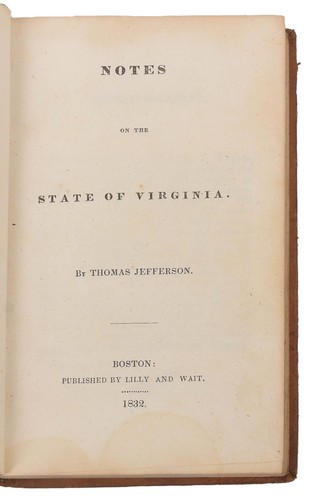

A compendium of information about the state and a commentary on natural history, society, politics, education, religion, slavery, liberty and law. It is a foundational text on racism; in Notes, Jefferson defines African Americans as inferior to whites.

See: https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/notes-on-the-state-of-virginia-1785

Entire document: https://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbcb.04902/?st=gallery

1784

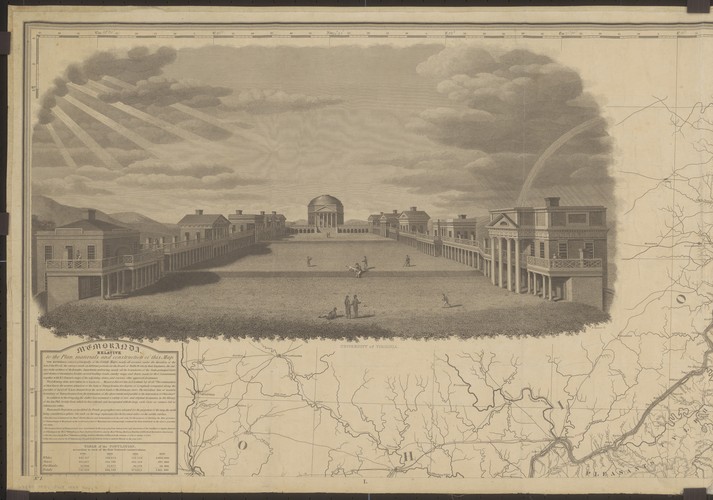

1827

University of Virginia Visual History Collection, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

A building where enslaved people worked and lived. It was constructed sometime between 1831 and 1856, and is only one of two such buildings that remains intact on Grounds.

Photo by Dan Addison of McGuffey Cottage

The Crackerbox was a kitchen with dwelling on the second floor where enslaved people worked and lived. It may date from 1826. It is only one of two such buildings that remains intact on Grounds.

Photo by Dan Addison of Crackerbox

In 1879, Mary Eliza Mahoney becomes the first trained African American nurse in the United States, graduating from the New England Hospital for Women and Children.

1879

Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons

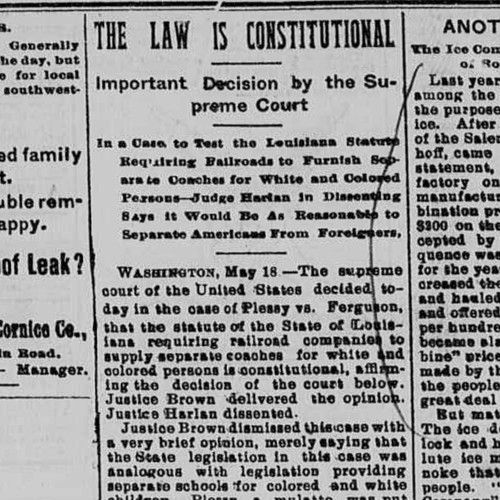

Jim Crow laws are upheld with the Supreme Court decision, Plessy v Ferguson, which legalizes segregation in public places by establishing the “separate but equal” ruling. This lasted for more than fifty years.

1896 - May 19th

The Roanoke Daily Times

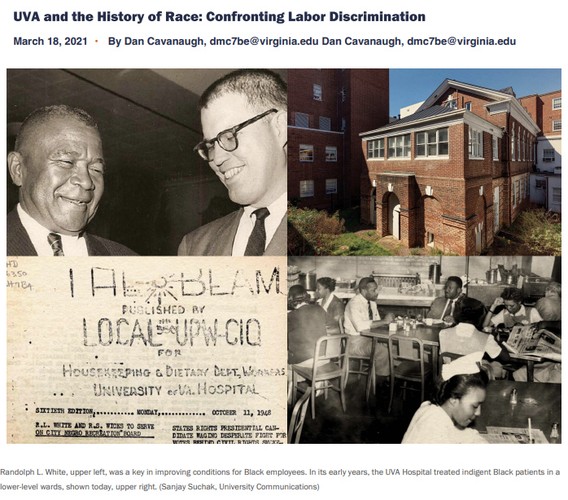

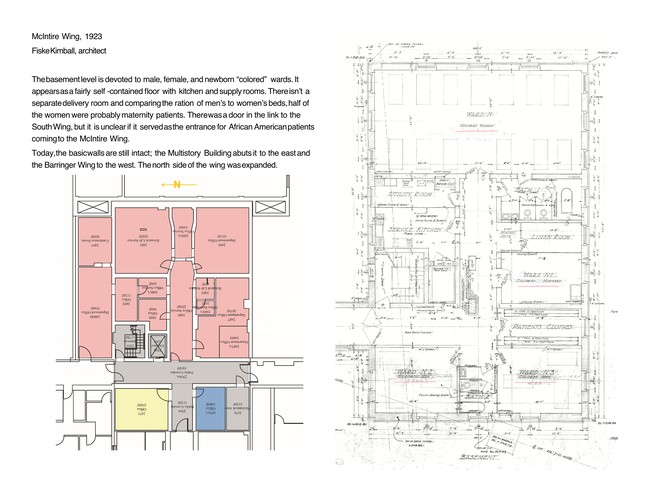

The first building of the University of Virginia Hospital opened on April 13, 1901. The designs for the 150-bed hospital were developed by the architect Paul J. Pelz. The hospital is under the direction of Dr. Paul Barringer, a leader of the eugenics movement and the hospital becomes an academic center of eugenics. To ensure adequate staffing of the hospital, the University of Virginia opened a trained school for nurses in the same year. Student nurses learned on the job working ten to twelve hours a day for two years before obtaining their degree. Both the hospital and the School of Nursing were established as segregated institutions. Until the 1960s, the hospital racially discriminated against African American patients and physicians, denying Black physicians hospital privileges and serving Black patients in segregated wards located in the hospital's basement level. Black women (and all men, regardless of race), were denied admission to the School of Nursing. Until the 1960s, the School of Nursing remains segregated with an all-white student body and faculty.

