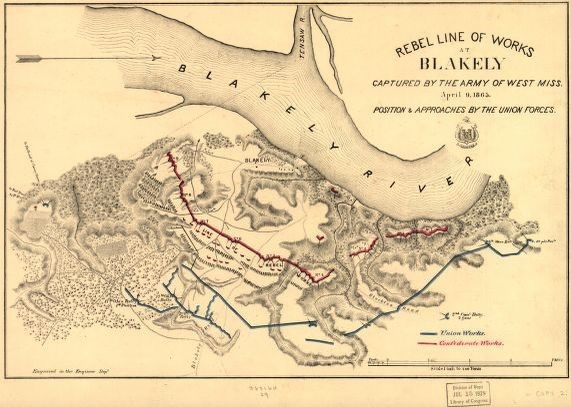

The Battle of Fort Blakeley in Alabama took place in early April 1865 as the Civil War drew to a close, motivated by the Union desire to drive the Confederates out of their final holdings near the Gulf Coast. The seaport of Mobile Bay was no longer under Confederate control, but the city of Mobile itself still was, protected by the Confederate posts of Spanish Fort, directly to the east across the bay, and Fort Blakeley, about six miles to the north. In the end, nearly 16,000 Union soldiers fought to regain the fort, including some 5,000 members of the United States Colored Troops (USCT). This makes the assault on Fort Blakeley one of the battles with the largest proportion of USCT soldiers participating during the war.[1]

Nine African American soldiers present at the Battle of Fort Blakeley hailed from Albemarle County, Virginia: George Atkinson, Patrick Henry Atkinson, Jackson Hickenberger, Isaac Price,[2] Nathaniel Thomas, William Turner, Samuel Williams, and Joshua Wells, who all served in the 68th USCT Infantry Regiment, and William Cary of the 48th USCT Infantry Regiment all took part in the last major battle of the Civil War. Although most survived the fight unscathed, the sacrifice and suffering of those among the nine who did not is tinged with a particular tragedy given that the final assault of the battle on April 9 occurred hours after the surrender of General Robert E. Lee to General Ulysses S. Grant. Of the nine, this post will focus on George Atkinson, Patrick Henry Atkinson, William Turner, and Joshua Wells.

Prior to the war, the Atkinsons, Turner, and Wells all lived in Missouri, despite having been born in Albemarle. For the most part, Albemarle-born USCT soldiers who lived in Missouri prior to the war did so as a result of their Virginian owners moving across the country and forcing their enslaved workers to move with them. This is true of George and Patrick Henry Atkinson. Although the specific relationship between the two men is unknown, both were enslaved workers of John Atkisson, who moved them with him to Benton County, Missouri, and owned 26 enslaved workers in 1860. George was a twenty-five-year-old farmer when he enlisted in Company I of the 68th USCT Infantry Regiment on February 17, 1864. Patrick’s journey to joining the USCT was more eventful in that he claimed to have assisted Union forces prior to his enlistment. While seeking a veteran’s pension, he testified that in 1862 he had been shot in an ambush by Rebels as he drove a Union team from Cole Camp to Warsaw, Missouri. A year later while working as a slave in Warsaw, then occupied by “the Rebels,” he claimed to have been shot in the right shoulder by attacking Federal forces. These injuries were not severe enough to prevent him from enlisting in Company D of the 68th at the age of twenty on February 24, 1864.[3]

William Turner was enslaved near the Atkinsons in Pike County, Missouri. He was older than the Atkinsons, born on April 1, 1832 (some sources say 1828) in Albemarle, and had married a woman named Dollie Winston, although the union was not legally recognized since both Dollie and William were enslaved. They had fourteen children over the course of their marriage, but several died in childhood. Turner enlisted in Pike County on March 14, 1864, joining Company F of the 68th USCT.[4]

Joshua Wells differs from the Atkinsons and Turner, and the other five Albemarle-born African American soldiers present at Fort Blakeley in that it is unclear if he was enslaved when he volunteered to serve the Union in Company H of the 68th USCT. He enlisted on May 6, 1864, and was described as five feet, five inches tall, with black hair, eyes, and complexion in his service record. He was a farmer, residing in Ashley County, Missouri, at the time of his enlistment.[5]

