After the Civil War, the University of Virginia made significant efforts to commemorate its Confederate past. For example, in 1893, it erected a bronze statue in honor of all Confederate soldiers who had died in Charlottesville hospitals, bearing the inscription, “Fate denied them victory but granted them glorious immortality.” In addition, plaques honoring UVA Confederate alumni killed in the war were erected on the Rotunda in 1906, and six years later the University held a special reunion for surviving veterans. However, only Confederate veterans were invited and indeed no such honors or special recognition have ever been bestowed on the sixty-nine Cavaliers who fought for or supported the Union, their stories neglected by a University that actively embraced the Lost Cause version of Civil War history. Despite the fact that this group of Union Veterans was overwhelmingly made up of prominent citizens in their communities, these Union men who were granted victory were denied the “glorious immortality” bestowed upon their southern counterparts, both on and off UVA’s grounds.[1]

In his book, Sing Not War, historian James Marten discusses the veterans “who fit less easily back into their prewar lives, who suffered from disabilities and poverty, from mental handicaps and institutionalization.” Despite suffering from some of the same health conditions and sharing a commitment to preserve the memory of their service for future generations, UVA’s veterans were very different from the type of soldier that Marten describes. In every way, they were the elites of their time. They were professional men who held positions of prominence in their local communities in proportionally higher numbers than their fellow Unionists, and, probably, their fellow alumni in gray. [2]

Analyzing UVA veterans’ post-war experiences requires examining where they lived and the elite, professional occupations they held after 1865. It also requires spending some time focusing on their post-war health issues, best seen in their pursuit of pensions and other forms of government support such as taking up residence at Soldiers Homes established across the country after the war. Finally, a number of UVA’s Unionists showed an earnest desire to shape the way that subsequent generations remembered the war by joining and supporting veterans’ organizations such as the Grand Army of the Republic and the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States.

Most UVA Unionists attended in the antebellum period or during the secession crisis of 1860-1861. Chemistry professor Robert E. Rogers, music instructor James M. Deems, modern languages instructor Samuel E. W. Becker, and drawing instructor Henry V. Morris, taught at the University before the war. Five Unionist students attended after the war ended in 1865. Professor Albert H. Tuttle, also arrived on grounds after the war, serving as the Miller Chair of Biology and Agriculture from 1888 to 1913.[3] For the men who were at UVA before the war, they would have encountered a strong pro-slavery attitude at the University for it catered to the sons of elite Virginia and southern families. Indeed, the vast majority of students who attended the University before the war joined the Confederacy, and hundreds of Confederate veterans enrolled during or after the conflict. James O. Broadhead, writing to approve of his brother’s decision to leave UVA early in 1858, wrote critically of southern bias at UVA, noting that the South as a whole was “perfectly mad” on the subject of slavery, observing that “there is no telling to what excess of folly, the Southern people will permit themselves to be led.” The handful of Union veterans on grounds in the late 1860s and early 1870s would have similarly been outnumbered by their former adversaries and subjected to the narrative of the Lost Cause, an ideal that historian Elizabeth Varon has shown increasingly gained strength at the University in the form of statues and other public memorials erected later in the century.[4]

Although most men lived long lives after the war was over,[5] three UVA Unionist alumni did not live to see the end of 1865. James Melville Gillis, a career naval officer who had helped to found the Naval Observatory, died on February 9, 1865, at the age of fifty-three due to complications of a stroke. Less than two weeks later, Alexander G. Pendleton, a professor at the observatory during the conflict, took ill on his way home from work one evening and died that same day, on February 16. Henry Thomas Dixon, a paymaster during the war, was shot in Alexandria, Virginia, on November 10, 1865, by Thomas Clay Maddux, a man who was an old antebellum rival from a previous duel. Dixon succumbed to his wounds early the next morning.[6]