1901

Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia

In the 1890s, white nurses had organized two professional associations, what would become the National League for Nursing Education and the American Nurses Association. These organizations, however, discriminated against Black nurses. In the South, for example, state nursing associations excluded Black nurses from membership. In response, Black nurses organized their own professional nursing organizations, establishing the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NACGN)in 1908. The goals of this new organization were to achieve higher professional standards, to break down discriminatory practices facing black nurses, and to develop leadership among black nurses. Throughout the early- and mid-twentieth century, Black nurses and their leaders in the NACGN engaged in a "relentless" struggle to constantly push for recognition, and later, integration into the white body of American nursing.

1908

New York Public Library

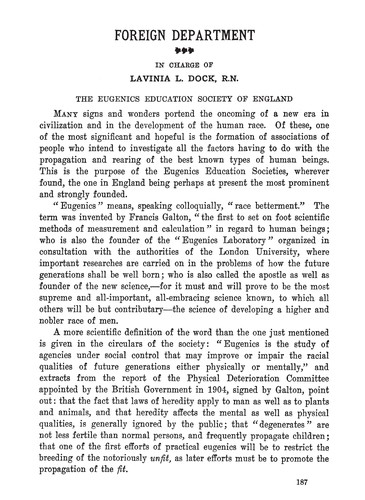

Eugenicists were interested in regulating prostitution, treating venereal disease, and taking measures to prevent inherited problems. Lavinia Dock was a nursing leader who graduated from New York's Bellevue Training School and was instrumental in enhancing nursing educational standards. She helped form the International Council of Nurses and wrote an early history of nursing with fellow nursing leader Adelaide Nutting. While endorsing eugenics as a movement, Dock's feminist ideals led her to resist regulation of prostitution by laws, however, and instead to call for education to promote changes in society that would prevent women from the necessity of prostitution.

1909

Until the 1960s, the hospital racially discriminated against African American patients and physicians, denying Black physicians hospital privileges and serving Black patients in segregated wards located in the hospital’s basement level.

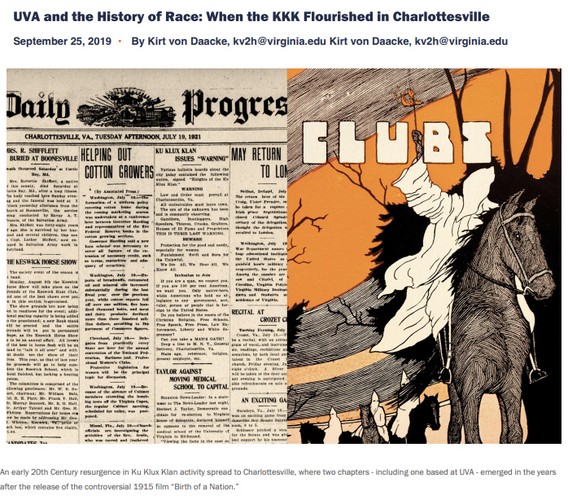

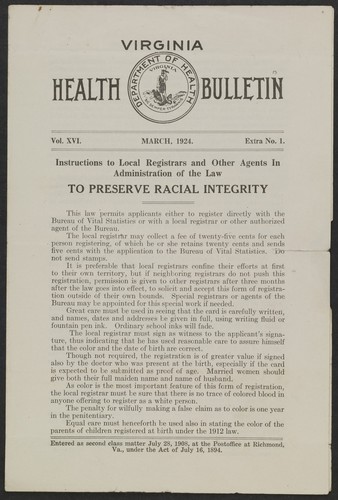

The sterilization act allowed for the legal sterilization of people deemed to have undesirable traits, this included people with epilepsy, mental illness, and cognitive disabilities. The Racial Integrity Act prohibited interracial marriage and defined as white a person “who has no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian.” These laws were shaped by the race science of eugenics.

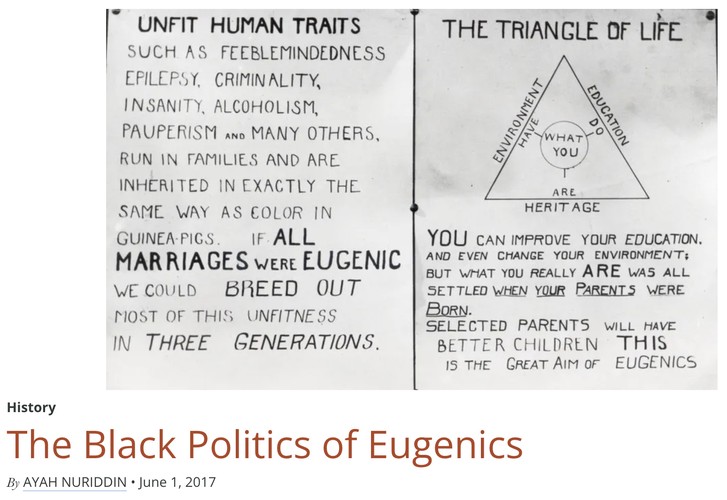

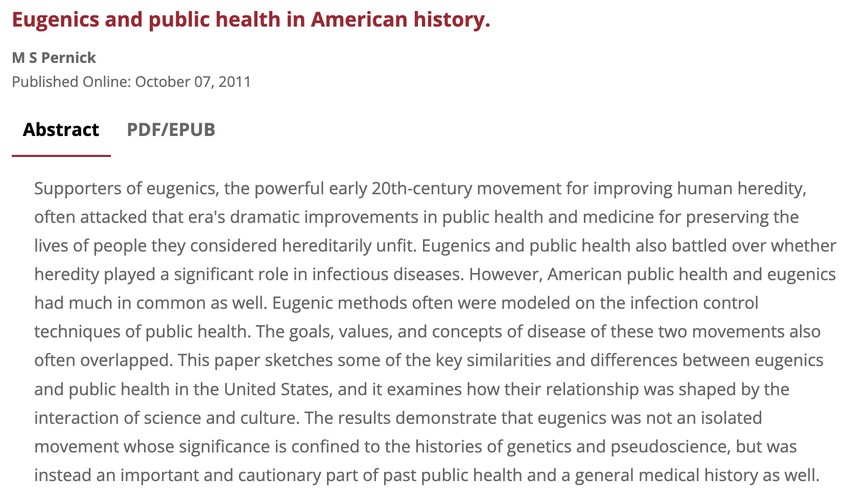

Eugenics, the study of the inheritance of physical, intellectual, and emotional characteristics, brought together many disciplines with the goal of advancing society and health. Eugenics became part of the program to combat venereal disease and other infections, thereby easily overlapping with public health measures. At the same time, these measures contributed to exclusionary policies that stigmatized certain groups. Termed “scientific racism,” these policies were part of overarching health campaigns that included a variety of people and groups – nurses, physicians, public health workers, eugenic societies, and governments.

