Narratives of African American men in the Civil War usually begin in 1863, with the establishment of the Bureau of Colored Troops and the Federal push for the enlistment of Black soldiers into the Union army. For Black men in Louisiana, however, involvement began over two years earlier, with the formation of a Confederate militia to be drawn from the state’s significant population of free men of color. They were called the First Native Guards. This organization would disband a year later when New Orleans fell to Union forces, but some of the men who had served in the militia would go on to become the first Black soldiers to enlist in the Union army in 1862. They were designated the Louisiana Native Guards, and their service became a litmus test of Black soldiers’ suitability for military participation in the Civil War. Black Louisiana regiments were faced with significant hardship throughout and after the war, including inadequate supplies, hostile reactions from White civilians and fellow Union soldiers, the forcing out of Black commissioned officers, and insufficient pensions. Despite these challenges, the soldiers persevered and demonstrated that if given the chance to fight for their freedom, they would do so admirably.

There were at least ten men born in Albemarle County that enlisted in the Union army in Louisiana. Three of them enlisted at the beginning of the Louisiana Native Guards’ service: Miles Lucius, Stephan Washington, and Horace Washington. These were likely the first three men from Albemarle County that enlisted in the Union army. There are also five who enlisted after the Native Guards’ designation changed to the Corps d’Afrique. We know a good deal about the lives of three of these five, Horace Barlow, Aaron Burr, and William Cary, because of the pensions they filed after the war. The other two men who enlisted in the Corps D’Afrique were Joseph Yates and Joshua Anderson. Finally, Estin Bon and Willis Carr, enlisted in Louisiana in late 1864 after the Corps d’Afrique units had been renamed with standardized U.S. Colored Troop designations. The regiments that the Virginia-born men joined would go on to participate in some of the most significant operations in Louisiana, including the battles of Port Hudson and Fort Blakely as well as the Red River Campaign.

Before any Black Louisianans entered Union service, however, there were the original Native Guards. On April 21, 1861, an article ran in The Daily Picayune, a New Orleans newspaper, calling for the organization of a regiment of local free men of color to join in defense of their Confederate community. Within two weeks, Governor Thomas D. Moore accepted them into the Louisiana Militia. There were a number of reasons that free African Americans in New Orleans entered into this fraught relationship with a state waging war to guarantee the enslavement of their race. Fear for their property, lives, and families was chief among them, and many felt they had no choice but to enlist after being summoned. Whatever their reasoning, they would defend their community for a year before disbanding in April 1862 when Union forces took New Orleans. Shortly thereafter, officers from the Native Guards would approach Union leadership with an offer of service. Despite initial resistance, General Benjamin F. Butler’s official call for their enlistment came on August 24, 1862. Black Louisianans were far more enthusiastic about fighting for the Union cause than they had been about joining the militia. General Butler claimed that within ten days of his order, 1,000 men had enlisted, and this number would continue to grow as the first Black regiments officially entered the Union army.

The 1st Louisiana Native Guards Infantry Regiment mustered in on September 27, 1862. Soon after, the Louisiana Native Guards added two additional infantry regiments – the 2nd on October 12 and the 3rd on November 24. Though the initial call was for free men, regiments were increasingly composed of runaway slaves who had fled behind Union lines during the occupation of New Orleans. Two of the men from Albemarle County, Miles Lucius and Stephan Washington, enlisted in the 3rd Louisiana Native Guards at its initial organization. Lucius was born in around 1823 and Washington in around 1833, both in Charlottesville. They enlisted in Bayou Lafourche and entered Company A as privates. A few months later the 4th Louisiana Native Guards Infantry Regiment mustered in, which also enlisted a Virginia-born soldier in its first days of service. Horace Washington, born in Albemarle County around 1838, enlisted on February 16, 1863 and entered Company C as a corporal. He would spend just three months with the regiment before dying of illness in Baton Rouge.

