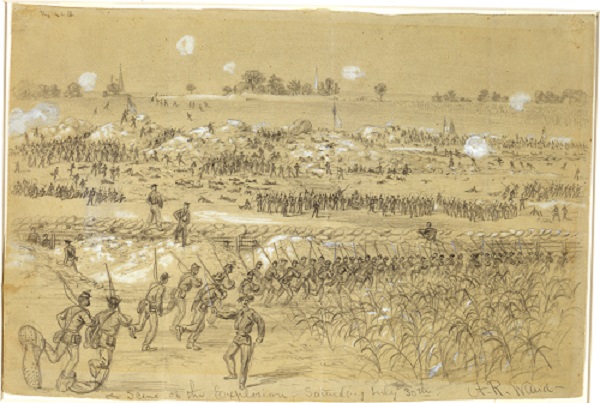

On July 30, 1864, the Union army exploded a mine to expose a breach in Confederate lines at Petersburg in the hope of breaking the stalemate and ending the siege. The ensuing assault, which became known as the battle of the Crater, resulted in a Union failure and thousands of casualties in the worst racial massacre of the war. The Black troops of the United States Colored Troops (USCT) faced much greater danger at the Crater than their White Union counterparts. Following the massacre of surrendering USCT troops and officers at Fort Pillow months earlier, the men of the USCT expected to receive what Lt. Col. John Armstrong Bross of the 27th USCT Infantry Regiment described as “no quarter” from Confederates. Equally as important, because many of the USCT had escaped from their masters to enlist, defeat or capture could mean a return to slavery and a loss of their freedom. Despite the extreme peril, the men of the USCT persisted and served honorably at the Crater and beyond.

Of the Black men serving in the Union army at the Battle of the Crater, at least twelve were from Albemarle County, Virginia. Only eleven likely served in a combat role, with William Harris of the 27th USCT, Co. G, serving as a company cook at divisional headquarters. While little is known about the lives of most of these men, we do know a great deal about three of the soldiers who filed pension records: William Page, 39th USCT Infantry Regiment, Co. F; Henry Kettell 23rd USCT Infantry Regiment, Co. K; and Peter Churchwell 23rd USCT Infantry Regiment, Co. H. Thanks to the research of Cinder Stanton, we also know the story of Daniel Fossett, 27th USCT, Co. B.

Although all four Albemarle County men were born into slavery, they followed different paths to Petersburg. Daniel Fossett was born in 1824 to Joseph and Edith Fossett, Thomas Jefferson’s blacksmith and chief cook respectively. Joseph Fossett became free one year after Jefferson’s death and with the help of the free Black musician Jesse Scott, and the profits from his blacksmith business, managed to buy the freedom of most his family, including Daniel. Daniel moved with his family to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he lived and worked as a blacksmith until he enlisted in the 27th USCT on February 1, 1864, at Hamilton, Ohio.

Peter Churchwell was born in March 1826. Before he served, he moved with his owner, Reuben Gordon, to Orange County, Virginia. He married his first wife Maria on Christmas Day 1857 and had a daughter named Dicey. Peter escaped slavery in August 1862 by running away to Washington, D.C., where he worked as a coachman for a Mrs. Jonathan Barber. He then enlisted in the 23rd USCT, Co. H, on July 13, 1864, in Washington, D.C. Only two weeks later, Churchwell served in the Battle of the Crater.

Henry Kettell (Williams) was born around 1841 in Albemarle County. He lived about thirteen miles away from Charlottesville and was at some point sold as a slave to man likely known as William Kettell along with his brother Edmund Williams. Kettell may have married his first wife Mary (Martha) in slavery before escaping with some of his brothers to Washington, D.C. Kettell enlisted in the 23rd USCT, Co. K, on May 14, 1864. Kettell then travelled to Massachusetts before eventually joining the 23rd in Alexandria and then travelling to Petersburg.

William Page was born in 1839 in Norfolk, Virginia. At some point, Page became the slave of Andrew Stevenson, owner of Blenheim estate in Albemarle County. Stevenson was a former Democratic congressman, Andrew Jackson’s minister to Great Britain, and served on the University of Virginia’s Board of Visitors before being elected rector in 1856 a year before his death. According to his service records, Page worked as a waiter before the war. He enlisted in the 39th USCT, Co. F, on March 30, 1864, in Baltimore, Maryland. After a brief stay in the general hospital in Annapolis, Page rejoined the 39th USCT in time to participate in the Overland Campaign from the Rapidan to the James River in Virginia. Page and the 39th guarded the army’s wagon trains. The 30th USCT Infantry Regiment, which would fight with the 39th USCT at the Crater, also served in the rear on guard duty, fending off Confederate cavalry twice between the Wilderness and Cold Harbor. Additionally, George Bouldin, Thomas Parker, and Martin Reeves served with Kettell and Churchwell in the 23rd USCT. Richard Brown served with Fossett in the 27th USCT. Daniel Lucas, Adam Walker, and Mattison Watson served with John H. Hopkins of the 30th USCT at the Crater.