Eugenics flourished at UVA under the leadership of President Edwin Alderman, who recruited several leaders of the eugenics movement to teach at UVA. These included Harvey Jordan, Robert Bean and Lawrence Royster in the medical school, and Ivey Lewis in biology. Nursing students at UVA learned about eugenics in their curricula, from UVA physicians (including Jordan), and the 1917 the National League for Nursing Education’s Standard Curriculum for Schools of Nursing. Its recommendation of guidelines for all basic nurse training programs included a course in eugenics. Eugenics profoundly affected social science, nursing, and public health in the early twentieth century. The legacy of eugenics in health care was prejudice and structural racism.

1934

University of Virginia Special Collections

Second row: William Hall Goodwin (3rd from left), Edwin A. Alderman (University President) (7th from left), Josephine McLeod (8th from left), James Carroll Flippin (8th from right), J. Edwin Wood (3rd from right), Lawrence T. Royster (far right). Third row: William E. Bray (far left), Harvey E. Jordan (3rd from left), Edwin P. Lehman (6th from left), Henry B. Mulholland (9th from right), Halsted Hedges (2nd from right). Fourth row: Dudley C. Smith (8th from left), John H. Neff (7th from right), Vincent W. Archer (2nd from right), Robert B. Bean (far right).

Graduation class of 1930. This photograph is significant because it is typical of most nursing programs that feature their graduating classes in full uniform. The specific UVA nursing uniform became an honorable distinction for graduates. The photograph also shows the segregated nature of nursing schools with an all-white student body and faculty. The men in the photograph are all UVA faculty members (such as Harvey Jordan) who either are on the advisory board of the School of Nursing (link to 1939 Plan of Instruction) or who are lecturers to nursing students. As faculty leaders, these men became experts in eugenics and led the University of Virginia to become a center of eugenics teaching.

Eugenics, the study of the inheritance of physical, intellectual, and emotional characteristics, brought together many disciplines with the goal of advancing society and health. Eugenics became part of the program to combat venereal disease and other infections, thereby easily overlapping with public health measures. At the same time, these measures contributed to exclusionary policies that stigmatized certain groups. Termed "scientific racism," these polices were part of overarching health campaigns that included a variety of people and groups – nurses, physicians, public health workers, eugenic societies, and governments. Reformers, including nurses, argued for eugenic improvement while also enhancing environmental changes. Significantly, public health and nursing's role in it came of age when biological approaches to social problems were near their height. The legacy of eugenics in health care was prejudice and structural racism.

1930

Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia

In 1937, the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NACGN) held their Northeastern Regional Conference at St. Philips School of Nursing in Richmond, VA. This newspaper account provides details about the conference. NACGN conferences were important venues where Black nurses discuss issues of professional concern and enhance their work to eliminate segregation in nursing. The St. Philip School of Nursing was established in 1920 in Richmond; was associated with St. Philip Hospital, a Black hospital. The school offered two nursing programs: a diploma program and, eventually, course work that led to a baccalaureate degree within the Medical College of Virginia (MCV).

1937 - March 31st

Take Special Train to Nurses Convo, New York Amsterdam News, (Apr 3, 1937), 3

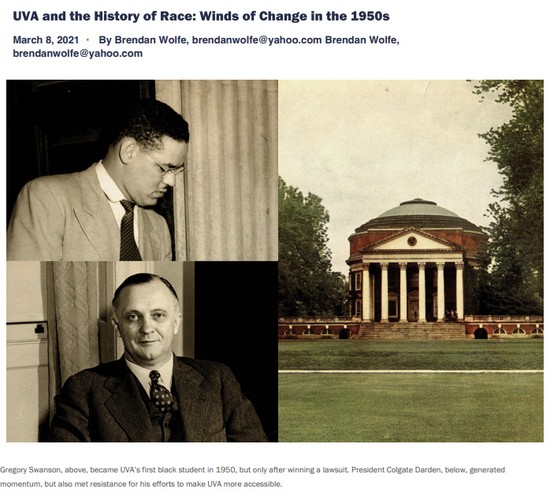

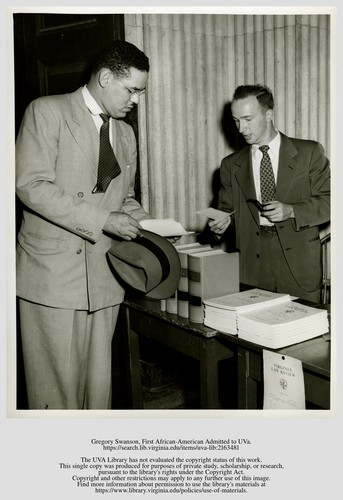

First African American student, Gregory Swanson, is admitted to the University of Virginia's Law School after the U.S. Supreme Court passes Sweatt v Painter, which banned racial segregation in professional and graduate schools. That law, however, did not apply to undergraduate or K-12 schools.

1950

UVA Visual History Collection

Charlottesville Tribune article by TJ Sellers describing the unequal conditions of the Black public wards at UVA Hospital, noting that Black patients are still required to pay the same rates as white patients. Sellers writes that any Charlottesville resident could "walk through the various wards of the University Hospital and note the glaring differences in the physical condition" of the Black and white public and private wards. He also explains that Black patients do not "receive the same professional courtesy accorded to white patients," with hospital staff addressing Black patients only by their first names, rather than using the "courtesy title" used for white patients.

