In the years preceding the Civil War, White Virginian society was highly stratified and deeply invested in the preservation of its slaveholding tradition. Slavery was the foundation for nearly all of the state’s agricultural, industrial, and economic growth. Slaves living on plantations dealt with severe working conditions and insufficient rations, and the threat of southern sale or westward movement constantly hung over them. Free Virginians of color faced similar instability, as their right to reside in the state was frequently called into question. These challenges led to a way of life characterized by continuous movement and fluctuating legal status. Black Virginians, whether enslaved or free, had to find ways to navigate a social and political system intent on maintaining their subordination. According to Ervin L. Jordan, Jr., Black Virginians were the majority in Albemarle County, comprising fifty-four percent of the population in 1860. Many Albemarle-born African Americans went on to serve in the war, enlisting in the United States Colored Troops (USCT). Their service and pension records allow us to draw out information about their lives in and out of service—painting a fuller picture of the ways Black Virginians loved, labored, and endured in the years before the Civil War.

Virginia’s economy was dependent on slavery in the prewar years. Tobacco and grain, the state’s major cash crops, were generally grown on plantations using slave labor. William Page and Peter Churchwell, both of whom would go onto enlist in infantry regiments of the USCT, were enslaved on plantations near Charlottesville in the years before the war. Henry Kettell—alternatively listed as Henry Kettel, Williams, Catton, or Kachton in various records—lived thirteen miles away from the city where he worked on his master's farm. The daily lives of these men and their families would have centered primarily around agricultural labor, excepting Page, who worked in the main house of the Blenheim Estate as a waiter. Most slaves on plantations received only two meals a day, usually comprised of cornmeal, grits, molasses, and pork. Some grew vegetables, fished, and trapped small game animals to add to their repetitive and insufficient diets, but malnutrition frequently reared its head in the form of scurvy, cholera, and protein deficiencies. In addition to these illnesses, pneumonia, smallpox, and yellow fever were prevalent. Occasionally doctors would be called to plantations to treat infirmed slaves, but for the most part they developed ways to treat themselves using a skillful combination of folk medicine and medicinal herbs.

Enslaved Virginians also played a significant role in the state’s rapid industrialization. Virginia amassed more factories than any other southern state in the early nineteenth century, and these factories were primarily powered by rented slave labor. Slaves worked mostly in tobacco processing plants, but they also contributed to flour and textile mills as well as coal mines. Increased demand for urban laborers led to a growth in the number of slaves living in cities, which is consistent with an overall increase in Virginia’s slave population. As abolitionist sentiments progressed in the northern United States and modernization threw the moral complications of slavery into sharper relief, the peculiar institution continued to grow dramatically in the South. From 1800 to 1860, the number of slaves living in Virginia increased by nearly 150,000.

This growth in slave population is even more noteworthy considering the numerous forced migrations of slaves out of the state during the same time period. Virginia emerged as a dominant supplier in the domestic slave trade after Congress abolished the African slave trade in 1807, fulfilling the persistent demand for cheap labor in the Deep South. Between 1830 and 1860, 280,000 Virginian slaves were traded out of the state. The threat of being sold, split from their families, and torn from the only home they had ever known loomed over enslaved Virginians. While it is not known how many Albemarle slaves were split from their families by the slave trade, the enlistment and pension records of soldiers from the county indicated that dozens of them suffered this fate. In one particularly heart-breaking instance, a man named Thornton Davis claimed to have been sold and separated from his family when he was only eighteen-months.

The enslaved also faced the possibility of being moved westward with their owners’ families. As the incorporation of new states and territories such as Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Kentucky spurred land rushes, many Virginian slaveowners began to stake their claim on the western frontier. Often, they brought their slaves with them, as was the case with the Carter family. John Coles Carter, married to Thomas Jefferson’s granddaughter Ellen Monroe (Bankhead) Carter, owned 103 slaves before he moved out to Missouri in 1852. Many of these slaves, as well as those owned by his son, John Jr., were forced to accompany the family’s migration in order to work the 1,500 acres Carter had inherited in Pike and Lincoln Counties. At least twenty-three Albemarle-born men included in this migration would go on to serve in Missouri regiments of the USCT, many enlisting under the surname Carter. These men exemplify the complicated, geographically spaced-out paths many Virginian-born African Americans took towards enlistment in the Union Army.