For those who went on to live long lives, 69 percent (forty-seven veterans) of UVA’s Unionists returned to and lived at least briefly in the same state that they had lived in before the war. Historian Russell L. Johnson’s study of postwar Dubuque, Iowa, found a similar pattern in that more than 50 percent of the soldiers who had fought for the Union and survived returned to Dubuque after the war, compared to only a forty-two percent civilian persistence rate. Only a fraction of UVA Unionists (twelve) lived in the former Confederacy after the war, two-thirds of whom lived in Virginia (8). Many of the veterans took residences in eastern or Midwestern locales that supported the Union cause, including Pennsylvania (nine), New York (six), Washington, D.C. (five), Kentucky (five), Ohio (six), and Maryland (five). A number either moved to or returned to their homes in western states, the most common place being in Missouri, with fourteen of the veterans living there at some point after the conflict ended. Aside from those who spent time in Missouri, UVA’s Union veterans lived in nineteen different locations in other western states, including Utah, Colorado, Iowa, Washington, Arizona, Kansas, Nevada, Nebraska, Wyoming, and California. This movement follows what seems to have been a national trend that historian Dixon Wecter describes as “a major [tide of migration] toward the West.” Men who moved West included John A. Hunter, Jacob Boreman, Walter Scott Ditto, and Albert H. Tuttle (who retired to California after teaching at UVA for many years).[7]

Historian Russell L. Johnson also states that “geographic and social mobility were inversely related; the less social mobility individuals achieved, the more geographically mobile they were likely to be.” This was certainly true of some of UVA’s more mobile veterans such as James Edgar Montandon, who moved from Chicago, Illinois; to Topeka, Kansas; to Benson, Arizona; to Tacoma, Washington; working as a farmer, bookkeeper, painter, and for a railroad company. The most prominent Unionists, such as Missouri lawyer James O. Broadhead, Arkansas politician William M. Fishback, or New York theologian Charles A. Briggs, however, returned to their pre-war homes and stayed put there afterward, following Johnson’s described trend.[8]

In Sing Not War, historian James Marten writes that only 7 percent of Union veterans “owned their own businesses or worked as attorneys or medical professionals.” The vast majority worked in a variety of skilled or unskilled trades as they had before the conflict erupted in 1861. By contrast, the majority of UVA’s veterans were doctors, lawyers, or ran either their own or a family business or estate, with many of them holding a variety of positions at different points in their careers. After all, these men had trained at UVA or subsequently at other colleges for professional careers. Of the many occupations held by these veterans, twenty-one were lawyers, such as Charles Ewing; twent-five were doctors, including William S. Forbes; nineteen worked in civil service including James O. Broadhead; twelve were career military, like General Wray Wirt Davis; and fourteen were politicians like the Republicans Robert H. Shannon, U.S. Commissioner for the Eastern District of Louisiana, and John Phillips Turner, who served multiple terms as the mayor of Milford, Ohio. Three men, Briggs, Tuttle, and Forbes, held distinguished University faculty positions. Occupations held by the remaining men included such careers as businessman, farmer, engineer, instructor, bookkeeper, clerk, painter, and broker. A number of men, such as John A. Hunter of Lancaster, Ohio, a childhood friend and classmate of Ewing, worked in a variety of careers after the war, in his case as a lawyer, a judge, and a civil servant. [9]

For veterans who were disabled in some way in the line of duty, pensions often served as an extra means of earning money for a family or, in some more extreme cases, replaced a soldier’s career. Congress passed three main laws impacting Civil War pensions: the General Law (1861), the Arrears Act (1879), and the Act of 1890. Each of these acts made pensions more liberal in terms of the amount of money as well as lowering the qualifications for receiving a pension. Despite veterans’ and their families’ real need for public aid, there was a social stigma surrounding pensions for veterans born largely out of Gilded Age America’s belief in what Marten refers to as the “capitalist ethos,” symbolized by successful men like John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie, which celebrated these industrial “prophets of progress” as part of a post-war “cult of the self-made man and the philosophy of laissez-faire.” Veterans who had chronic illnesses or physical and mental disabilities as a result of their service were often looked down upon as lesser citizens because they were not able to subscribe to this ethos in the same way, an issue that many contemporaries blamed on veterans’ alleged immorality.[10]