In addition to these four men, the 68th USCT contained fifteen more men who were born in Albemarle, though not all were present for the Siege of Fort Blakeley.[6] Initially based in Benton Barracks, near St. Louis, Missouri, the unit was originally formed as the 4th Missouri Colored Infantry Regiment before being reorganized in March 1864. Benton Barracks was notoriously unhealthy due to cramped living conditions and the hot, swampy environment, and four of the nineteen Albemarle-born men of the 68th USCT died of disease while there. One such casualty was Henry Atkinson, who died of smallpox. Prior to his enlistment, he had been owned by John Atkisson along with George and Patrick Henry Atkinson.[7]

After organizing at Benton Barracks, the 68th USCT was ordered to Memphis, Tennessee, to defend the Union-controlled city and was stationed at nearby Fort Pickering until February 1865. From there, the regiment was ordered to New Orleans to join the 1st Brigade of the 1st Division USCT, then part of the Military Division of West Mississippi, under the command of Major General Edward R. S. Canby. In March 1865, Union Major Generals Canby and Frederick Steele began their final campaign to retake Mobile, Alabama. Steele and his column of forces would move up and around from Pensacola to begin the attack on Fort Blakeley from the northwest, and Canby’s command would travel north along Mobile Bay to begin the siege of Spanish Fort from the south. Additional troops were necessary to carry out the siege, so the 68th USCT, along with several other USCT regiments, was called from New Orleans to Barrancas, Florida, near Pensacola, where it would join the 1st Division of the USCT. The men would spend three weeks there training, a necessary delay as historian William A. Dobak notes that the 68th USCT also had previously carried out non-combatant work at the command of Brigadier General J. C. Veatch when the regiment was “detailed exclusively for engineer duty until further orders” just a few months earlier. Even the regiment’s commander, Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Densmore, was unsure of the assignment and wondered why “mere laborers” were specifically called upon for the battle as opposed to soldiers more experienced in combat.[8]

The 68th USCT left on foot for Fort Blakeley in the middle of March. It was a difficult journey, due to a lack of resources and unpleasant weather. Colonel Densmore reported on the conditions experienced by his forces:

On horseback it was a fair march… But on foot the day had a different aspect. Under a knapsack on which a woolen blanket, and a rubber [blanket], and a shelter tent, and a hot sun are bearing… there is less leisure & less spirit…

Later, Patrick Henry would claim to have developed lumbago and rheumatism “incurred as a result of hard marching Pensacola Florida to Fort Blakely Ala in 1865.” The men arrived toward the end of the month, and were attached to the XVI Corps in time for the start of the siege on April 1.[9]

As Canby fought to surround Spanish Fort, he sent a detachment including the 68th USCT north to support Steele’s efforts at Fort Blakeley, by taking up the rightmost position in the line of Union advance. Almost immediately upon their arrival on April 1, they were ambushed by Confederate forces hidden in the woods on the high ground. The regiment nevertheless succeeded in pushing the attackers back, overtaking the high ground and the swamp on the other side until they were only one hundred fifty yards away from the Confederate defenses—a line which the men of the 68th USCT fought hard to maintain over the next week, since it was the point most vulnerable to Confederate counterattack. Meanwhile, other units of both Black and White soldiers saw success as they continued to surround the Confederate post, including William Carey’s 48th USCT.[10]

After the initial skirmish, the men present began to dig trenches around the fort, with a basic system finished by the morning of April 3. These trenches provided protection from shelling by Confederate gunboats called into Mobile Bay, and eventually encircled both Spanish Fort and Fort Blakeley in a continuous Union line. The ground was still hard in early April and required a determined effort to break as the “men of the Colored Troops Division found regiments of the [White] XIII Corps assisting them with digging and construction” of the siege lines.[11]

Fighting continued periodically until the word came on April 9 that Spanish Fort had fallen the night before, freeing Canby and his troops to assist Steele in the final seizure of Fort Blakeley. Around 4 pm on April 9, permission was granted for the line of Union forces to advance and launch an attack on the enemy. The 68th USCT, along with other USCT regiments, was instrumental (and enthusiastic) in clearing the front line of Confederate forces. Eventually, with the help of Canby’s men, the Union army executed a final charge on the fort, with troop movement beginning on the left and sweeping across to the right. The main line of defense was breached, and the post was captured swiftly. “Many of the enemy… threw down their arms and ran toward their right to the White troops to avoid capture by the colored soldiers, fearing violence after surrender,” stated Brigadier General William A. Pile, the commander of the 1st Brigade, 1st Division USCT in a report. Three days later, on April 12, the mayor of Mobile formally surrendered the city.[12]