1951 - May 26th

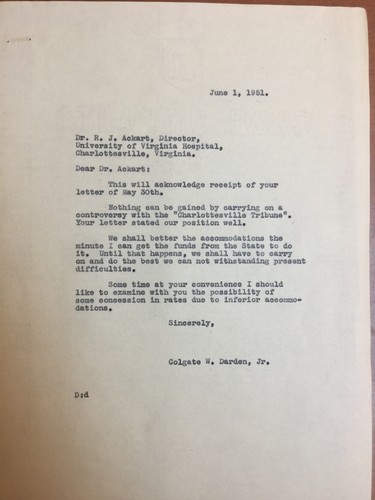

Letter from UVA President Colgate Darden to R. J. Ackart, Director of UVA Hospital acknowledging that Black patients were given "inferior accommodations" at UVA Hospital. Darden refers to a recent series of articles in the Charlottesville Tribune by T.J. Sellers that criticized the hospital for its discriminatory treatment of Black patients.

1951 - June 1st

Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia

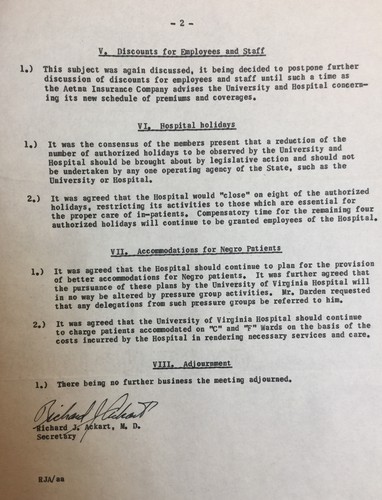

Hospital leadership agrees to plan for better accommodations for Black patients and affirm that they will not be swayed by "pressure groups."

1951 - June 12th

Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia

UVA Hospital director, R.J. Ackart reports discussion with civil rights leaders and proposes new policy requiring courtesy titles for Black patients. Dr. Ackart suggested that a formal policy in this regard be promulgated by memorandum from the Director's Office. After discussion it was decided that, because of difficulties in policing and enforcing such a policy a directive should not be issued. Also included are the related hospital policy documents.

June 1, 1951 to December 11, 1951

Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia

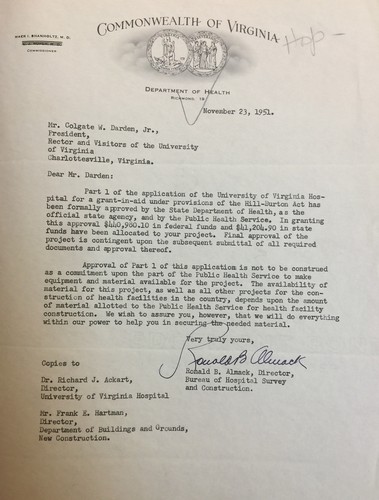

Letter from Ronald B. Almack, director of the Bureau of Hospital Survey and Construction, Dept. of Health, Commonwealth of Virginia to Colgate W. Darden, President of UVA, dated November 23, 1951, reporting that Part 1 UVA Hospital's application for Hill-Burton funds has been approved. The Hill-Burton Act of 1946 gave hospitals, nursing homes, and other health care facilities federal grants to construct new hospitals and to modernize existing ones, in return for the promise of provision of health services to communities regardless of ability to pay. The act did not, however, mandate desegregation of hospitals and other health care facilities as a prerequisite for obtaining federal funding. Thus, federal money was used to build racially-exclusive hospitals. Even though the Hill-Burton Act provided federal funding to some white hospitals such as UVA to expand segregated wards to African Americans, many of these wards were in basements with separate entry areas for African Americans. Thus, while access to white hospitals was expanded to African Americans, this did not mean equal treatment.

November 23, 1951

Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia

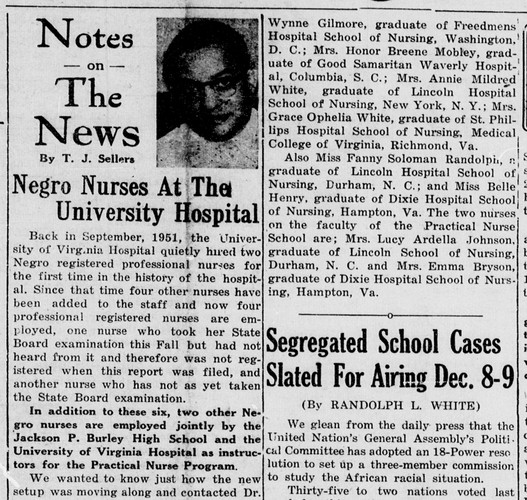

Charlottesville Tribune article by T.J. Sellers describing UVA Hospital's hiring of its first Black registered nurses in September 1951, followed by four more Black nurses the following year. The article names the nurses who were hired as Weda Gilmore, Honor Mobley, Annie White, Grace White, Fanny Randolph, and Belle Henry. And the article explains that the Black nurses received the same salary and other privileges that the white nurses receive. The article also explains that UVA Hospital hired two Black licensed practical nurses, Lucy Johnson and Emma Bryson.

1952-12-06

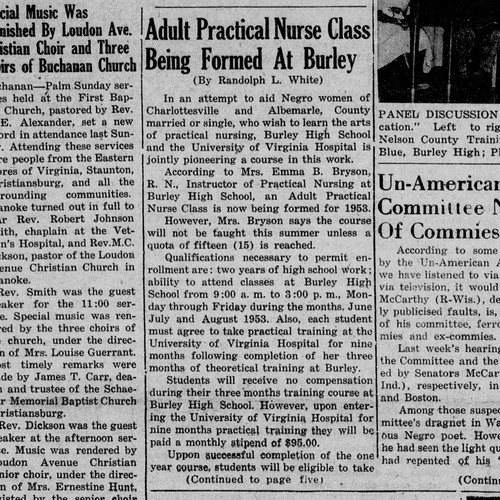

Newspaper article announcing the establishment, in 1952, of the Jackson P. Burley High School Licensed Practical Nurses Program, in collaboration with the University of Virginia Hospital. Although Black women were racially excluded from the UVA School of Nursing, this new LPN program was open to Black women, who completed their studies at Jackson P. Burley School and practiced at the University of Virginia Hospital. Because of the segregationist and exclusionary practices in nursing education and health care, Black women who wanted to pursue careers in nursing in the early 1950s had, in general, three options available to them: apply to a licensed practice nursing program, a historically Black professional nursing program, or apply to a nursing school that accepted Black students under the restriction of quotas. The Burley-UVA Hospital LPN program was thus an important way for Black women in Charlottesville and Albemarle County to enter the field of nursing.

