In the 1860 presidential election, only one person in all of Fauquier County, Virginia, voted for President Abraham Lincoln: a wealthy slaveholder named Henry Thomas Dixon. Five years later, after serving as a paymaster in the Union army, he was gunned down in a duel with a former Confederate surgeon on the streets of Alexandria. Dixon, a former student of the University of Virginia, a Southern “gentleman,” and a Unionist, was, like many men of his time, driven by the concept of honor. Historian Joanne B. Freeman writes that “honor was at the core of a man’s identity, his sense of self, his manhood.” Importantly, “honor was also entirely other-directed, determined before the eyes of the world; it did not exist unless bestowed by others.” Disputes over honor often occurred because “a man of honor was defined by the respect he received in public” and “the impact of public disrespect… struck at [his] honor and reduced him as a man.” Particularly in the antebellum South, the concept of honor was something that elite men like Dixon used to determine status within that class. Insulting a man’s honor meant insulting his morality, social standing, character, and even his manhood. Disputes over honor were settled violently in fights or duels, with clashing swords, fisticuffs, or even pistols, as was the case with Dixon on more than one occasion.

In the early years of the University of Virginia, violence played a significant role in the school’s near failure. Many of the young men who enrolled in the first several sessions of the University in the mid-1820s settled disputes among themselves by fighting on the Lawn or near Jefferson’s “Academical Village.” As UVA history scholars Rex Bowman and Carlos Santos note, “with a [student’s] sense of honor easily bruised… the wrong word, the wrong look could easily lead to a scuffle, if not a duel.” This was due to the fact that the students were “often the spoiled, self-indulgent scions of southern plantation owners.” According to Freeman, “Southerners were quicker to duel than Northerners.” This was certainly proven true by the early students who “repeatedly used the code [of honor] … as a license for violence.” This violence went beyond just duels. Riots were common, particularly when students disagreed with the rules the University was trying to impose. Violence became almost a tradition for many students. Gambling, excessive drinking, rape, and even murder were all charges that were brought against UVA students during its first few sessions. Jefferson had hoped that honor would prevent such violence and wildness in his students, being a firm believer in the idea of student self-governance. However, at least in those early years, the wealthy sons of Southern plantation owners and their sense of honor threatened to destroy all that he had worked for.

Though a Unionist during the Civil War, Dixon would prove to be no exception to this Southern rule of honor. He was born on July 28, 1803, in Essex County, Virginia, to John Edward Henry Turner Dixon and his wife, Maria Turner. The Turner family dated back to colonial America and was a large, slave-owning family, much like the families of Dixon’s classmates at UVA. Along with his brother Turner B., Dixon attended the University in the spring and fall of 1826, UVA’s second and third sessions (their brother Edward joined Turner on grounds the following year). During that time, Henry was suspended from the University as the result of a fight with fellow student Arthur Smith. According to the faculty minutes from May 24, 1826, Smith and Dixon had been quarrelling for unspecified reasons, and their clash had turned violent. “Smith armed himself with a loaded pistol from an apprehension that he might be attacked [by Dixon].” The two met and “when Mr. Dixon aimed a blow with his fist at Mr. Smith… Mr. Smith then drew the Pistol, and, after having been hit by a stone thrown by Dixon, at him, aimed it at his antagonist and drew the trigger, without however succeeding in discharging the weapon.” Dixon was suspended until July 1 for the rest of the term, although he was allowed to return for the next session that Fall.

That November, however, the faculty voted to expel Dixon because he “absented himself from the university without permission.” Furthermore, “the faculty have good reason to believe that he has left… for the purpose of fighting a duel with Livingston Lindsay, another student, in parts beyond the limits of the State.” Further investigation resulted in Lindsay’s second stating that “he had pracitised shooting with Mr. L in consequence of learning that Mr. Dixon was a fatal shot.” The duel was apparently proposed by Dixon. Lindsay went on to have a very successful career as a lawyer, eventually becoming a judge on the Texas Supreme Court.