In preparing for the detonation of the mine and the assault on Rebel lines, the IX Corps of the Army of the Potomac, under the direction of Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, ordered the 4th Division, under Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero to lead the attack. The 4th Division was comprised of two brigades of USCT troops. The first, led by Lt. Col. Joshua K. Sigfried included the 27th USCT, 30th USCT, 39th USCT, and 43rd USCT. The second brigade, under Col. Henry Goddard Thomas included the 19th USCT, the 23rd USCT, the 29th USCT, and the 31st USCT. The USCT regiments were comparatively fresher than their White comrades having not yet experienced combat. This lack of experience, however, convinced Burnside the Black troops could overcome their White counterparts’ hesitant belief that the Confederate entrenched positions could not be taken. But the day before the attack, Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade forbade Burnside from using the USCT troops, thinking the Black troops inferior soldiers and fearing the political fallout of failure.

Leading up to the attack on July 30, the Albemarle men’s regiments participated in at least some preparation for the impending assault. Men of the 23rd USCT assisted Lt. Col. Henry Clay Pleasants in the constructing of the mine, carrying out dirt in sacks and hauling timber for framing the mine gallery’s sides. There are conflicting reports detailing the amount of drilling the USCT regiments conducted prior to the attack. Some reports describe how the 30th and 43rd USCT “drilled intensively” to prepare for leading Lt. Col. Joshua A. Sigfried’s attacking brigade. Col. Delevan Bates of the 30th USCT, however, described little to no drilling prior to the attack following the mine explosion, as he had not even known about the mine until July 22.

Despite the lack of training, the men prepared for battle. Colonel Bates described men of the 30th USCT like Lucas, Walker, Watson, and Hopkins anticipating a “great event” the following day, turning to the regimental chaplains for support and inspiration. Although the men of the USCT expected no quarter from Rebel forces, they remained defiant. During training, the 30th USCT often sang the song (as quoted in Richard Slotkin’s No Quarter):

Jeff Davis says he’ll hang us,

If we dars to meet him armed

Beery Big t’ing, but be not t’ht all alarmod;

For fust he’s got to gotch us

Dat am berry clar’r;

And dat’s what’s de matter

Wid de Colored Voluntar.

Following the mine explosion 4:45 AM on July 30th, Burnside ordered the all-White Second and Third Divisions forward, but the Confederate artillery batteries repelled the attack. At 7:30 AM as a last resort, Burnside ordered the Colored Division to attack and salvage the operation. The attacking regiments of the USCT faced much greater peril then the previous White troops. They lacked the element of surprise that supported the Second and Third Divisions, had to move through a mass of demoralized White union troops, and faced a significantly reinforced enemy. The brigade initially found success, with the 30th USCT under the command of Bates at the head of the column capturing a reported 250 prisoners, 200 yards of trench, and one flag. As the column further advanced, however, the Rebels’ artillery and guns bombarded the men. A single round of canister killed half of the 30th USCT’s color guard in an instant. With the steadfast Confederate resistance, the advance stalled.

After Bates’s attack was repulsed, the other men received orders to advance. Lt. Col. Bross and other officers managed to separate the men of the 23rd and 29th USCT from the mass of retreating White Union troops who had failed to advance in Burnside’s earlier attack and ordered the Black troops forward. Col. Bross grabbed the regimental colors of the 29th USCT, encouraging the men to “show the world today that the colored troops are soldiers.” Bross then charged further into the breach, leading nearly 400 troops of the 23rd USCT. A Confederate counterattack at the same time cut down Bross and dozens of his regiment’s men. Of the 400 men who followed Bross, only 128 returned to Union lines, with the rest killed or captured.