The status of free Black Virginians during this time period was similarly complex. A law passed in 1806 required all manumitted slaves to leave the state within a year of obtaining their freedom. Though some were afforded a small amount of security through relationships with White members of their communities, this law largely destabilized the lives of free Virginians of color. Enforcement became even stricter in the wake of Nat Turner’s 1831 slave rebellion, which stirred White fears of Black insurrection. At any moment, free Black Virginians could be questioned, harassed, re-enslaved, or forced to leave the state. Many of them did move out of Virginia soon after being freed, including John Allen, George W. Lewis, and James H. Garland. Allen and Lewis were former slaves of Charles Everett, an Albemarle doctor who died in 1848 and whose will stipulated that his slaves be freed and moved together to form a community, called “Pandenarium,” in Mercer County, Pennsylvania. Sixty-three newly freed Black Virginians made their way to Pandenarium in 1854, and upon arrival each family received 1,000 dollars and the deed to two acres of land. Though Garland was not listed as one of Everett’s former slaves, he likely moved with this group to Pennsylvania, as he was born in Albemarle County and lived in Pandenarium before the war. Garland, Allen, and Lewis would go on to enlist together in the 127th USCT Infantry Regiment. In a similar story, John Reed was one of fifty slaves who were moved to Ohio, freed, and given land by their former owner, John Fowles. Born in Albemarle County in approximately 1844, Reed would have been only about eight years old when he left Virginia for Ohio.

Though many manumitted slaves were forced out by Virginia law during this time, there was still a sizeable community of free people of color in the state. This population slowly but steadily increased in the first half of the nineteenth century, and by 1860 there were more than 58,000 free African Americans living in Virginia. Two 1833 Albemarle County censuses give insight into the occupations held by the 452 free Black men and women who were surveyed. As Jordan notes, the largest numbers worked in carpentry, farming, housekeeping, and washing. Several of them were also employed in skilled trades as blacksmiths, seamstresses, weavers, and shoemakers. James T. S. Taylor and Nimrod Eaves were both free and living in Albemarle County before the war, and they led similar lives to those who had been surveyed in 1833. Taylor was born free in Virginia in 1840. He became a shoemaker, like his father, and lived in Charlottesville after moving there with his family in the 1850s. Eaves lived in Boonesville, Albemarle County, in the home of a Rice Keller and worked as a laborer and farmhand. These men, their families, and many like them were able to establish somewhat secure livelihoods despite the turbulent racial hierarchy in which they found themselves enmeshed. As the nineteenth century progressed, though, abolition became a more prevalent political issue. The abolitionist John Brown, along with twenty-two others, raided Harper’s Ferry in October of 1859, exacerbating the paranoia of White Virginians. Their fears manifested again in increasingly harsh treatment of free Black Virginians, who represented an open contradiction to the racial hierarchy at the heart of the state’s slaveholding tradition.

As the nation moved closer to war, tensions between the North and South continued to flare with increasing frequency. Abraham Lincoln was elected president in November 1860, and secession began to sweep through the slaveholding states. Virginia faced a critical choice: stay in the Union—and threaten a way of life inextricably dependent on slavery—or join the belligerents. At first, apprehension about leaving seemed to dominate, with Virginians voting two-to-one in opposition of secession on April 4, 1861. The governor of Virginia, John Letcher, was strongly in favor of remaining in the Union, as were a large number of upper-class elites in urban areas and across the state. Many were not only reluctant to leave the security of the Union, but actively offended by the treachery of secession. After the firing on Fort Sumter on April 12 and Lincoln’s successive call to arms, though, this resolve was shaken. White Virginians took to the streets in displays of enraged Southern pride, and less ardent Unionists shifted their stance in response to the federal aggression. Delegates officially voted to secede on April 17.

