Miller's Hotel / Hotel Eggleston

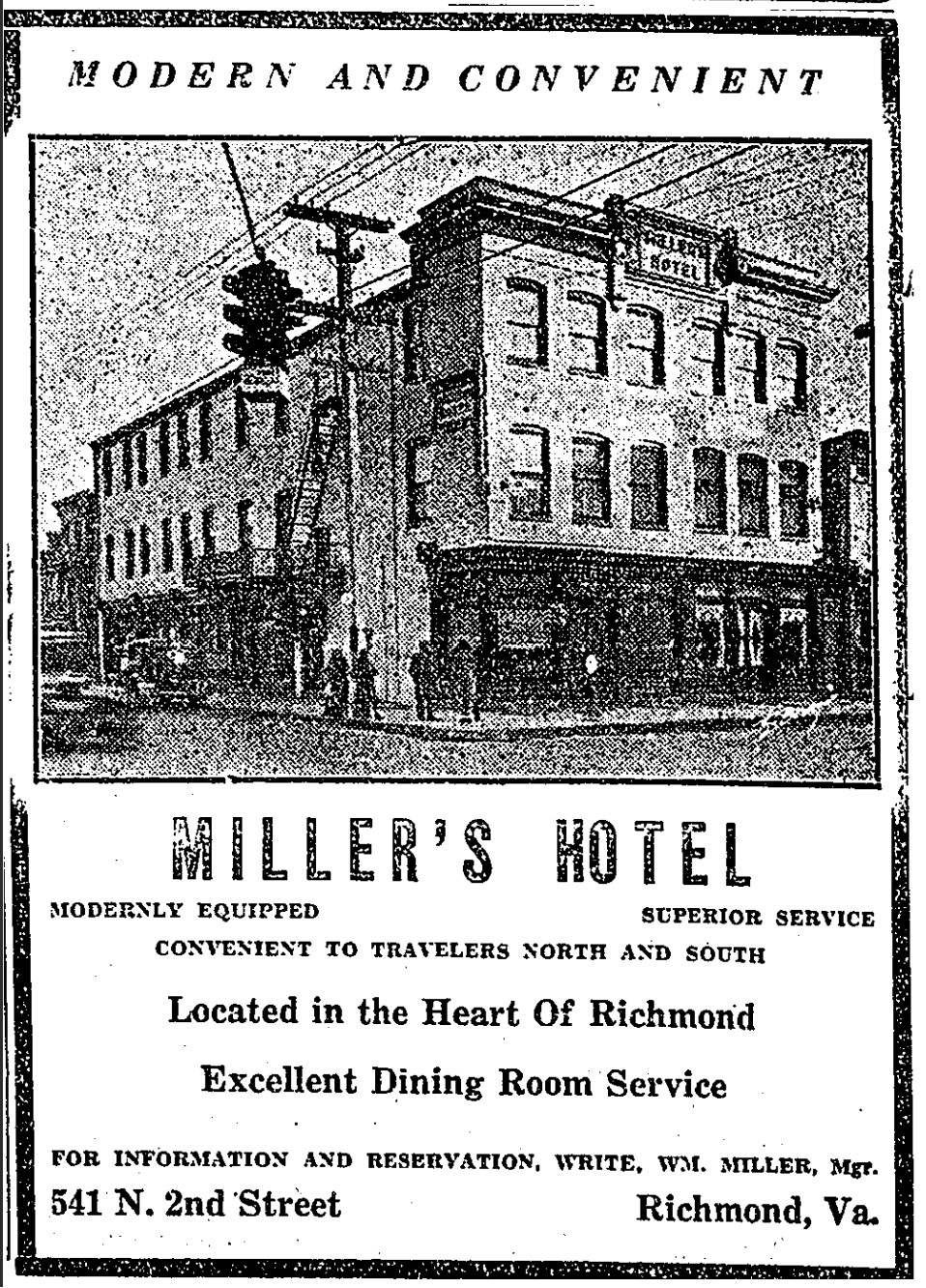

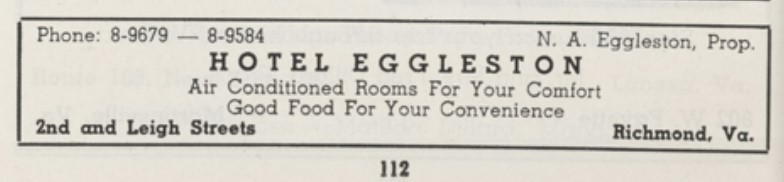