1953 - April 4th

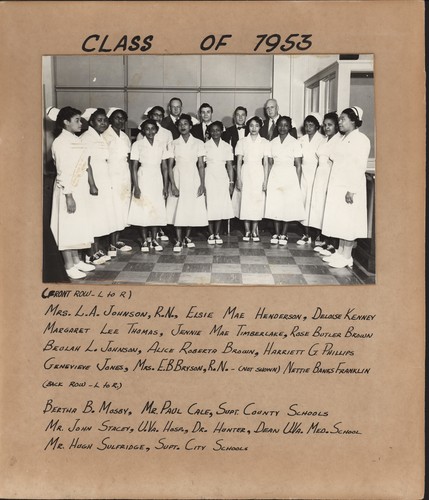

Graduation photograph of the class of 1953; the first class to graduate from the Jackson P. Burley High School-University of Virginia Hospital Licensed Practical Nursing Program. The photograph also includes the superintendents of the city and county schools, the UVA Hospital director, and the dean of UVA medical school.

1953

Historical Collections, Bjoring Center for Nursing Historical Inquiry, University of Virginia

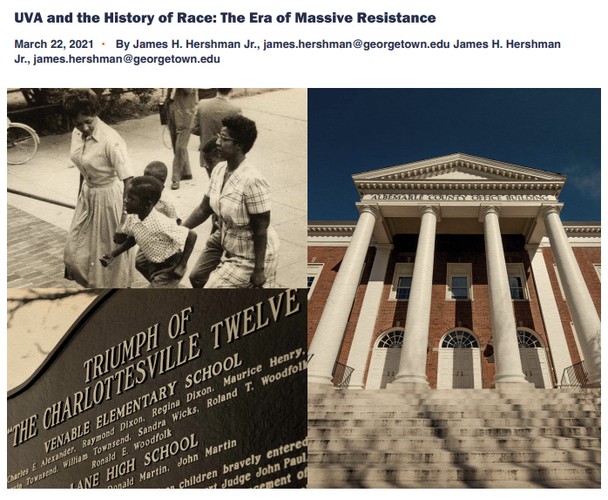

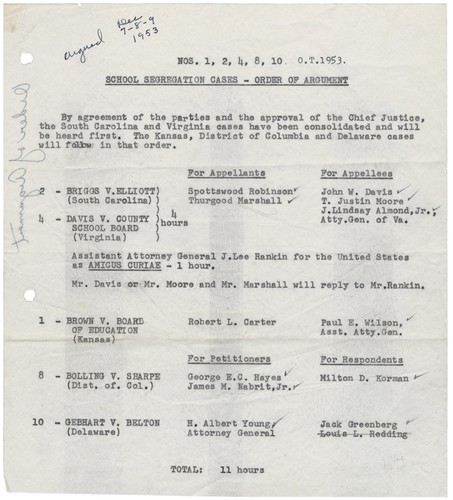

Supreme Court decision, Brown v Board of Education, bans racial segregation in public schools, affirming that separate but equal schools are not, in fact, equal. Virginia is connected because it was one of five legal cases (e.g., Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia) involved in the decision. Include in narrative discussion (not as separate entries) the following:

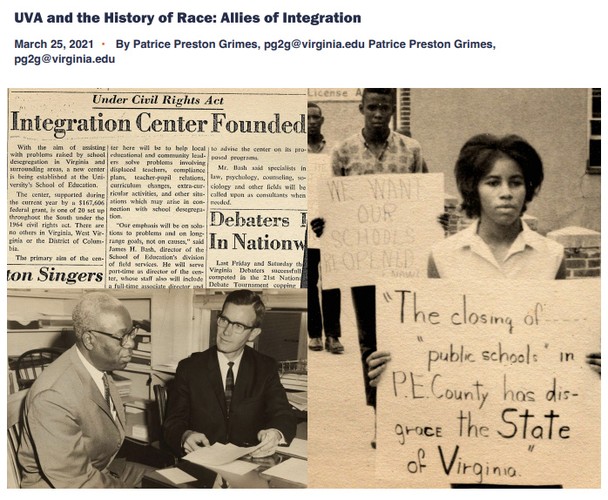

In response to the Brown decision, Senator Harry F. Byrd, Jr., and other Virginia lawmakers promote the “Southern Manifesto,” which opposes school integration. 1955 – Brown II. Supreme Court rules that school desegregation must take place with "all deliberate speed.”

1956 – To protest the Brown decision, Senator Byrd and other southern lawmakers call upon the state to carry out acts of “massive resistance.”

1958 – Governor J. Lindsay Almond closes schools in Charlottesville, Norfolk, and Alexandria. Black students are severely affected, while many White students get access to private White-only facilities. Because Albemarle Training School and Jefferson School in Charlottesville were segregated schools for African American students, however, they did not close.

1959 – Virginia Supreme Court overturns school closings.

The Brown decision set a precedent, which led civil rights activists to legally target segregated hospitals. They first aimed at the Veterans Administration, and in 1954 it officially ended segregation in its hospitals. This was significant in many ways. Through the Veterans Administration hospitals, for example, many Black nurses such as UVA graduate Mavis Claytor had greater opportunities to work in desegregated facilities.

Black activists were then successful in desegregating hospitals via the landmark 1962 Supreme Court ruling, Simkins v Cone, which mandated that private hospitals receiving federal funding under the Hill-Burton Act could not discriminate based on race, as protected by the Equal Protection clause of the 14th Amendment. Simkins v Cone also outlawed sections in the original Hill-Burton Act that provided for separate-but-equal hospital access and services. Although African American nurses had been employed in some white hospitals, until Simkins, almost no hospitals permitted African American physicians to obtain staff privileges.

1654

University of Virginia Law Library

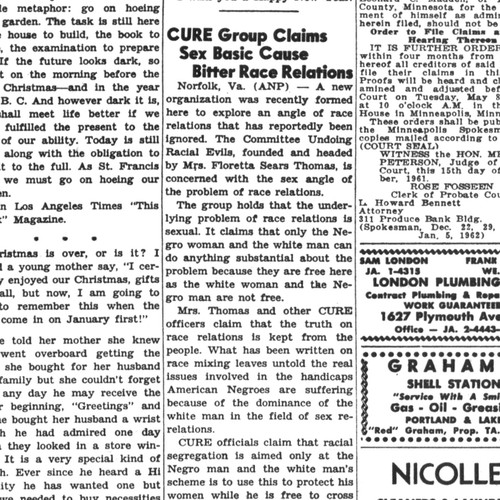

Newspaper article describing the establishment of a new civil rights group in Norfolk, VA. The Committee Undoing Racial Evils (CURE), was founded and led by Floretta Sears Thomas, a Black nurse. CURE was founded to address what the group sees as "the underlying problem of race relations," sex relations and particularly, "the dominance of the white man in the field of sex relations." According to Sears, this issue was not being addressed by any other civil rights organization.