As the first regiments of the Native Guards began their training, the sentiments of White Louisianans became increasingly hostile. On July 30, 1862, an article titled “The Negro Enlistment Scheme” ran in The Times Picayune, in which the authors deplored the enlistment of “a servile and inferior race,” and claimed that it was “destined, like all illegitimate and unnatural resorts in war, or in any other matters, to ensure to the injury of the party that invokes such aid in a political struggle between two great sections.” Verbal harassment of both the soldiers and their families was common, and rising tensions resulted in physical altercations between Black soldiers and White citizens of New Orleans. Many White soldiers in the Union were also reluctant to accept the Black regiments as their equals or especially, in the case of Black officers, as their superiors.

In the face of the racial turmoil surrounding their enlistment, the soldiers of the Native Guards began to carry out their duty. The army intended to use them primarily in non-combat roles such as building, digging, and clearing land, as many Union officers held the same prejudices as the citizens of New Orleans. Several months after the first regiments mustered in, however, some were given the first real chance to prove their combat abilities. On May 23, 1863, the 1st and 3rd Regiments joined other Union forces under the command of Major Geneneral Nathaniel P. Banks at Port Hudson, Louisiana, where they were attempting to overtake the Confederate stronghold. General Banks ordered a full assault on Rebel forces on May 27. The Native Guards led a brave, but chaotic charge before falling back with numerous casualties, largely due to incompetent direction from Brigadier General William Dwight, Jr., who was drunk. This was one of several failed assaults on the Confederate line that day, and a temporary ceasefire was called so that the men could tend to their dead and wounded. Union forces then commenced a lengthy siege on Port Hudson, with steady gunfire peppering the stronghold for over two weeks until General Banks ordered another all-out assault on June 14. This second attack was also a failure, although this time the men of the Native Guards were held on reserve. The siege continued until July 9, when Confederate Major General Franklin Gardner surrendered, two days after word reached Port Hudson of the Union victory at Vicksburg up the Mississippi.

Despite their somewhat disastrous involvement in the May 27 assault, the overall impression of the ability of the Native Guards was a positive one. General Banks lauded their bravery in personal letters and northern newspapers printed exaggerated tales of numerous heroic charges. James Miller, a Union soldier quoted in James G. Hollandsworth’s The Louisiana Native Guards, wrote in his diary that “all accounts are [that] the Negro fought well, bravely begging their chance to lead the charge.” The performance of Black soldiers in their first major combat engagement validated their service in the eyes of many previously skeptical Unionists.

The Siege of Port Hudson and the beginning of the shift in public opinion coincided with General Banks’s efforts to expand African American military service in the Department of the Gulf. To this end, the Corps d’Afrique was established on May 1, 1863. Under the new title, the Corps d’Afrique would create more regiments and restructure the existing Louisiana Native Guards. The change in designation for existing regiments took effect on June 6, 1863, when Lucius and Washington became privates in Company A of the 3rd Corps d’Afrique Infantry Regiment. William Cary enlisted in the Union army in Louisiana soon after the change, although due to some persisting fragmentation in designations he did not join a Corps d’Afrique regiment. Cary enlisted in the 10th Louisiana Regiment Infantry (African Descent) on August 8, 1863. Horace Barlow and Aaron Burr also enlisted in the Corps d’Afrique around this time.

Horace Barlow was born in about 1828 in Albemarle County. By the mid 1850s, Barlow had entered a slave marriage with Georgianna “Ann” Wilson and they had moved together to Louisiana. He was an enslaved laborer during this time and worked as a brickmaker, though his owners are unknown. His actual surname was Barber, but he enlisted under the name Barlow – a name he and Ann would continue to use throughout and after the war. He enlisted in the 1st Corps d’Afrique Engineers Regiment on April 10, 1863, in Carrolton, Louisiana, at the original organization of the regiment. It is possible that he participated in the Siege of Port Hudson; the 1st Corps d’Afrique Engineers participated in the assault soon after being mustered into service.

Aaron Burr was born in about 1827 in Charlottesville. He was a slave before enlisting, first owned by Dabney Gouch, also of Charlottesville. He was later owned by Paul H. Goodloe, who had married Gouch’s granddaughter, Maria. At some point in his life, Goodloe took Burr to Louisiana, where he was sold to a Charles C. Weeks of New Iberia. Burr married Mary Ann Gray and lived on “Alic Plantation,” likely Alice Plantation, near Jeanerette, Louisiana. Mary Ann would later pass away during the war. Burr enlisted in the 25th Corps d’Afrique Infantry Regiment on October 22, 1863, when he was 36.