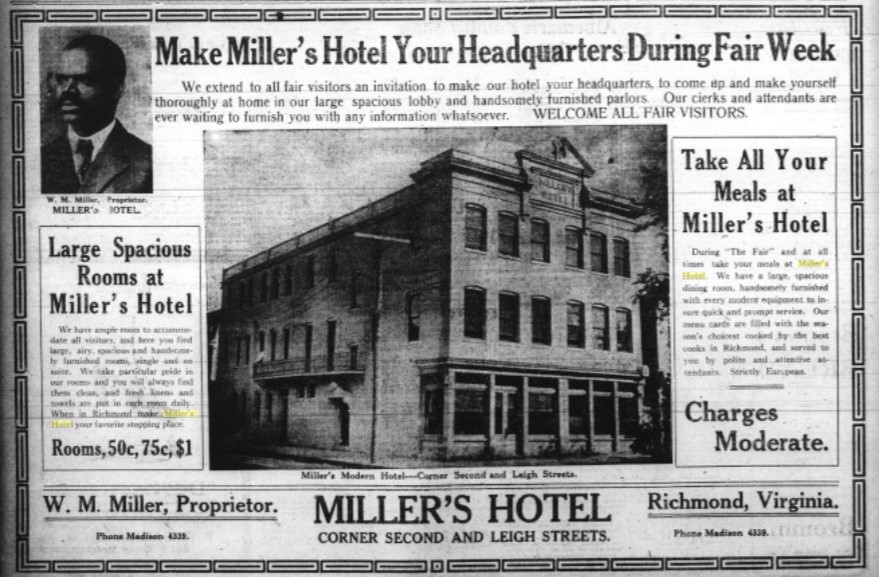

Miller's Hotel ad, with an image of proprietor William M. "Buck" Miller, in The News Leader, October 27, 1910.