Perhaps this is the reason that, of UVA’s sixty-nine Union veterans, only twenty-four applied for a pension. Of those twenty-four, only nineteen pensions were granted (79.16 percent) a low success rate when compared to the 92.6 percent of White Union veteran applications that succeeded as documented by historian Donald Shaffer.[11] Veteran Frank Doan, who had been discharged from the navy due to poor health in August 1863, received a pension of eight dollars per month in 1906 due to dyspepsia and general debility. As his health steadily deteriorated, the pension was increased to twenty-one dollars per month prior to his death in 1928. Likewise, Doctor Marion Goss, a veteran of the 149th Indiana, received a pension to aid him in his declining years. His superior officer testified that Goss had spent much of his time in the service suffering from rheumatism, diarrhea, malaria, and eye trouble. His pension was further supported by his personal doctor, William H. Gillum, a fellow UVA alumnus who had surrendered with General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox. Both Goss and Doan, able to show that their post-war ailments had links to their Civil War service, were symbolic of their fellow UVA Unionists who relied on pensions to support themselves and their families in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[12]

Despite the obvious need of thousands of Union veterans who became part of the increasingly expensive pension system, the social stigma surrounding pensioners may have influenced some of the more famous names among UVA’s Unionists such as William Meade Fishback, Robert H. Shannon, James O. Broadhead, and Charles Briggs, not to apply at all. Despite being a pensioner and proud Union veteran himself, Bernard G. Farrar, was not shy about criticizing the pension system in an 1887 interview with The New York Times. “I think our pension system is a fraud. I raised three regiments, in whole or in part, and I am annoyed to death with able-bodied men coming to me to help get them pensions,” he complained. “Unless the man is decrepit I invariably refuse.” Farrar’s statement captures both a wider social stigma surrounding pensions in the North as well as general frustration veterans felt toward the pension system, even from those who were receiving aid.[13]

UVA Unionists’ widows had higher success rates with applying for pensions, however; of the twenty who applied, eighteen were granted (90 percent success rate). This is well above the 83.7 percent success rate of White Union veterans’ widows in Shaffer’s study. Of those who were unsuccessful, Richard G. Woodson’s wife, Grace, was denied a pension due to her husband’s dishonorable discharge. Others who did succeed, such as Frances Febiger, widow of Colonel George L. Febiger, were granted pensions because they were successful in showing their husbands died from medical conditions contracted in the service. Like many veterans, widows saw their pensions increase through the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and heavily relied upon them for their support after their husbands’ deaths. In one case, Virginia Ewing, the widow of General Charles Ewing, saw her pension rise from twenty to fifty dollars a month in the 1890s due to a special act of Congress passed on her behalf.[14]

For veterans who could not survive solely off of pensions or required more intensive care, the Federal government founded the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. The goal for these soldiers’ homes was to provide for the veterans who were incapable of taking care of themselves, or had no family to do so. Nearly 100,000 soldiers were eventually admitted to either state or Federal homes, but prejudices against men who resided in them were even worse than for those who received pensions. James Marten notes that “Americans still assumed ‘that poverty was a consequence (or, alternatively, a cause) of poor morals and poor habits.’” In the eyes of the general public, “Americans who submitted to confinement in homes… had, simply by allowing themselves to become dependent, made themselves less than complete citizens.”[15]

Two of UVA’s veterans spent the last few years of their lives in soldiers’ homes. Magnus Stribling suffered from a range of illnesses and conditions brought on by the war as well as habitual drunkenness, and, as a result, his daughter Fannie M. Moore became his legal guardian on May 22, 1899. On June 10, he moved into the Central Branch of the National Homes in Dayton, Ohio, where he lived until he died on April 24, 1902. Robert W. Starke, another inmate of the national homes, was a career military man, serving stints in both the navy and army from 1857 until 1870. Following his final discharge from the army, his health worsened steadily until he was admitted to the City Hospital in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1880. At the time of his admission, he had been unable to work for the previous ten months. Finally, he was admitted to the national soldiers home in Hampton, Virginia, on August 24, 1889, and lived there until he died on February 1, 1896. Without question, both Stribling and Starke desperately needed the home and medical care provided by the national home system, even if neither had wanted or planned on living and eventually dying in a state totally dependent on the Federal government for their support.[16]