William Cary was born in approximately 1830 in Albemarle County. He was an enslaved laborer prior to the war, owned by William Perkins of Goochland County, Virginia. By 1840, Cary had moved with Perkins to Jackson, Mississippi. Cary and his wife, Nancy, married on Perkins’s plantation in 1859. In 1863, the pair fled behind Union lines when Sherman’s army moved through Mississippi, shortly before the fall of Vicksburg in July. William then enlisted in the 10th Louisiana Regiment Infantry (African Descent) on August 8 in Goodrich Landing, Louisiana.

As the war progressed into 1864, the presence of African Americans in the Union forces continued to grow. In May, the Bureau of Colored Troops restructured all Black troops in the army to establish consistent numbering of the regiments. With this, the Corps d’Afrique units were again renamed, becoming regiments of the United States Colored Troops (USCT). Washington and Lucius of the 3rd Corps d’Afrique Infantry were now members of the 75th USCT Infantry Regiment, Barlow of the 1st Corps d’Afrique Engineers joined the 95th USCT Infantry Regiment, Burr of the 25th Corps d’Afrique Infantry joined the 93rd USCT Infantry Regiment, and Cary of the 10th Louisiana Infantry (African Descent) entered the 48th USCT Infantry Regiment. Lucius would desert the 75th USCT that same month.

With their new USCT regiments, the Virginia-born men likely saw a number of significant operations in the Gulf Coast region, including the Red River Campaign and the Battle of Fort Blakely. The Red River Campaign took place from March 10 to May 22, during the time of transition into new designations. This complex operation combined army and navy regiments with the goal of taking Shreveport, Louisiana, a major Confederate capital in which the Union sought to establish a base for further expansion into Texas. The campaign consisted of a number of engagements and Union retreats, ultimately concluding in one of the last Confederate victories of the war. The 75th USCT and 84th USCT Infantry Regiments participated in this campaign, although they likely saw little action. Their primary duties included guarding wagon trains and rail lines, strengthening fortifications, and assisting in the construction of a dam that would allow Union ships to navigate the low water levels of the Red River. Around a year later, from April 2-9, 1865, the 48th USCT took part in the Battle of Fort Blakely in Alabama. Black troops played a significant part in this decisive Union victory, which coincided with Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox and the beginning of the end of the war.

The year following Lee’s surrender saw the mustering out of many of the Black Louisiana regiments. Barlow, Cary, and Washington all mustered out along with their regiments, Washington with men he had likely fought alongside for the entirety of his service since joining at the original organization of the Native Guards. Burr completed his term of service a few months before the rest of his regiment officially mustered out. The return to civilian life brought new freedoms and challenges for Black veterans of the USCT, as they adjusted to the hard-fought status that their military service afforded them.

Horace Barlow and his wife, Ann, lived in Eperville Parish after the war before settling in East Baton Rouge, Louisiana. He worked on sugar and rice farms and legally married Ann in 1877 in Iberville Parish. Barlow began receiving a pension of $8 a month in 1901 for “general senility,” before passing away on July 15, 1904, from edema. Ann would then receive his pension until her death in 1913. Horace and Ann were survived by their three children, George, Letty, and Annie.

Aaron Burr moved to Loisel Plantation and worked as a blacksmith after the war. He married Reita Madison in 1866. Burr had two children, likely with Madison, although his pension records are unclear about whether they were with his first or second wife. He began receiving a pension of $6 a month in 1903 for senile disability and hernia. He died of unknown causes on April 19, 1906.

William Cary and his wife, Nancy, moved around a great deal after his mustering out in 1866. It is likely that he and Nancy first moved to Vicksburg, then Louisiana as sharecroppers, then back to Jackson, then Memphis, then finally to the Oklahoma territory where they settled in Arapaho Township. They had four children together, Dolly Ann, Annie B., Ida L., and Mary O.L. Cary suffered from numerous ailments including rheumatism, disease of the rectum, senile debility, muscular contractions, disease of the lungs, and disease of the spine. As a result, he began receiving a pension of $10 a month in 1900. He died in Arapaho Township on March 8, 1902 of unknown causes. Nancy received a widow’s pension after his death and by the time she passed away on February 25, 1939, she was receiving $50 a month.