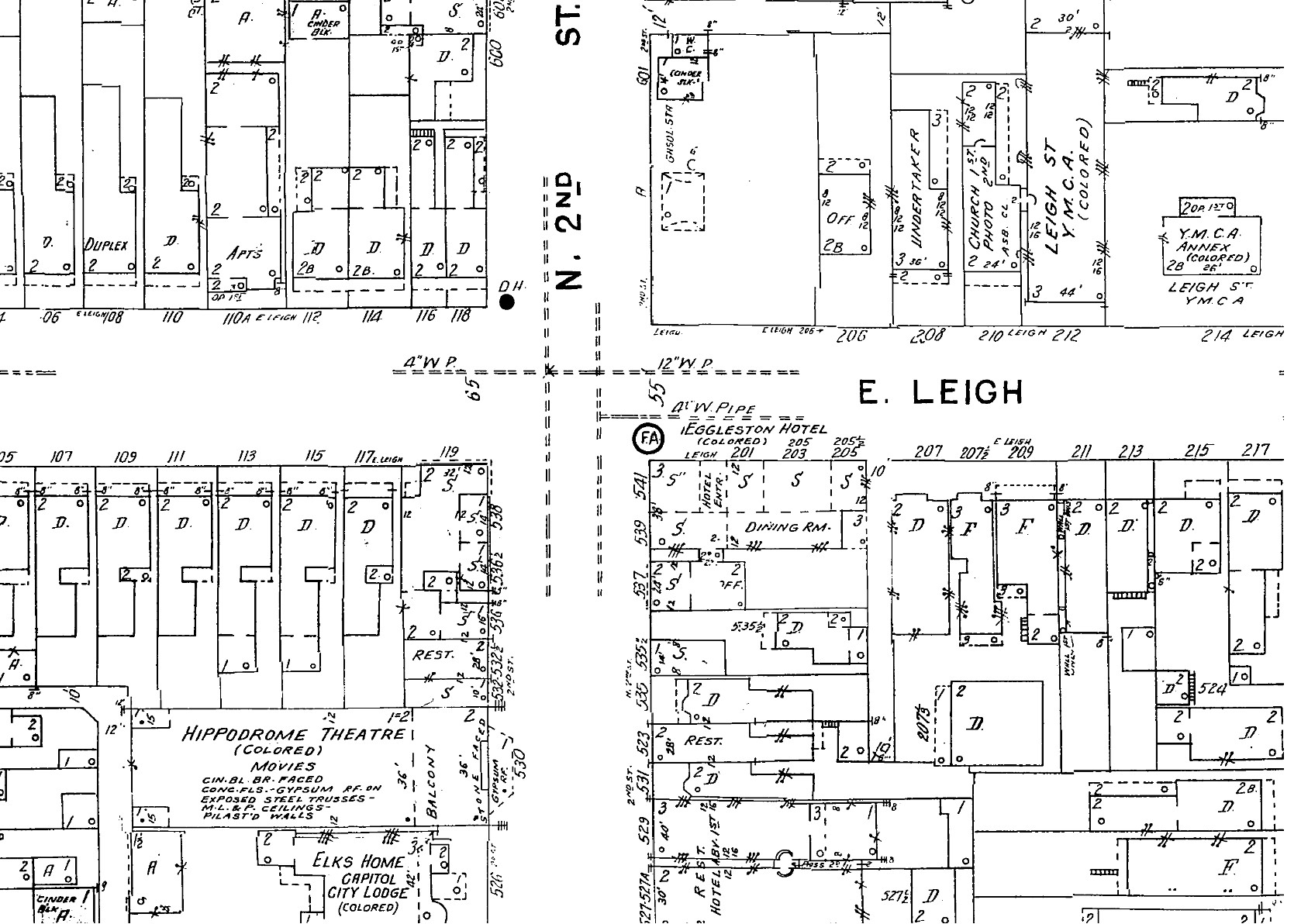

1952 Sanborn map showing Hotel Eggleston at the southeast corner of N. 2nd Street and Leigh Street. The building includes the addresses: 537-539-541 N. 2nd Street and 201-203-205 Leigh Street. The hotel entrance faces Leigh Street.

Known Name(s)

Eggleston (Miller's)

Address

2nd and Leigh St. Richmond, VA

Establishment Type(s)

Hotel

Physical Status

Demolished

Description

Per Jackson Ward National Register of Historic Places nomination, this hotel was built c. 1900 in the Italianate style (based on an article in the Richmond Planet, the building was likely completed in 1904 when it opened as Miller's Hotel). An image of the hotel appearing in a 1932 article of the New Journal and Guide shows a three-story building capped by a cornice and parapet, with a "Miller's Hotel" sign (likely the same metal as the cornice) breaking the parapet at the N. 2nd Street facade. An earlier image from 1910 indicates that a broken pediment once sat atop this sign. The facade is six bays wide with one-over-one, segmental-arched windows. Although it's difficult to tell the materials in the grainy black and white image, the facade's ground floor is either wood or metal and appears to have large windows. The length of the hotel along Leigh Street shows at least nine bays.

A later undated (c. 1990s-2000s) image shows several alterations to the facade: Permastone cladding, loss of the cornice/parapet/inset Miller's Hotel sign, and an altered storefront. It also has metal balconies on the second and third floors, connected by a metal stair. A "Hotel Eggleston" vertical sign hangs at the corner of the building at N. 2nd Street and Leigh Street. A separate "motel" blade sign hangs below and appears to be attached to the Leigh Street elevation. This description is consistent with that of the 1976 National Register listing.