After his expulsion, Dixon returned to Fauquier County, where he married Annie Elizabeth Brown, on January 1, 1835. The couple had eleven children between 1836 and 1859. During this time, Dixon was a prosperous farmer in Fauquier, living at his home, Courtney, which was built in 1840. Having owned 19 slaves two decades before the start of the Civil War, by 1860 he claimed ownership of only five enslaved people. Nonetheless he remained a wealthy member of the community, reporting real estate holdings in excess of $48,000 with a personal estate of almost $6,000.

Despite his ties to the South as part of an old and influential family as well as being a slave owner himself, Dixon was the only man in Fauquier County to cast a vote for Republican presidential candidate Abraham Lincoln in 1860. He did so with “pistol in hand,” according to local historian Eugene Scheel. It is not exactly clear why Dixon broke with his slaveholding neighbors and supported the Republicans, or what his political affiliation had been in previous elections. According to historian William A. Link, he was one of only 1,887 Virginia voters to vote for Lincoln in an election that was narrowly won at the state level by the Constitutional Unionist Party’s conservative candidate, John Bell. Certainly, Fauquier was not initially a hotbed of secession sentiment for it had many supporters of Bell, who ran a close second to the pro-slavery Democrat John C. Breckinridge in the county in 1860. The county’s prominent Whig delegate to the Virginia secession convention, Robert Eden Scott, was also a firm Unionist. After the attack on Fort Sumter in mid-April 1861 and by the time of the Virginia’s ratification vote on secession, however, Fauquier, like most of the state east of the Blue Ridge, was overwhelmingly pro-secession, voting 1,809 to 4 in favor of leaving the Union. Dixon’s own family was not immune to the Confederate furor his native state. His son, Henry T. Dixon, Jr., who was only twelve-years old in 1860, was arrested and released on parole in 1863 after his own mother alerted local Federal authorities of his intention of joining the Rebel army.

During the war, the Dixon family moved to Washington, D.C., as Dixon’s Unionist views put them in danger in anti-Republican, pro-Confederate Virginia. The Richmond Enquirer reported in late April that he was serving as a lieutenant in the Kentucky Congressman Cassius M. Clay’s “Clays Guards.” The guards were an informal volunteer company based out of Washington’s famous Willard’s Hotel and formed to protect the national capital from danger in the early days of the war. Later Dixon accepted a position as paymaster for the Union army on August 7 and served with the rank of major throughout the war. While residing in Georgetown, Dixon continued to own slaves, even buying “an accomplished dining room servant” named William Johnson that December. Johnson was subsequently freed by the D. C. Emancipation Law of 1862, and Dixon filed for compensation.

Dixon also continued his pre-war feuds with his neighbors, who, he later claimed, destroyed much of his property in retaliation for his Union support. Understandably, Dixon refused to pay interest on his debts to Confederate citizens. He was also alleged to have provoked a confrontation between an old rival, Samuel Hutchinson, who had physical confrontations with both Dixon and his eldest son, Collins, before the war. Multiple sources contended that Dixon had sent a squad of Federal troops to the elderly Hutchinson’s Fauquier County home in April 1862. The soldiers then murdered Hutchinson within view of his front door. While Dixon himself seems to have avoided any affairs of honor during the war, Collins attempted to shoot a treasury clerk named George W. McGill whom he accused of slandering his sister’s honor. Though convicted of assault and battery for firing his pistol and wounding a guest in Willard’s Hotel, President Abraham Lincoln personally pardoned young Collins before he had served his entire prison sentence because “the circumstances under which the said offence was committed were such as greatly to lessen its guilt.”

Dixon and his family continued to live in Washington for the rest of the war. In early 1865, an examining board deemed him “incompetent” to continue as a paymaster in the army. The timely intervention of another Virginia Republican, Judge John C. Underwood, however, allowed Dixon to remain in his position. Underwood said it would be a great “mistake” to “[throw] a faithful officer who has suffered for his loyalty more than any one I know with a wife & ten children out of employment & support.” On July 31, 1865, Dixon mustered out of the army, as his services as a paymaster were no longer required. Dixon, now retired from the service, petitioned President Andrew Johnson for a position in the regular army on November 8, but his petition was never addressed as he was mortally wounded in a duel two days later.