Various veterans’ groups formed in the aftermath of the war were instrumental in creating these veterans’ homes as well as helping to make pensions more liberal. One such group was the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR). The GAR was the first veteran’s group to organize nationwide; it started in 1866 in Decatur, Illinois, when a small group of Union veterans founded the first post. In the 1880s and 1890s, it saw an unprecedented and rapid growth rate. Any soldier or sailor who had received an honorable discharge was eligible for membership, and each post was organized by state, which then set the policy for the local posts that fell under its authority. In their promotion of pensions and soldiers’ homes, the GAR offered a view of these men that countered the social perception of the lazy, dirty, untrustworthy old veteran; rather, the GAR depicted them as heroes, men who sacrificed the good years of their lives, as well as their health in many cases, for the sake of their nation.[17]

Aside from promoting veterans’ issues in politics, the GAR also provided aid to veterans in need and organized annual encampments in which all of the members of the GAR nationwide and their families would come together to commemorate their experience serving in the war. According to historian Barbara Gannon, the GAR helped to shape the “Memory (with a capital M)” of the war. Gannon describes Memory not as “an individual’s personal memory, but a group’s, a generation’s, or a nation’s collective understanding of, or agreement on, a shared interpretation of its past.” Union veterans in the GAR, Gannon wrote, promoted the “Won Cause,” a narrative of the Civil War history that celebrated the Union victory and its moral superiority to the Confederates’ “Lost Cause” version of events. Unionists, she continues, “embrac[ed] emancipation—Liberty—if for no other reason that the end of slavery guaranteed the survival of the nation—Union.” UVA’s Unionist veterans, in joining groups like the GAR, eagerly embraced the Won Cause at a time when most of their fellow alumni and the leadership of their alma mater embraced a pro-Confederate narrative of the war’s history. So far, six UVA veterans have been identified as GAR members: Bernard Gaines Farrar, Joseph Cabell Breckinridge, James M. Deems, Henry V. Morris, Jacob Mater, and Marion Goss.[18]

Another important veterans’ group was the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS). MOLLUS was founded April 1865 in Philadelphia and modeled off of the Society of the Cincinnati, a Revolutionary War veterans’ group for both French and American soldiers. Only Civil War officers and their eldest male descendants were eligible for membership in MOLLUS. Although the organization spread slowly at first, like the GAR it saw a significant upturn in activity and membership in the 1880s, increasing from only having members in six states by the end of the 1860s to spreading across fourteen states by 1891. Though not as large due to its exclusivity, MOLLUS, like the GAR, offered veteran officers an opportunity to “[strengthen] the ties of fraternal fellowship and sympathy formed by companionship-in-arms,” as well as “[advance] the best interest of the soldiers and sailors of the United States… extending all possible relief to the widows and children of” members. MOLLUS was also invested in “cherishing the memory and associations of the war,” doing things like organizing ceremonies to honor the memory of President Abraham Lincoln, giving literary awards to encourage Civil War writing, supporting the Civil War Library and the Museum of the Loyal Legion, and “erect[ing], restor[ing], and maintain[ing] plaques and monuments commemorating events and personalities of the Civil War.”[19]

Bernard Gaines Farrar, the most active of UVA veterans in MOLLUS based on extant records, served as the Senior Vice Commander of the Missouri Commandery of MOLLUS from 1909 to 1910 and as the Commander from 1910 to 1911. Joseph Cabell Breckinridge was another active member, serving as junior vice-commander for a time. Eleven other UVA Unionists belonged to MOLLUS, including Charles Eversfield, James M. Deems, Charles Irving Wilson, Gabriel Lewis Buckner, George Lea Febiger, James O. Broadhead, Wray Wirt Davis, William Smith Forbes, William E. Hopkins, John Edward Summers, and George Worth Woods.[20]