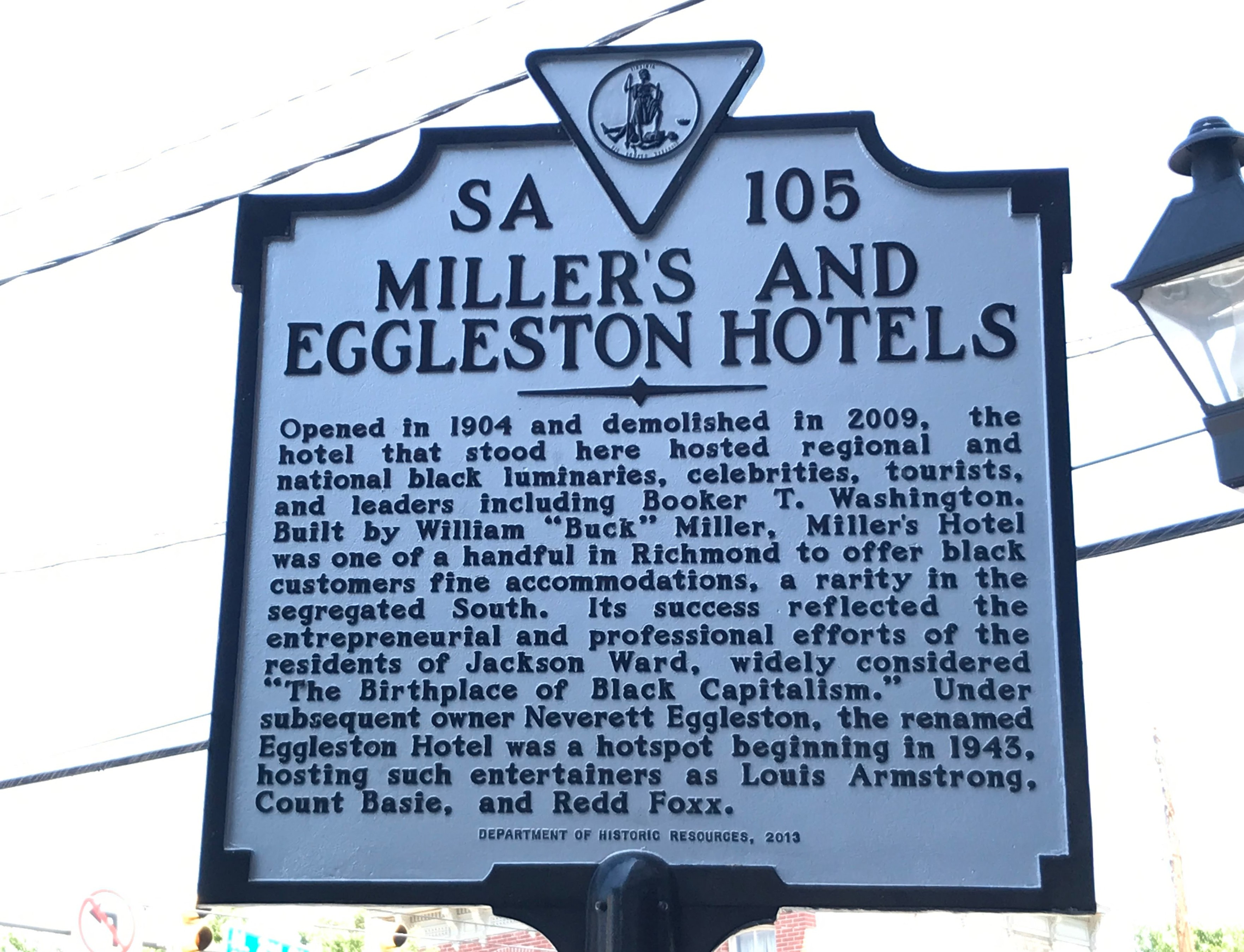

According to state marker SA105, installed on the N. 2nd Street sidewalk in 2013, the building was demolished in 2009 after a partial collapse. A new building was constructed in its place. Its metal cornice has a "Miller's Hotel" sign with projecting corbels that pays homage to the demolished building. "Eggleston Hotel" and "Eggleston Plaza" signs at the cornice also recalls the history of the site.