The 68th USCT bore a disproportionate share of the casualties suffered among the nine USCT regiments at the Battle of Fort Blakeley. Of the one hundred men of the 68th USCT killed and wounded during the siege, two were born in Albemarle. Joshua Wells suffered a musket ball to his groin on April 7, likely in a pre-dawn attack from the Confederates remaining in the garrison as they charged the Union’s XVI Corps, of which the 68th USCT was a part. Historian and fellow Union soldier C. C. Andrews wrote that the Confederates came upon the Union troops “in strong force, delivering repeated volleys, and charging with cheers up to the pits of the federals.” Ultimately, though, the Confederate forces were repelled. The second man from Albemarle hurt in the battle was Corporal George Atkinson, who was mortally wounded on April 9 and died the next day. Both tragic, Atkinson’s sacrifice is particularly important to note within the context of the larger scope of the Black Virginians in Blue project, as only five of the 257 Black Union soldiers from Albemarle died in combat. [13]

After the battle, Joshua Wells’s injury suffered proved serious and he was discharged for disability at the rank of private on June 24, 1865, in Greenville, Louisiana. Patrick Henry Atkinson and William Turner, however, remained with the 68th USCT, which marched to Montgomery, Alabama, after briefly occupying the city of Mobile. In June of 1865, the regiment moved to New Orleans and then into Texas, where it carried out duty along the Rio Grande until February of 1866, when both Atkinson and Wells were mustered out from Camp Parapet, Louisiana. By the end of their service, Atkinson had attained the rank of sergeant, and Turner the rank of corporal—remarkable, given the relatively few opportunities for advancement available to Black soldiers, who were generally denied entry into the commissioned officer ranks.[14]

Atkinson, Turner, and Wells all returned to Missouri and each filed for invalid pensions in compensation for their wartime injuries. Atkinson began a new life as a preacher and married his wife, Caroline, in 1866, with whom he had two children, Patrick Henry and Rose Lee. Atkinson applied for an invalid pension in 1891, receiving $8 a month for “lumbago and disease of rectum and right foot,” eventually increasing to $16.50 before his death by heart disease and chronic nephritis in 1913 in Moberly. Upon his death, Caroline Atkinson applied for a widow’s pension, and was receiving $50 a month from the Pension Office by 1926. She continued to collect the pension and lived to be 105 years old, dying of chronic interstitial nephritis in 1946.[15]

For William Turner, postwar life meant a reunion with his wife and several children in Pike County and his slave marriage to Dollie was legitimized in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. He and Dollie remained close with his family, at first living with Turner’s parents and brother, and then with some of their children and grandchildren. Turner received a pension beginning in 1890 for rheumatism and an injury to his eye suffered on a march from St. Louis to Memphis. The Pension Office eventually granted him a $38 per month pension. He died under the care of his daughter, Georgianna, in 1924 at her home in Clarksville.[16]

Joshua Wells started a family after his service, meeting Lucinda in Pike County and marrying her in 1868. Testimony revealed that both Wells and Benson had been previously married, but the names of the prior spouses are not known. It is unclear if Wells’s one child, a son named James, was also Luncinda’s or Wells’s from his previous marriage. He continued to suffer from the gunshot wound he received at the Battle of Fort Blakeley and he applied for a pension to compensate for the injury in 1871. Four years elapsed between his application and its approval at only $2 per month, although he was granted back pay to 1865. He continued to receive a pension until his death in 1884, at which point his wife applied for and was granted a widow’s pension until her death a decade later in 1894.[17]