1961 - December 29th

After the NAACP and the National Medical Association pushed for hospital integration, arguing that segregated hospitals led to inferior care for Black Americans, most Black hospitals closed. In 1962, St. Philip’s School of Nursing closed, reflecting the widespread closing of Black hospitals.

circa 1962

Special Collections and Archives, Virginia Commonwealth University

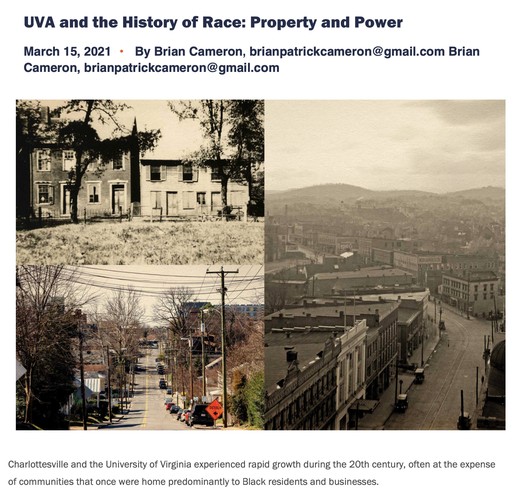

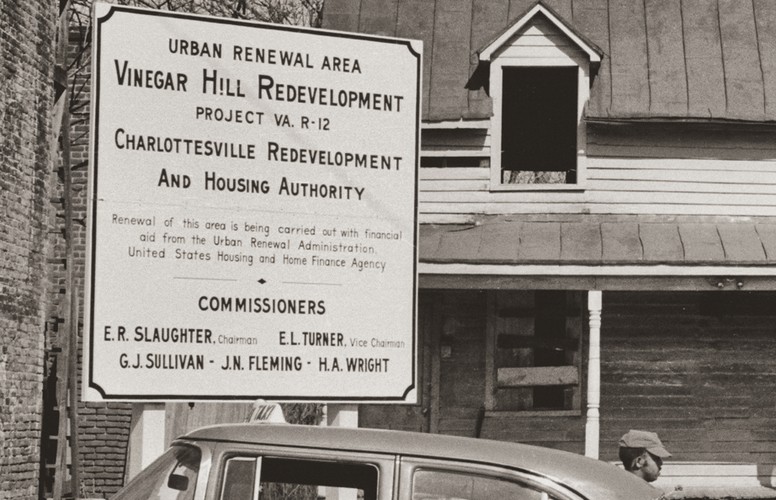

Through the early 1960s, the Charlottesville neighborhood of Vinegar Hill was a center of Black property ownership, business, and culture for African American residents that had been built by formerly enslaved men and men. However, in 1960, the Charlottesville Redevelopment and Housing Authority authorized the redevelopment of Vinegar Hill, with the support of federal urban renewal funds, destroying this important community.

c. 1964

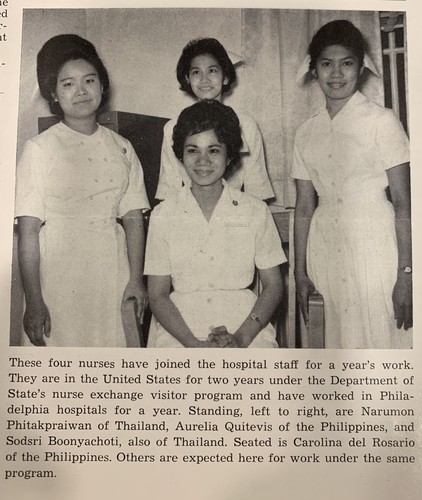

Two stories and photographs from UVA Hospital's Draw Sheet about internationally educated nurses from the Philippines and Thailand who work at UVA Hospital. The nurses work at the hospital under the auspices of the U.S. State Department's Exchange Visitor Program (EVP). Congress established the EVP in 1948. Participants of the EVP came to the U.S. for up to two years to work and study in sponsoring institutions, which provided them with a monthly stipend. The ANA and individual hospitals, including UVA Hospital and other Virginia hospitals, were among the several thousand sponsoring U.S. agencies and institutions. By the late 1960s, Filipino nurses constituted the overwhelming majority of internationally-educated nurses who entered the U.S.

1964 to 1967

Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia

Passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 prohibited segregation in public accommodations and racial discrimination in employment. This was the beginning of the end of racial segregation in hospitals that received federal funding.

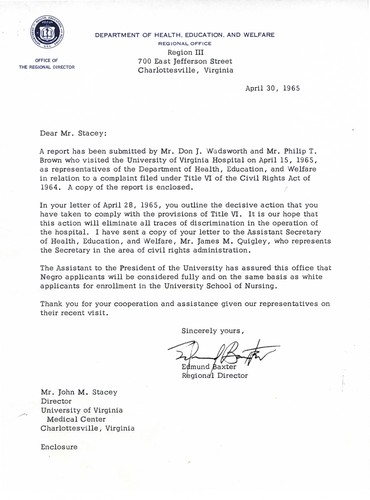

On April 30, 1965, the NAACP filed a complaint with the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare to investigate violations of the Civil Rights Act and discrimination by the University of Virginia Hospital.

1965 - April 3rd

Historical Collections, Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia

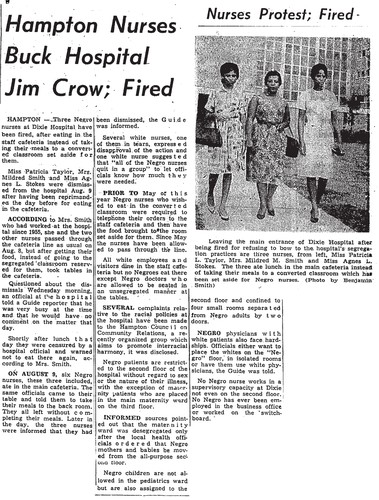

1966 - May 7th

ProQuest Historical Newspapers [Source: “Hampton Nurses Buck Hospital Jim Crow; Fired,” Norfolk Journal and Guide (Aug 24, 1963), p. 15.; “Hampton Hospital Told to Hire 3 Nurses Again,” Norfolk Journal and Guide (May 7, 1966), p. 1].