Detailed History

Miller’s Hotel

Miller’s Hotel was named for its proprietors, William M. “Buck” Miller and Artina Miller, a married African American couple. Buck Miller was born in Burkeville, Virginia, in either c. 1867 (source: 1880 U.S. Census) or c. 1874 (death certificate). The 1880 census notes that he was the third of eight children born to Archie and Mary Miller, the latter of whom was described as “mulatto,” and that the family was then living in Nottoway, Virginia. Artina Miller was born c. 1881 to Sam and Louisa Barnes in Mecklenburg County, Virginia.

Before opening the Richmond hotel, Buck Miller was a waiter at Murphy’s Hotel in West Virginia. When former world heavyweight boxing champion John L. Sullivan, who was dining at Murphy’s, “attempted to mistreat and abuse [Miller] about the service he was giving,” according to a later 1937 account in the New Journal and Guide, Miller “knocked out” Sullivan. The money that Miller was paid by “large newspapers … to carry his picture and story” was enough for him and his wife to eventually open Miller’s Hotel in Jackson Ward in late 1904. Its opening coincided with the emergence of N. 2nd Street (also referred to as Second Street or "The Deuce") as the neighborhood's major commercial thoroughfare and an important nationally-recognized center of Black-owned businesses; according to the National Park Service, "Second Street became known as Black Wall Street by 1903, one of the earliest references to a street being called 'Black Wall Street.'" The hotel used the address 541 N. 2nd Street and was located on the southeast corner of N. 2nd Street and Leigh Street.

Miller’s Hotel was met with praise. A December 1904 issue of the Richmond Planet notes that the “new hostelry” was “a superb place, complete in every respect and furnished without regard to cost. The taste displayed and the conveniences everywhere noticeable together with its location make it one of the most desirable places in the city.” It continues, “Strangers visiting the city will find this one of the most complete hotels among the colored people in the South. Here may be found lodging rooms, parlors, dining rooms and all other conveniences.” In 1907, the modest hotel was remodeled and expanded in anticipation of the Jamestown Tercentennial Exposition. The hotel was also equipped with a bar that moved to the N. 2nd Street side in 1914, due to liquor license requirements (the Leigh Street bar entrance was then closed).

In an era of segregation, Miller’s Hotel was one of only a handful of hotels available to African Americans in Richmond (and these appear to all have been located in Jackson Ward). Articles in the Black press indicate that the hotel was a favorite among the wealthier classes from all over the country, including honeymooners, and that it was an important social center on the eastern seaboard for people traveling north and south. A 1919 issue of the Chicago Defender notes, “Richmond is offering to the traveling public something unique and beautiful in the hotel line. The new subway dining room at Miller’s Hotel is … being used by the best people in town for parties and luncheons.” The hotel also provided a dedicated card room, which was frequented by women’s bridge clubs (one player was Hattie N.F. Walker, the daughter-in-law of Maggie L. Walker, the first African American woman to charter a bank in the United States; the Walker family lived catty-corner from the hotel, in a residence that is now Maggie J. Walker National Historic Site). Giles B. Jackson, a local pioneering Black attorney, and his mentor, prominent African American leader and educator Booker T. Washington, also used the hotel as an event space. The Billboard, in 1921, listed Miller’s as one of three hotels on N. 2nd Street that catered especially to performers of color (the others being Union Music Studio and Morris Hotel).

Buck and Artina Miller, who lived at the hotel and do not appear to have had children, were influential entrepreneurs and active community members, providing financial support to local causes. The couple ran other businesses in the area. In 1906, Buck opened a restaurant at 711 N. 2nd Street (demolished), which also catered to hotel patrons. The 1922 Richmond City Directory lists Buck as the proprietor of Miller’s Hotel Pharmacy and Artina as proprietor of Miller’s Quick Lunch, at 2204 East Main Street (building extant but altered).