As indicated by their prominent, successful careers and membership in elite veteran organizations like MOLLUS, UVA’s Unionists were by and large members of the elite or middle classes of American society compared to their fellow Union veterans. These men were recognized as leaders of their communities and states, with a number gaining national prominence during their careers. Despite dealing with many of the same issues surrounding pensions, soldiers’ homes, and shaping the public’s recollection of their wartime service, these men stood out as atypically elite compared to the average Union veteran and their fellow UVA alumni in gray. A year after UVA held a special celebration in 1912 for its Confederate students, a Virginia newspaper chastised the school for its neglect of Unionist alumni. Meekly admitting “that no complete list has been made of the University alumni who saw service in the Union army,” the University of Virginia Alumni News lamented the oversight but declined further investigation. Despite their lack of memorialization or recognition on grounds one hundred years ago or today, UVA’s Unionists were unquestionably some of the University’s most important and influential Civil War veterans in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[21]

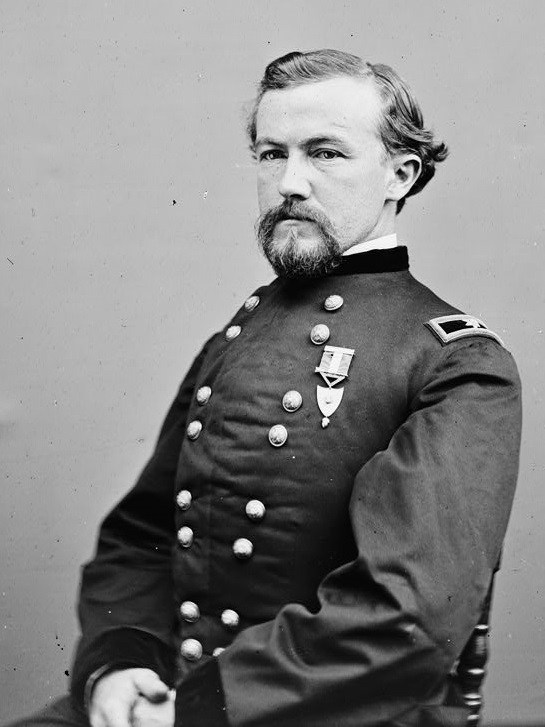

Image: General Charles Ewing (courtesy Library of Congress).

[1] This essay focuses on the sixty-five UVA alumni, faculty, or students, who served in the Union military during the war. Please see the biographies of Henry W. Davis, Charles B. Calvert, and John W. Menzies, three men who served in the House of Representatives during the conflict. Ervin L. Jordan, Jr, Charlottesville and the University of Virginia in the Civil War, 2nd ed. (Lynchburg, VA: H.E. Howard Inc., 1988), 102-104; Karin Kapsidelis, “Turning Point,” VIRGINIA Magazine, Winter 2017 (https://uvamagazine.org/articles/turning_point).

[2] James Marten, Sing Not War: The Lives of Union & Confederate Veterans in Gilded Age America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 3.

[3] University of Virginia Student Catalogues 1825-1888, accessed through JUEL (http://juel.iath.virginia.edu/resources#_ftn6); For more on Professor Tuttle, see Clayton J. Butler, “Albert H. Tuttle: UVA’s Unionist Professor,” http://community.village.virginia.edu/unionist/node/519.

[4] James O. Broadhead to William F. Broadhead, February 7, 1858, James Broadhead Papers, Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis, Mo. (transcribed here); Elizabeth Varon, “The Original False Equivalency” in Charlottesville 2017: The Legacy of Race and Inequity, ed. Louis P. Nelson & Claudrena N. Harold (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2018), 46-47.

[5] The last of UVA’s Unionists, Frank Macnamara Doan, died on April 25, 1928 (Pension Record for Frank M. Doan, RG15, NARA).

[6] James Melville Gilliss in Appleton’s Cyclopedia of American Biography, 1600-1889, Vol. II., accessed through Ancestry.com; “Local News,” Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), November 11, 1865; Letter from Commander William B. Whiting, February 17, 1865, accessed June 21, 2019 (http://hopewell.org/Genealogy/genealogy%20database%20manning%20hodges%20and%20allied%20families/i256.htm); Henry Winter Davis, a Radical Republican from Maryland who did not fight or raise a regiment during the war, died on December 30, 1865 in Baltimore of pneumonia (“Davis, Henry Winter (1817-1865),” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress (http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=D000104).