Although overshadowed in public knowledge by the simultaneous surrender of General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox, the Battle of Fort Blakeley was an important demonstration of the critical role of USCT soldiers in securing the Union’s ultimate victory. Though originally consigned to duty as laborers far from battlefield, the service and sacrifice of George Atkinson, Patrick Henry Atkinson, William Turner, and Joshua Wells in the 68th USCT helped secure Fort Blakeley and Mobile, Alabama, capturing the Confederates’ last stronghold on the Gulf Coast. In the aftermath of the battle, Union officers praised their Black troops’ heroism, with the 68th USCT’s Colonel Densmore stating, “The fighting morale, it seemed to me, would satisfy any commander:” Historian William Dobak summed up their contributions succinctly: “All witnesses agreed that the attack of the Colored Troops Division thoroughly broke the Confederates’ will to resist.”[18]

Images: (1) Rebel line of works at Blakeley (courtesy Library of Congress); (2) Discharge form for George Atkinson, 68th USCT (courtesy National Archives and Records Administration).

[1] Mike Bunn, “Battle of Fort Blakeley,” Encyclopedia of Alabama (2017), http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-3718.

[2] For more on Isaac Price and his family, see Catherine Kolo, “Slave Marriage, Free Marriage: Connecting Military Service to Relationships in Formerly Enslaved Veterans from Albemarle, Virginia,” Black Virginians in Blue (/usct/node/557).

[3] Compiled Service Record for George Atkinson and Patrick Henry Atkinson, RG 94, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Washington, D.C.; Pension Records for Patrick H. Atkinson, RG 15, NARA, (transcript available at /usct/node/538); John Atkisson, United States Federal Slave Schedules, 1860, accessed through Ancestry.com.

[4] Compiled Service Record for William Turner, NARA; Pension Record for William Turner, NARA.

[5] Compiled Service Record for Joshua Wells, NARA.

[6] Several of the men in the 68th were enslaved workers of Virginian John Coles Carter. For their stories, see Elizabeth R. Varon, “From Carter’s Mountain to Morganza Bend: A U.S.C.T. Odyssey,” Black Virginians in Blue (/usct/node/25).

[7] Compiled Service Record for Henry Atkinson, NARA. To learn more about environment and disease as causes of death for Albemarle-born USCT soldiers, see Sarah Anderson, "Quite Unhealthy": Deadly Diseases Among Albemarle-born Black Soldiers,” Black Virginians in Blue (/usct/node/93).

[8] Frederick A. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion, vol. 3 (Des Moines, IA: Dyer Publishing Company, 1908), 1734, accessed on National Park Service Soldiers and Sailors Database (https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-battle-units-detail.htm?battleUnitCode=UUS0068RI00C); Official Records of the Civil War, Series 1, Volume 48, Part 1 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1896), 421; D. Densmore quoted in William Dobak, Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Army, Center of Military History, 2011), 143.

[9] Densmore quoted in Dobak, Freedom by the Sword, 145; Pension Records for Patrick H. Atkinson, NARA; Colonel Charles W. Drew and Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Densmore in Official Records, Series 1, Volume 49, Part 1 (Washington, Government Printing Office, 1897), 295- 299.

[10] Dobak, Freedom by the Sword, 147-149.

[11] Ibid, 149-150.

[12] Ibid, 150-153.

[13] C. C. Andrews, History of the Campaign of Mobile; Including the Cooperative Operations of Gen. Wilson’s Cavalry in Alabama (New York: D. Van Nostrand Company, 1889), 180-181; Compiled Service Record for Joshua Wells and George Atkinson, NARA.

[14] Compiled Service Record for Joshua Wells, Patrick Henry Atkinson, and William Turner, NARA.

[15] Pension Record for Patrick Atkinson, NARA; 1870 U.S. Federal Census; “Patrick Henry Atkisson,” Certificate of Death, Missouri State Board of Health, Bureau of Visual Statistics, accessed through Ancestry.com; “Patrick Henry Atkinson,” Findagrave.com (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/52685057).

[16] Pension Records for William Turner, NARA; U.S. Federal Census, 1870, 1880, 1900, 1910, 1920; Death Certificate for William Turner; Marriage Record for William Turner and Dollie Winston, accessed through Ancestry.com.

[17] Pension Records for Joshua Wells, NARA; 1880 U.S. Federal Census; Last Will and Testament of Joshua Wells, accessed through Ancestry.com.

[18] Densmore quoted in Dobak, Freedom by the Sword, 149, 153.