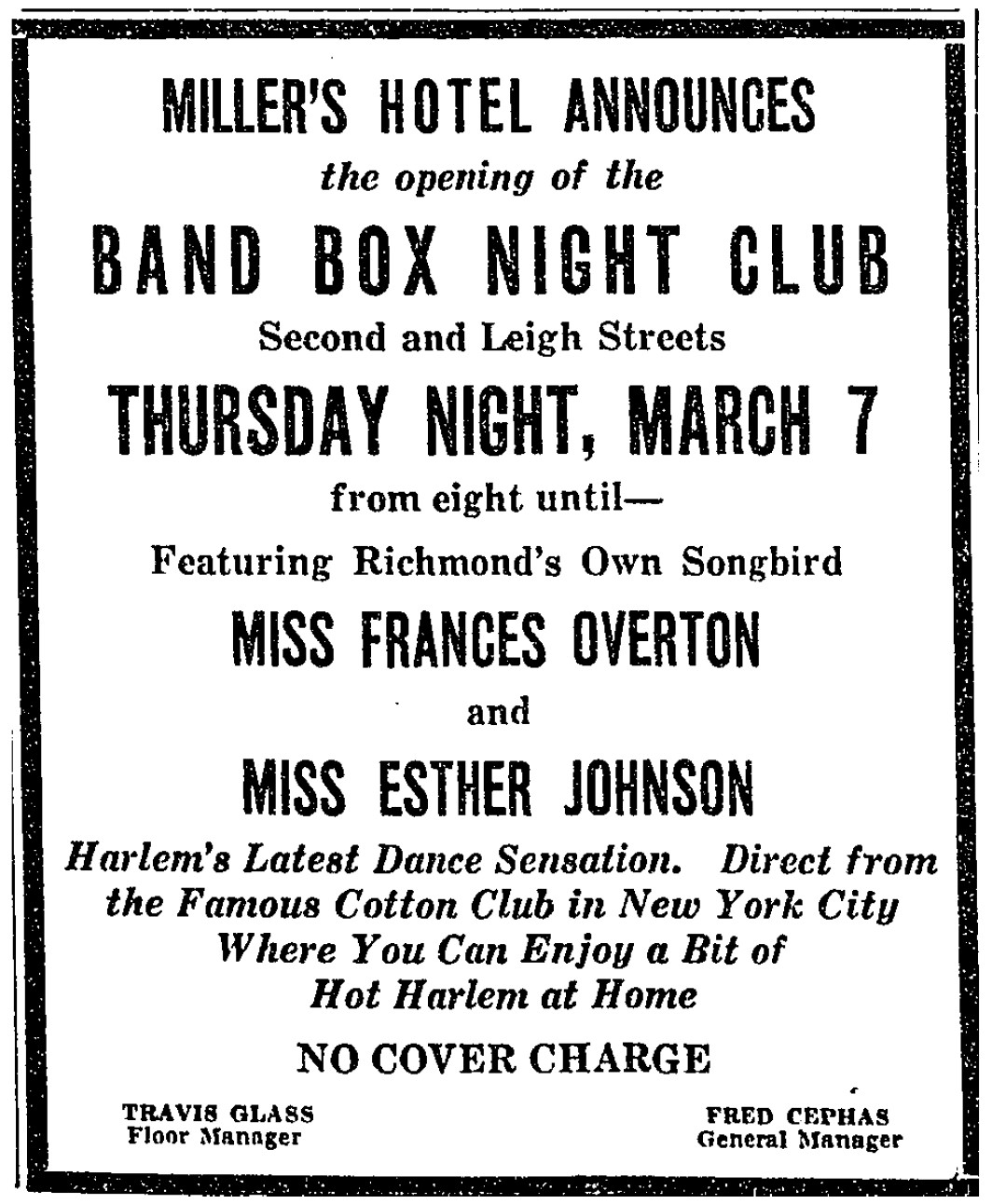

Artina Miller was integral to the hotel’s success, and it suffered following her untimely death from cancer, at about 45 years old, in 1926. New York Amsterdam News remembered her, in 1937, as “the guiding genius of the place,” a sentiment that was shared in other newspapers. Her death, along with the onset of the Great Depression, greatly impacted Buck Miller and the hotel. A few more improvements were made, however. A 1933 issue of The Panther noted that Miller’s Hotel had been completely remodeled and improved. The New Journal and Guide reported that the dining room had been combined with a nightclub to form the Band Box Night Club, which opened on Tuesday, March 7, 1935; according to an ad in the New Journal and Guide, the evening's performance featured Miss Frances Overton, of Richmond, and Miss Esther Johnson, "Harlem's Latest Dance Sensation." The ad also read "Direct from the Famous Cotton Club in New York City Where You Can Enjoy a Bit of Hot Harlem at Home." There was no cover charge. The club's general manager was Fred Cephas and the floor manager was Travis Glass (last name spelled "Glasgow" in an article in the same paper).