As the men of the USCT retreated, many faced the merciless violence of the Rebel forces. The Confederates kept their promises of no quarter, executing and slaughtering great numbers of wounded soldiers and POWs under escort. One estimate posits that fewer than half of the USCT prisoners made it to the rear to avoid murder. Pvt. Isaac Gaskins of the 29th USCT was taken prisoner by a Confederate soldier who later told Gaskins he would have killed him if not for the blood covering his face concealing his race. The White officers of the USCT faced poor treatment as well. Following the battle, the Confederate captors paraded the White officers and Black enlisted men of the USCT who survived the slaughter through the streets of Petersburg to suffer a jeering crowd, despite many of the troops missing clothes and suffering from grave wounds.

During the charge of the Rebel lines, Peter Churchwell of the 23rd USCT was hit by Rebel fire to his right foot, the left side of his head, and his right eye. Badly wounded, he was soon captured by Confederate soldiers. The army incorrectly considered him dead following the battle, allowing his mother to receive a pension of $8 a month beginning in 1868 on behalf of his minor daughter Harriet. Surprisingly, the Confederate troops did not execute Churchwell and instead forced him and other prisoners to bury the dead for four days. The Confederates then imprisoned Churchwell at Danville prison at Roanoke Island, North Carolina. Churchwell’s former master Gordon claimed him as his slave, resulting in a series of men purchasing and selling him until he ended up as an enslaved shoemaker for a Patrick Murphy near Raleigh. After six months of work, Churchwell escaped to the Union-held Wilmington and maintained his freedom.

Many White Northerners tried to blame the failure of the Crater on the race of the USCT soldiers. USCT officers’ testimony, however, seems to exonerate the men, with Capt. Robert Beecham of the 23rd USCT claiming the chaos of the battle would have confused “anything but the best-drilled troops.” The Black community responded in support lauding the efforts of the USCT in the press, using their noble service at the Crater as a recruiting tool. After the war, Sgt. James H. Payne of the 27th USCT called the brigade’s advance past the Crater “one of the most daring charges ever made since the commencement of the rebellion.”

Following the disastrous slaughter at Petersburg, the USCT regiments and the Albemarle men who served within them continued to fight for the Union cause. The 23rd USCT served duty on the Bermuda Hundred front and participated in the Appomattox campaign where they were present for Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House. The 27th, 29th, and 30th USCT saw combat following the Crater including the assault and capture of Fort Fisher, North Carolina, the capture of Wilmington, and finally were present for the surrender of Johnston and his army. The 27th and 30th USCT served in North Carolina until their men were mustered out in September and December respectively. The 39th USCT also served in North Carolina and mustered out in December. The 29th and the 23rd USCT, however, ended the war by serving garrison duty in Texas until mustered out in November.

Black veterans continued to face greater hardship then Whites after their service. Compared to the non-veteran population, a disproportionate number of USCT veterans lived in or moved to northern states or southern cities and worked in higher status jobs. The majority of Black veterans, however, lived in rural poverty. Many attempted to reunite or establish families, legalizing marriages made in slavery or taking their fathers’ last names instead of their former masters’. A great number of Black veterans enjoyed better lives than those that did not serve, receiving government benefits from claims for unpaid wages, federally supported veterans’ homes and, crucially, pensions. Despite the assistance afforded by pensions, Blacks still received an inequitable amount of welfare through pensions relative to Whites. Black veterans faced many obstacles in applying for pensions, including, poverty, illiteracy, changed names or identities, distant or unreachable former comrades and officers, the greed of predatory claims agents and lawyers, and the racism of special investigators and pension bureau workers.

Peter Churchwell remained in Wilmington for several years, operating a successful shoe shop and building a family with second wife Susannah Dean with whom he would have two daughters, Nancy Ann and Hetty Ann. A domestic dispute in 1870 caused Churchwell to leave his family and reconnected no later than March 1874 with his daughter Harriet in Washington, D.C. There, he continued work as a shoemaker, married his third wife Julia Parker Weaver, and regained his pension. Churchwell began receiving a pension $6 a month in the late 1890s for rheumatism, senile debility and heart disease that increased to $12 a month by 1898. He died January 14, 1902 in and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Following the war, many of Churchwell’s fellow veterans from Albemarle led similar lives. After recovering in the general hospital in Alexandria, Virginia, Henry Kettell, like Churchwell, returned to Washington, D.C. Kettell worked as a laborer, contracting at one point for someone named Lacey. He lived with his first wife Mary until her death in 1884 and later married his second wife, Sarah Catherine Elizabeth Williams at the Fourth Baptist Church in D.C. Kettell continued to suffer from the gunshot wounds from the Crater, as well as rheumatism, heart disease and Parkinson’s disease. He began receiving a pension of $8 a month starting in 1890 backdated at $2 a month to 1865. Henry Kettell died of heart disease and dropsy on February 26, 1899, in Washington D.C. and, like Churchwell, is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