As the state prepared to fight for the Confederacy, Black Virginians, however, prepared to resist. Reported instances of small-scale slave revolts had been increasing across Virginia in the year before the state seceded, some of which were likely fabricated or exaggerated by paranoid slaveholders. Still, some Black Virginians did commit instances of arson, theft, or escape, marking their opposition to the Confederate cause clearly and urgently. Though they were often denied access to reliable news, word spread of Lincoln’s election and the approaching conflict. The impending Civil War loomed over Black Virginians, representing the possibility of a new way of life for many who escaped to freedom in Union lines or hoped to do so as the war dragged on.

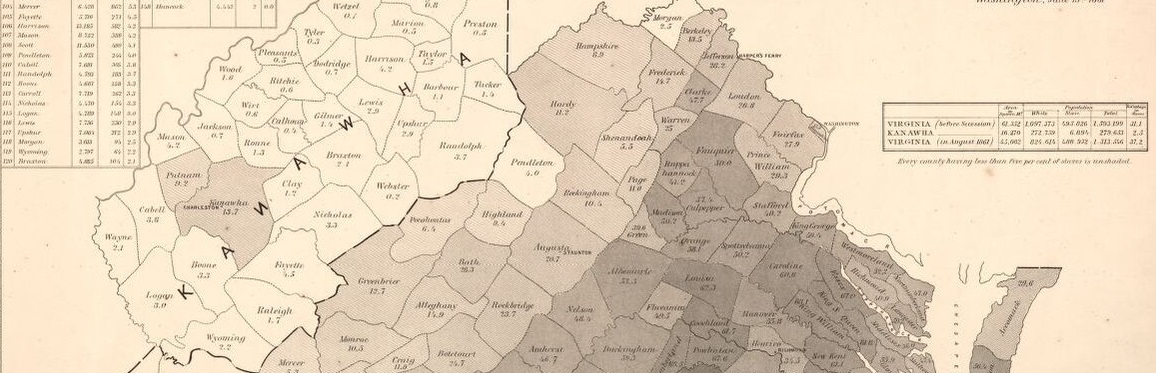

Image: Map of Virginia: Showing the Distribution of its Slave Population from the Census of 1860 (courtesy Library of Congress).

Compiled Service Records for Peter Churchwell, Nimrod Eaves, Henry Kettell, William Page, John Reed, and James T.S. Taylor, RG 94, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Accessed through Fold3 (https://www.fold3.com/browse/273/); Pension records for Peter Churchwell, Thornton Davis, Nimrod Eaves, Henry Kettell, William Page, John Reed, and James T.S. Taylor, RG 15, National Archives and Records Administration; Kirt Von Daacke, Freedom Has a Face: Race, Identity, and Community in Jefferson’s Virginia, (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2012); Jane Diamond, “Patriots in Pandenarium,” http://naucenter.as.virginia.edu/diamond-pandenarium-usct; Ervin L. Jordan, Jr., Black Confederates and Afro-Yankees in Civil War Virginia, (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1995); Ervin L. Jordan, Jr., “‘A Just and True Account:’" Two 1833 Parish Censuses of Albemarle County Free Blacks," The Magazine of Albemarle County History 53 (1995): 114-39; Peter Kolchin, American Slavery, 1619-1877, (New York, NY: Hill and Wang, 2003); William A. Link, Roots of Secession: Slavery and Politics in Antebellum Virginia, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003); Charles L. Perdue, Thomas E. Barden, and Robert K. Phillips, eds., Weevils in the Wheat: Interviews with Virginia Ex-slaves, (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1976); Midori Takagi, Rearing Wolves to Our Own Destruction: Slavery in Richmond, Virginia, 1782-1865, (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999); Elizabeth R. Varon, “From Carter’s Mountain to Morganza Bend: A U.S.C.T. Odyssey (Part I),” http://naucenter.as.virginia.edu/blog-page/406.