Dixon was shot by a Dr. Thomas Clay Maddux in Alexandria on November 10. Maddux was also a resident of Fauquier County and, like Dixon, came from a traditional Southern planter-class family. According to his obituary, Maddux was “the seventh son and twelfth child of Thomas L. Maddux, a wealthy farmer and a native of [Fauquier County], who was a lineal descendant of Sir William Maddux, of Seven Oak Manor, England.” Unlike, Dixon, however, Maddux had served as a surgeon in the Confederate army and was a staunch secessionist, being present at the firing on Fort Sumter according to his service record. The remainder of his post-war record is poorly documented, however, with various sources saying he was with the 1st South Carolina Regiment at several engagements as part of General Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia or that he served as a surgeon at the military hospital in Barnesville, Georgia, prior to being captured while trying to join General Joseph E. Johnston’s forces near Bentonville, North Carolina, at the war’s end. Despite Maddux’s service in the Confederate army and Dixon’s work as a paymaster for the Union, their contemporaries acknowledged that their fight was not a blue vs. gray altercation sparked by their political differences, but rather a “personal encounter.”

According to the Alexandria Gazette, hostilities between Dixon and Maddux had begun in 1857, when one of Dixon’s sons, Collins, “got into some trouble.” “The sheriff… had a warrant for the arrest of young Dixon… and Dr. T. Clay Maddux volunteered to make the arrest,” something that “the elder Dixon,” being “of a warlike nature… would doubtless resist.” The Gazette continues, relating that “when Major Dixon saw [Maddux] on his premises and became aware of his errand, he brought out a gun and discharged its contents into the breast and shoulders of Dr. Maddux.” Maddux “received a bullet through his neck and lungs, which occasioned a paralysis from which he did not recover for many months,” but ultimately survived the encounter. An 1857 report on the trial showed that Dixon received a sentence of a $500 fine and a 24-hour stay in a local jail.

The two did not meet again until after the war on the evening of October 27,1865, when Maddux walked up to Dixon at the Mansion House in Alexandria, where Dixon was sitting in an armchair by the fire, and spat in his face before Dixon had even recognized his old rival. According to the general consensus of accounts, Maddux was gone before Dixon could retaliate, but “it was then seen that the next time the two men met one or the other would be killed, or probably both.” Maddux was subsequently arrested for the assault by a local military court though Dixon told a newspaper “he had nothing whatever to do with having the Dr. arrested, and that he did not wish him arrested.” Still, Dixon’s honor had been insulted and, given his violent past, it was likely he would try to avenge it.

On the morning of November 10, Dixon and Maddux had their final encounter in the street outside of Alexandria’s City Hotel. Despite the fact that Dixon claimed he “did not intend to use deadly weapons unless [Maddux] first indicated a purpose to do so,” a gunfight broke out that left Dixon fatally wounded and Maddux grazed by a shot. According to the Evening Star, “Major Dixon [received] two balls from a navy revolver in the right side, just above the hip joint, both fatal.” Dixon reportedly fell and said “I’m killed” when he was asked if he was shot. He then “lingered in great agony through the night.” The single shot he fired in return “passed through the leg of [Maddux’s] pantaloons.” Witness accounts disagree on who fired the first shot. Dixon said in a statement to his lawyer that he had passed Maddux and that Maddux then shot him the first time, leading Dixon to turn around and shoot back, when he was shot by Maddux for the second time, thereby causing him to miss and only catch Maddux’s pant leg. In an alternate account, a friend of Maddux’s states that Dixon looked as though he was going to pull a gun when the friend alerted Maddux to his foe’s presence. Maddux then turned as Dixon shot, causing him to miss, and shot Dixon twice in self-defense. Dixon lingered through the night dying on the morning of November 11 despite having received “the best surgical assistance” available.