[7] Post-war residence locations for each Unionist were identified in the United States Federal Census Records, 1870-1920, accessed through Ancestry.com; Russell L. Johnson, Warriors Into Workers (New York: Fordham University Press, 2003), 292; Dixon Wecter, “The Veteran Wins Through,” in The Civil War Veteran: A Historical Reader, ed. Larry M. Logue & Michael Barton (New York: New York University Press, 2007), 91.

[8] Johnson, Warriors Into Workers, 294; United States Federal Census, 1870, 1880, 1900, accessed through Ancestry.com; William E. Parrish, “Broadhead, James Overton,” American National Biography, published February 2000 (https://doi.org/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.0400149).

[9] Marten, Sing Not War, 5; “UVA Unionists” Database, Nau Civil War Center; Jim Smith, "John Phillips Turner, UVA student," email, December 5, 2020.

[10] Marten, Sing Not War, 1-32. For a short synopsis of Civil War pensions, see Kathleen L. Gorman, “Civil War Pensions,” Essential Civil War Curriculum, https://www.essentialcivilwarcurriculum.com/civil-war-pensions.html.

[11] Donald R. Shaffer, After the Glory: The Struggles of Black Civil War Veterans (Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2004), 209; Pension Records, RG15, NARA.

[12] Pension Records for Frank Doan and Marion Goss, RG15, NARA. For more on Goss, see Amelia Wald, “Hoos in the Hoosier State: The 149th Indiana, UVA’s School of Medicine, and Post-War Reconciliation (Parts 1 & 2),” UVA Unionists (http://community.village.virginia.edu/unionist/node/521 and http://community.village.virginia.edu/unionist/node/520).

[13] “More of Tuttle’s Record,” The New York Times, July 24, 1887; Marten, Sing Not War, 204.

[14] Shaffer, After the Glory, 209; Pension Records for Samuel Few, Richard Goodridge Woodson, George Lea Febiger, and Charles Ewing, RG15, NARA.

[15] Marten, Sing Not War, 159-198.

[16] Pension Records for Magnus Stribling and Robert Starke, RG15, NARA.

[17] Marten, Sing Not War, 159-198; Larry M. Logue, To Appomattox and Beyond (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1996), 94-101.

[18] Logue, To Appomattox and Beyond, 94-101; Barbara A. Gannon, The Won Cause: Black and White Comradeship in the Grand Army of the Republic (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 3, 7; “More of Tuttle’s Record,” New York Times, July 24, 1874 (transcribed here); Joseph Cabell Breckinridge Diary, April 2, 1897-November 12, 1897, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; The Rockville Tribune (Rockville, Indiana), December 23, 1908, April 28, 1914; The Baltimore Sun, April 19, 1901; Henry V. Morris (William A. Ellis, Norwich University: Her History, Her Graduates, Her Roll of Honor (Concord, NH: Rumford Press, 1898), 237. For more on the memory of the Civil War, see Caroline E. Janney, Remembering the Civil War (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2013).

[19] William Evans Davies, Patriotism on Parade:The Story of Veterans' and Hereditary Organizations in America, 1783-1900 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1955), 2, 29-30, 42, 75-76, 101; Hibbard Gustav Gumpert, “History of the Loyal Legion,” courtesy of the archives of the Union League of Philadelphia; William Pencak, “MOLLUS—Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States,” in The Encyclopedia of the Veteran in America, vol. 1 (ABC-CLIO, 2009):291-92.

[20] Merrill Edward Gates, Men of Mark in America, Vol. 1, (Men of Mark Publishing Co., 1905), 175; “Main Index to the Companions of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States,” Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, accessed on June 24, 2019 (http://suvcw.org/mollus/orgmem/Index.htm).

[21] William B. Kurtz, “‘Neglected Alumni’: UVA’s Union Soldiers and Sailors," UVA Unionists (http://community.village.virginia.edu/unionist/node/510).