William Page returned to Virginia, settling in Blenheim, Albemarle County, as a farmer. Page married his second wife, Catherine Waters and had four children, named William C., Anna M., Jonathan, and James Page. Because of his service, he suffered rheumatism of the legs, throat trouble, shortness of breath, impaired vision, and partial deafness. As a result, he received a pension of $12 a month commencing in 1890, which increased to $20 a month by 1910. He died of unknown causes on May 26, 1910, in Blenheim. His widow Catherine faced great difficulty receiving a pension due to a marriage from a previous husband complicating the application process. Nonetheless, she received a pension that increased to $30 a month by the time of her death in 1921.

If, as seems probable, the Daniel Fossett of the 27th USCT is in fact the Daniel Fossett of post-war Cincinnati references discovered by Cinder Stanton, he had a difficult life following his service. Fossett returned to Cincinnati after the war. In January of 1866, Fossett was tried in a case of grand larceny for the allegation of stealing around $50 of property from a man named Jones. On October 9, 1872, while walking up the stairs to the room of a Victoria Smith, she and Fossett fell down from the landing to the ground after a brief altercation over a two-dollar bill. Fossett died from head injuries he sustained in the fall. Victoria survived but was permanently injured. According to the Cincinnati Daily Enquirer, Fossett left behind an unnamed wife and child.

The experience of Albemarle’s Black Union soldiers at and after the battle of the Crater illustrates the greater danger and hardship faced by the men of the USCT. Racially motivated incompetent leadership forced the 4th Division into an unwinnable situation at the Crater and into a horrible massacre upon failure. Even after the Civil War, Black veterans faced barriers of institutionalized inequality, racism, and often-inescapable poverty. Despite such hardships, the men and veterans of the USCT endured. The USCT proved valuable to the war effort, continuing to shift the tide of the war and contributing to the fall of Richmond, Petersburg, Wilmington, Raleigh, and other Southern strongholds. After the war, the men built lives for themselves often using helpful, albeit unequal, pensions for their service. Men like Peter Churchwell persevered, going from an early life in slavery to a successful business career in the nation’s capital.

Images: (1) Alfred Wauld, “Battle of the Crater” (courtesy Library of Congress & Wikicommons). (2) Excerpt from Daniel Fossett’s enlistment papers (courtesy National Archives). (3) “John A. Bross,” from Arthur Swazey, Memorial of Colonel John A. Bross, Twenty-ninth U.S. Colored Troops… (Chicago: 1865). (4) “Captured Negroes,” August 27, 1864, The Richmond Dispatch. (5) Peter Churchwell’s and Henry Kettell’s graves, Arlington National Cemetery (photographs taken by William B. Kurtz).

Compiled Service Records for Peter Churchwell, Daniel Fossett, Henry Kettell, and William Page, RG 94, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., accessed through Fold3 (https://www.fold3.com/browse/273/); Pension records for Peter Churchwell, Henry Kettell, and William Page, RG 15, National Archives and Records Administration; Lucia C. Stanton, “Daniel Fossett Documentary References;” Cincinnati Daily Enquirer, January 5, 1866 and October 10, 1873, accessed at genealogybank.com; Frederick A. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion, vol. 3 (New York: T. Yoseloff, 1959); Earl J. Hess, Into the Crater: The Mine Attack At Petersburg, (Columbia, S.C: University of South Carolina Press, 2010); Wilson A. Greene, A Campaign of Giants: The Battle for Petersburg, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2018); Kelly D. Mezurek, For Their Own Cause: The 27th United States Colored Troops, (Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 2016); Donald R. Shaffer, After the Glory: The Struggles of Black Civil War Veterans, (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004); Richard, Slotkin, No Quarter: The Battle of the Crater, 1864, (New York: Random House, 2009); Lucia C. Stanton, "Those Who Labor for My Happiness": Slavery At Thomas Jefferson's Monticello, (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2012); Richard S. Slotkin, “The Battle of the Crater,” The Essential Civil War Curriculum, https://www.essentialcivilwarcurriculum.com/the-battle-of-the-crater.html, accessed October 15, 2018; “STEVENSON, Andrew, (1784 - 1857),” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=S000891, accessed on November 5, 2018.