.p., 1902); The Union Club/Dreer Collection, 1863-1906, The Union League Legacy Foundation, Philadelphia, PA.

[10] The Cecil Whig, 14 March 1863; The Baltimore Sun, 29 September 1864, 11 October 1864, and 12 January 1865; The (Bel Air) Aegis and Intelligencer, 21 October 1864; The (Lancaster, PA) Inquirer, 26 January 1864; Thomas Swann to Abraham Lincoln, 12 November 1864, Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress; Christian G. Samito, Lincoln and the Thirteenth Amendment (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 28). See also James Oakes, The Crooked Path to Abolition: Abraham Lincoln and the Antislavery Constitution (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2021).

[11] Wilson C. Swann and William H. Holloway to Andrew Johnson, 1 February 1868, Papers of Andrew Johnson, Vol/ 13: September 1867-March 1868, ed. Paul H. Bergeron (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1996); The (Philadelphia) Evening Telegraph, 21 November 1867; The Baltimore Sun, 22 June 1866. In 1865, Thomas Swann delivered a eulogy for fellow UVA Unionist Henry Winter Davis. Although the two men had worked together to keep Maryland in the Union, they had differed on “questions of national and State politics” during the war. Davis became a Radical Republican who championed emancipation, civil rights, and Black suffrage. Swann, however, remained a conservative and hoped to preserve much of the antebellum racial order. Nonetheless, Swann praised Davis as a “brilliant orator, firm and decided in all his impulses” and acknowledged that “few of our public men in the country have built up a greater reputation for cultivated genius.” See Steiner, Life of Henry Winter Davis, 373-374.

[12] Jean H. Baker, “The End of Reconstruction,” in Encyclopedia of the Reconstruction Era, Vol. 1: A-L, ed. Richard Zuczek (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2006), 396-397; The Cecil Whig, 14 March 1863; The Baltimore Sun, 12 January 1865 and 22 June 1866; Douglas R. Egerton, The Wars of Reconstruction: The Brief, Violent History of America’s Most Progressive Era (New York: Bloomsbury USA, 2014), 226.

[13] The Evening Telegraph, 24 June 1867; The Aegis and Intelligencer, 21 January 1870; The Philadelphia Inquirer, 22 March 1876; The Cecil Whig, 28 July 1883; “Wilson Cary Swann,” Philadelphia Public Art (https://www.philart.net/person/Wilson_Cary_Swann/148.html); Union League Membership Collection, The Union League Legacy Foundation.

[14] The Baltimore Sun, 22 June 1866.