In early 1937, “To Let” signs appeared in the hotel windows, though Buck Miller, then retired, continued to live at the hotel until his death two years later. His extensive obituary in the New Journal and Guide as well as other remembrances of the period attest to his important status in Richmond and the fame of his hotel nationwide.

Hotel Eggleston

The National Ideal Benefits Society bought Miller’s Hotel at some point between 1937 and 1939; it was rented and managed by a man from Norfolk, Virginia. According to his own 1992 account appearing in the Richmond Free Press, Neverett A. Eggleston Sr. was working as a caterer at Lakeside Country Club in the late 1930s when Buck Miller, upset that the Norfolk man was more interested in operating the hotel’s pool hall than the hotel itself, asked Eggleston to take over its management. For about three years beginning in March 1939, Eggleston leased Miller’s Hotel, living there and running it with his wife Sallie (he continued to work at the country club while waiting to see if the hotel would be economically viable). In 1942, he bought the hotel for $25,000, renaming it Hotel Eggleston. At that time, the hotel had a grill, dining room, and pool room. The Egglestons were then living at 107 East Clay Street (extant).

Neverett A. Eggleston Sr. was born on September 14, 1898, in Henrico County, Virginia, one of nine children of Richard and Cora Eggleston. He at some point in the early 1900s lived in New York City and Newburgh, New York. In 1925, he married Sallie Juanita Robertson (1903-1974) and they had three children, Aurelia, Neverett Jr., and Jane. According to the 1950 U.S. Census, the family lived at 2112 Barton Avenue (extant). As with Buck and Artina Miller, the Egglestons were a prominent local family and active community leaders; in 1950, Eggleston Sr. was elected president of the Richmond Democratic League and, in 1963, was the co-chairman of its board of directors.

Eggleston Sr. later recalled that the World War II years kept the Hotel Eggleston, its restaurant (called Neverett’s Place in the 1950s), and other nearby businesses busy. He employed six waitresses and three cooks, and he himself was always in the kitchen. Hotel Eggleston, he said, was one of three hotels on the block where African Americans could stay in segregated Richmond, the others being Harris’s Hotel and Restaurant on the southeast corner of N. 2nd and Clay Streets and Slaughter’s Hotel, located mid-block (both also listed in the Green Book and since demolished). According to Eggleston Sr., people started calling N. 2nd Street “2 Street” during the war years. Notable people who stayed at the hotel, he said, included jazz composer Duke Ellington, baseball star Satchell Paige, singer Billie Holiday, and heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis. The guest list also included jazz musicians Louis Armstrong and Count Basie and comedian Redd Foxx. In addition to the Green Book, Hotel Eggleston advertised frequently in the Afro-American in the 1960s, boasting its air-conditioned rooms, 24-hour food service, and parking facilities. Eggleston Jr. served as the hotel’s general manager from 1955 to 1964, before opening the nearby Eggleston Motel.

Eggleston Sr. later wrote that N. 2nd Street went into decline in the mid-1970s, which he attributed to integration, as African Americans had opportunities to try other businesses in Richmond beyond those in Jackson Ward. As a result, all 30 rooms in the Hotel Eggleston were rented by the week or month. The hotel was vacant by the 1980s, though Eggleston Deli (run by Eggleston Sr.’s grandson, Neverett A. Eggleston III) and a laundromat on the Leigh Street side (owned and operated by Eggleston Sr.’s daughter, Aurelia Ford) occupied the building’s commercial storefronts by the early 1990s. Eggleston Sr. died on December 5, 1996, and is buried at Saint John Baptist Church Cemetery in Henrico County, Virginia.

Researched and written by Amanda Davis, architectural historian