The frequent changes in regiment designations and leadership can make the history of these men and their service seem fragmented; however, the consistent impact of African American military service in Louisiana should not be overlooked due to bureaucratic flux. It was in Louisiana that Black men in the Union were given one of the first opportunities to prove themselves, months before the Emancipation Proclamation and a year before the formal establishment of a Bureau of Colored Troops. Throughout the course of the war they would continue to blaze trails, performing well above the racist expectations of their abilities. The men from Virginia embodied this spirit, some fleeing behind Union lines after lifetimes of slavery for the chance to fight for their freedom. Many of the soldiers about which we have detailed information were able to live long lives with their families as free men after the war. They received some of what they were due through pensions, although rarely were they afforded the same respect and economic support as White veterans. Overall, African Americans’ participation in the Civil War in Louisiana, from militia to the USCT, was a testament to their bravery and persistence in the face of poor treatment, extreme hardship, and a nation that was reluctant to recognize their clearly demonstrated capabilities.

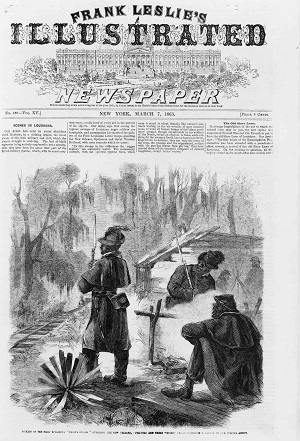

Images: (1) “Pickets of the First Louisiana ‘Native Guard’,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, March 7, 1863 (Courtesy Library of Congress); (2) Louisiana Native Guard at Port Hudson (courtesy Wikicommons); (3) “Siege of Port Hudson,” and (4) “Building the Red River Dam” (both courtesy Library of Congress); (5) Excerpt from Aaron Burr's Pension Application (courtesy National Archives).

Compiled Service Records for Horace Barlow, Aaron Burr, William Cary, Miles Lucius, Horace Washington, and Stephan Washington, RG 94, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Accessed through Fold3 (https://www.fold3.com/browse/273/); Pension records for Horace Barlow, Aaron Burr, and William Cary, RG 15, National Archives and Records Administration; Arthur W. Bergeron Jr., ed., The Louisiana Purchase Bicentennial Series in Louisiana History, vol. 5, The Civil War in Louisiana (Lafayette, LA: The Center for Louisiana Studies, 2002); “Battle of Fort Blakely,” American Battlefield Trust, accessed November 19, 2018, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/fort-blakely; Ira Berlin, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie S. Rowland, eds., Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation 1861-1867: Selected from the Holdings of the National Archives of the United States, Series 2, The Black Military Experience (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982); Nathan W. Daniels, Thank God My Regiment an African One, Ed. C.P. Weaver, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press: 1998); William A. Dobak, Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, 2011); Frederick A. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion, vol. 3 (New York: T. Yoseloff, 1959); Phillip Faller, “Siege of Port Hudson,” American Battlefield Trust, Accessed November 19, 2018, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/siege-port-hudson; “Fort Blakely,” American Battlefield Trust, Accessed November 19, 2018, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/fort-blakely; Lawrence Lee Hewitt and Arthur W. Bergeron Jr., eds., Louisianans and the Civil War (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2002); James G. Hollandsworth, The Louisiana Native Guards: The Black Military Experience During the Civil War, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1998); Ludwell H. Johnson, Red River Campaign: Politics and Cotton in the Civil War (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1993); Gary D. Joiner, Through the Howling Wilderness: The 1864 Red River Campaign and the Union Failure in the West (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2006); “The Negro Enlistment Scheme,” The Times-Picayune,” July 30, 1862, Accessed through Newspapers.com; Stephen J. Ochs, A Black Patriot and a White Priest: André Cailloux and Claude Paschal Maistre in Civil War New Orleans (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000).