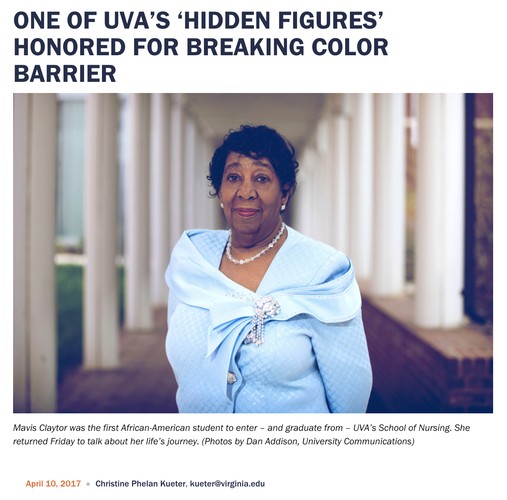

Mavis Claytor was the first Black woman to graduate from the University of Virginia School of Nursing, earning her BSN in 1970. Claytor entered the BSN program in 1968, after graduating first from the Lucy Addison High School of Practical Nursing in Roanoke in 1963, and the Helene Fuld Provident Hospital's Registered Nursing Program in Baltimore in 1967. After earning her BSN, Claytor returned to the historically Black Burrell Memorial Hospital in Roanoke, where she worked as an RN on the general medical-surgical floor. She also worked as a public health nurse, and in 1976, joined the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Salem, Virginia, where she worked as a mental health nurse. In 1983, Claytor returned to the UVA School of Nursing to complete a master's program in mental health, earning her MSN in 1985. Claytor continued working at Salem's Veterans Affairs Medical Center, retiring after 30 years of service. On April 7, 2017, School of Nursing Dean Dorrie Fontaine offered a formal apology to Claytor, acknowledging the discriminatory practices that excluded Black students from attending or fully engaging in University enrollment, matriculation, traditions, and student activities.

1970

Private collection of Mavis Claytor

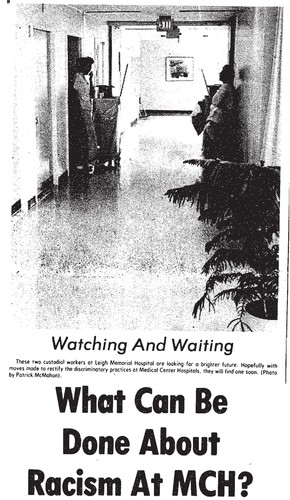

News article describing the ongoing problem of racial discrimination at Medical Center Hospitals (MCH) in Norfolk, VA, where there are "widespread patterns of discrimination in hiring into certain departments, in promotions, in disciplinary actions, and in the area of corporate control, responsibility, and power." The article describes options available to employees who experience discrimination, which includes filing a lawsuit. President of the Norfolk chapter of the NAACP is quoted as saying "We'd be happy to talk to anyone at MCH who feels they've been discriminated against." The article describes "One promising development at MCH" to confront the problem of discrimination, and that are an effort led by registered nurses to organize a union at MCH: "Besides the obvious advantages of higher wages, better benefits, job security, and a real grievance procedure," a union contract could "help employees fight against discrimination at MCH." The drive had already succeeded in "involving growing numbers of MCH employees: men and women, black, white, and Filipino."

1979

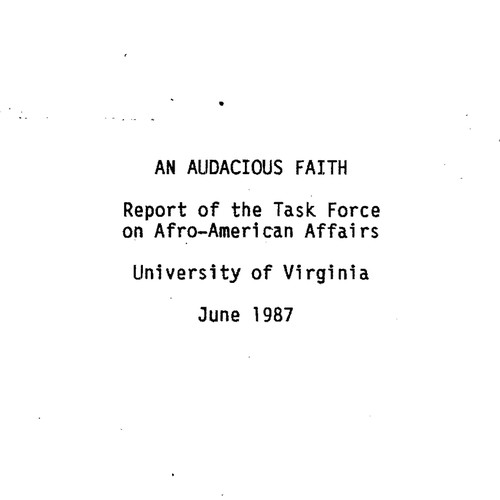

Report of task force established by University president Robert O'Neil to investigate the state of race relations on UVA Grounds. The report examined the past, present, and future of race relations at UVA. It found that while some progress had been made in terms of race relations, the "self-transformation of the University of Virginia into a genuinely integrated institution equally receptive to people of all races is far from complete.

1987 - July

https://voicesforequity.virginiaequitycenter.org/assets/documents/1987%20an-audacious-faith.pdf

Report by the Office of Equal Opportunity Programs, "An Examination of the University's Minority Classified Staff (The Muddy Floor Report)," published in June 1996. The report highlighted "glaring disparities" in employment opportunities, performance evaluations, and disciplinary sanctions between white and Black employees.

It found that African Americans were overrepresented in unskilled positions in the University, and virtually nonexistent in high-salaried, managerial positions.

1996 - June

https://www.nursing.virginia.edu/diversity/

IDEA (Inclusion, Diversity, Excellence, Achievement) is initiated at UVA School of Nursing. The overarching goal of IDEA is to improve respect, inclusion, and engagement in the school’s community of students, staff, and faculty.

2015

https://www.nursing.virginia.edu/diversity/

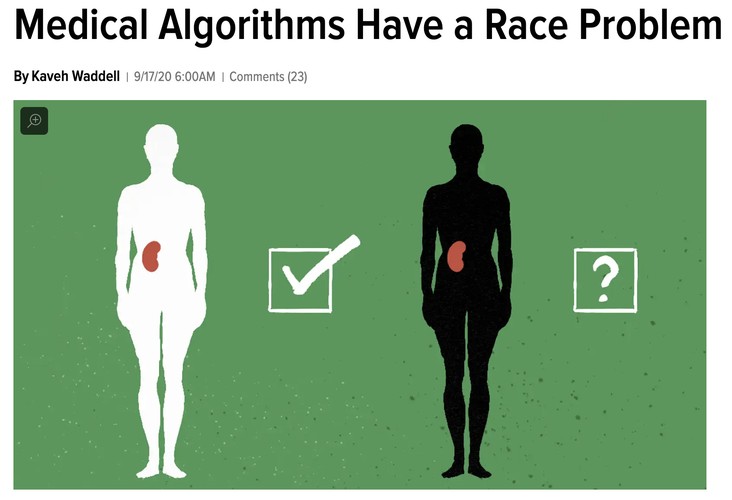

Black Americans are systematically underrated for pain relative to white Americans. This article reports on the results of a study conducted at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, which examined whether racial bias in pain assessment and treatment is related to false beliefs about biological differences between Blacks and whites.