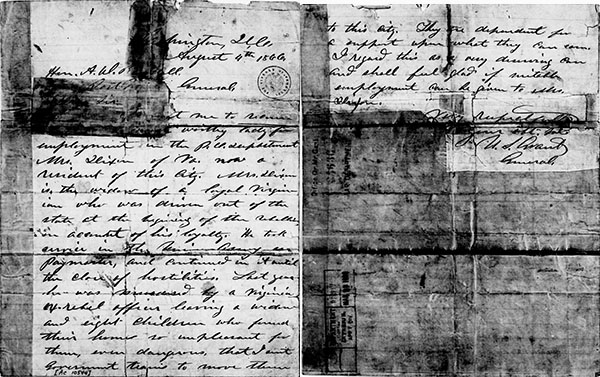

Maddux was ultimately acquitted a few days later in a local court by Justice of the Peace S. M. Beach who determined that Maddux “was justified in shooting Major Dixon.” Arrested a short while later on murder charges and called to appear before the county court, Maddux was “discharged without further examination” on December 4. Maddux himself was shot and killed in an election dispute on November 8, 1881, outside of Baltimore, Maryland. Dixon’s family returned to Fauquier County briefly, but ultimately moved to Washington by the arrangement of General Ulysses S. Grant, who knew that their former home had become “unpleasant for them, even dangerous” due to Dixon’s political leanings and that Dixon had been “a loyal Virginian who was driven out of the state at the beginning of the rebellion, on account of his loyalty.” Grant even interceded with Postmaster General Alexander W. Randall, obtaining a post office position for Annie after her husband’s death. A special act of Congress granting Annie Dixon a pension of $25 a month commenced on July 11, 1890, allowing her the amount for active duty soldiers rather than retired ones. According to the bill, this was because “Major Dixon was murdered at the city of Alexandria by a Rebel surgeon, his loyalty having made him very obnoxious to the disloyal,” though no other record suggests the quarrel was born out of their political differences. Annie continued to receive a pension and live in Washington until her death on February 13, 1899. Both Dixon and his wife are interred at Arlington National Cemetery, making Dixon one of five UVA Unionists to be buried there.

From his youthful days at UVA to the final painful hours of his life, Dixon was driven by that elusive concept that is nearly impossible to grasp in the twenty-first century: honor. Dixon, imbued with a sense of his gentlemen’s honor by the Southern culture he lived in, not to mention the university he attended, lost his life trying to defend that notion. Despite his convictions as a Unionist, Dixon still seems to have held at least this prominent piece of Southern culture in high regard. Bertram Wyatt-Brown argued that “few Yankees would feel compelled to settle ideological differences on a dueling field,” and scholars Bowman and Santos similarly demonstrated in their study of antebellum UVA that: “Southerners were different. The willingness to fight and die found its purest form in the duel.” Dixon, speaking through his actions, stood as a Southerner when it came to the concept of honor, and, in many regards, was just as committed to it as he was to the cause of the Union, being equally willing to give his life for either. His story is very telling of the dual nature of the Southern Unionist and, ultimately, exemplifies the concept of honor in the nineteenth century and the lengths men would go to defend it.

Images: (1) Henry T. Dixon (courtesy Ancestry.com User Profile); (2) "Courtney" or "Buena Vista," Henry T. Dixon's home in Fauquier County (courtesy Stephanie Williams at the Virginia Department of Historic Resources); (3) U. S. Grant to A. W. Randall, August 4, 1866 (courtesy Library of Congress); (4) Henry T. Dixon's grave (courtesy Arlington National Cemetery).

Compiled Service Records for Henry T. Dixon, RG 94, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Washington, D.C.; Pension Records for Henry T. Dixon, RG15, NARA; Henry T. Dixon to the Office of the Adjutant General, August 7, 1861; John C. Underwood to “Mr. President or Mr. Secretary Stanton,” March 22, 1865; and Commission Branch File for Henry T. Dixon, RG94, NARA; Petition of Henry T. Dixon, Records of the Board of Commissioners for the Emancipation of Slaves in the District of Columbia, 1862-63, RG 217, NARA; accessed through Fold3.com; “Pardon of Collins Dixon,” May 3, 1864, RG 59, Entry 897: Appointment Records, General Pardon Records, Pardons and Remissions, NACP, NARA; “Pardon File of Collins Dixon,” May 3, 1864, RG 204, Entry 1a: Pardon Case Files, 1853-1946, NACP, NARA. United States Federal Census and Slave Schedules, 1840, 1850, 1860, 1870, 1880, accessed through Ancestry.com; “Session 2 of the Faculty Minutes January 8, 1826 - December 22, 1826,” accessed through Jefferson’s University — the Early Life (http://juel.iath.virginia.edu/node/343?doc=/juel_display/faculty-minutes/Sessions/session-002); Alexandria Gazette, October 28, 30, November 1, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 23, December 4, 1865; U. S. Grant to A. W. Randall, August 4, 1866, in The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant Digital Edition (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, Rotunda, 2018, http://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/GRNT-01-16-02-0153 (accessed 15 Jul 2019)); “Trial of Henry Dixon, Esq.” Richmond Enquirer, September 15, 1857; Richmond Enquirer, April 23, 1861; Alexandria Gazette, June 4, 1863; Evening Star “Local News,” The Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), October 5, 1863, May 6, 1864, November 11, 1865; “The Shooting of Major Henry F. Dixon,” The Daily Standard (Raleigh, North Carolina), November 20, 1865; “Dixon, of Yazoo,” The Richmond Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia), August 22, 1879; “Killed at the Polls,” The Baltimore Sun, November 9, 1881; “Mortuary. Judge Livingston Lindsay,” The Galveston Daily News (Galveston, Texas), January 31, 1892; “A Tragedy Recalled,” The Alexandria Gazette (Alexandria, Virginia), July 20, 1895; Bowman, Rex, & Santos, Carlos, Rot, Riot, and Rebellion: Mr. Jefferson’s Struggle to Save the University That Changed America, (Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia Press, 2013); Clemens, William Montgomery, “The Turner Family Magazine: Genealogical, Historical, and Biographical,” Vol. I & II, January 1916 to April 1917, (New York: William M. Clemens, 1920), accessed through Archive.org (https://archive.org/stream/turnerfamilymaga00newy/turnerfamilymaga00newy_djvu.txt); Current, Richard Nelson, Lincoln’s Loyalists: Union Soldiers from the Confederacy, (Boston, Massachusetts: Northeastern University Press, 1992); Brown, Kathi Ann, Walter Nicklin, John T Toler and Fauquier Historical Society (Va.), 250 Years in Fauquier County: A Virginia Story (Fairfax, Va: GMU Press, 2008); Caldwell, Susan Emeline Jeffords, Lycurgus Washington Caldwell, J. Michael Welton, John K. Gott, and John E. Divine, "My heart is so rebellious": the Caldwell letters, 1861-1865 (Warrenton, Va: Fauquier National Bank, 1991); Freeman, Joanne B., Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic, (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2012); Keller, Roger, Roster of Civil War Soldiers from Washington County, Maryland, Second Ed., (Baltimore, Maryland: Clearfield, Genealogical Publishing Co., 2008); Link, William A. Roots of Secession: Slavery and Politics in Antebellum Virginia (Chapel Hill, London: University of North Carolina Press, 2003); Scheel, Eugene M., The Civil War in Fauquier County, Virginia (Warrenton, Va: Fauquier National Bank, 1985); Toner, Joseph Meredith, Transactions of the American Medical Association, Vol. XXXIII, (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Times Printing House, 1882); Williams, Kimberly Protho, A Pride of Place: Rural Residences of Fauquier County, Virginia, (Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia Press, 2003); Wyatt-Brown, Bertram, Honor and Violence in the Old South, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986); “Harry Dixon,” Early Colonial Settlers of Southern Maryland and Virginia’s Northern Neck Counties, https://www.colonial-settlers-md-va.us/getperson.php?personID=I026486&tree=Tree1; “Henry Thomas Dixon,” Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/119557693/person/352005164300/facts?_phsrc=iJD10&_phstart=successSource); “Terry Mason’s Family History Site,” http://www.tmason1.com/pafg2100.htm; “Major Henry T. Dixon,” FindAGrave.com (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/34883545/henry-t.-dixon); “Annie Elizabeth Brown Dixon,” FindAGrave.com (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/73241749/annie-elizabeth-dixon); “Dr. Thomas Clay Maddux,” FindAGrave.com (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/11221073); “Virginia County Vote on the Secession Ordinance, May 23, 1861,” New River Notes, https://www.newrivernotes.com/historical_antebellum_1861_virginia_voteforsecession.htm.