The findings suggest that individuals with at least some medical training hold and may use false beliefs about biological differences between Blacks and whites to inform medical judgments, which may contribute to racial disparities in pain assessment and treatment.

2016 - April 19th

PNAS

The Charlottesville City Council creates the Blue-Ribbon Commission on Race, Memorials, and Public Spaces.

In 2017, the Charlottesville City Council votes to remove the Robert E. Lee statue and rename Lee Park to Emancipation Park.

2011 - July 27th

Photograph taken by Billy Hathorn, Wikimedia Commons

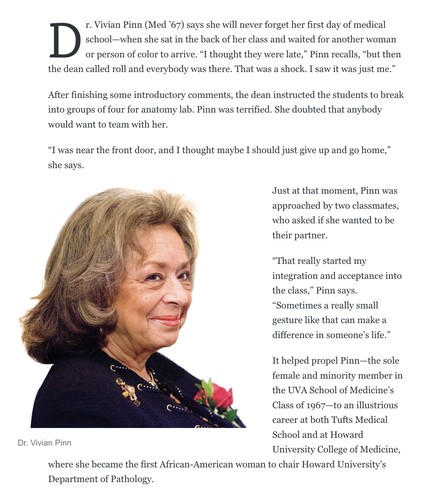

Jordan Hall is renamed Pinn Hall, for Dr. Vivian Pinn (Med ‘67), the only woman and only African American student in her class at the UVA School of Medicine.

2016

After Donald Trump elected President of the U.S., there is an uptick in racist acts in the UVA Hospital from patients and their families. This precipitated the establishment of “Stepping In” training, in which the School of Nursing is involved(for example, nursing students testifying about their experiences in the hospital).

All 3rd and 4th year BSN students, BSN faculty and clinical instructors, and CNL students, participate in the training, Stepping In: Responding to Disrespectful and Biased Behavior in Health Care.

2017 - April 26th

Unite the Right protesters, led by UVA alumni, march on the Grounds of the University of Virginia in protest of the city’s plan to remove the Lee statue. One white supremacist drives his car into a group of counter protesters that results in the death of Heather Heyer. Two others perish as well: police officers Trooper-Pilot Berke M. Bates and Pilot Lt. H. Jay Cullen, who die from a helicopter crash as they covered the incident.

Nurses working in triage tents and in local emergency departments take care of people injured during the protests.

2017 - August 12th

https://www.cnn.com/2017/08/12/us/white-nationalists-tiki-torch-march-trnd/index.html

2017 - August 20th

Opinion/Commentary by Allison McDowell in the Daily Progress

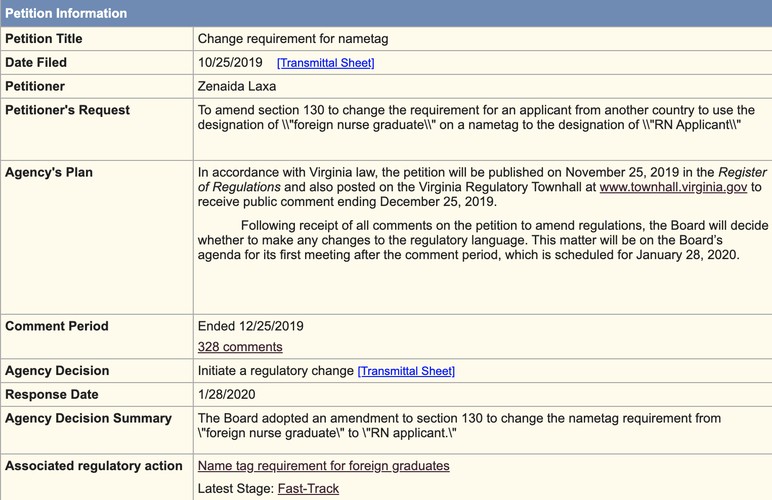

The activism of Filipino nurses in Virginia leads to the overturning Virginia Board of Nursing law, which had required internationally educated nurses to list “foreign graduate nurse” on their hospital name tags. This designation is replaced with “RN Applicant.”

2019 - October 25th

Virginia Board of Nursing

The murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer on May 25, 2020, prompted a reckoning at the UVA School of Nursing, making clear that the School of Nursing were not making the deep substantive changes necessary to truly become an antiracist school. During summer 2020, an Antiracism Working Group comprised of students, faculty and staff in the School of Nursing mobilized and met weekly throughout the summer and into the fall to develop further concrete actions to address racism and other bias in the hospital. The goal of this student-led group aimed to prepare students and faculty to address racism and other forms of bias, as a target of, witness to, or perpetrator of this behavior in clinical settings. The group felt it to be essential for nursing students and other stakeholders to have a background understanding of the history of race and racism in our local context before engaging in clinical practice.

2020 - October 2nd

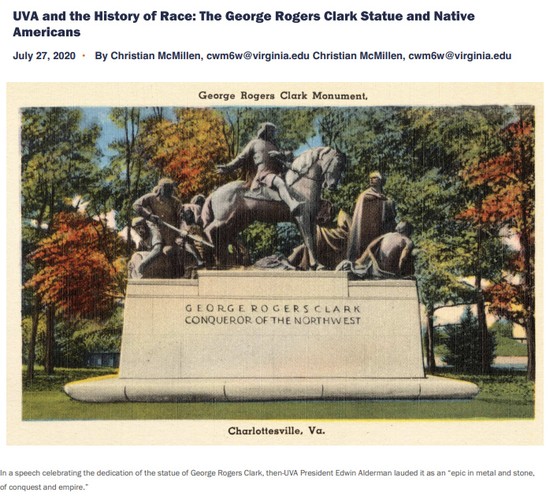

Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and George Rogers Clark statues in Charlottesville come down.

2021 - July 21st

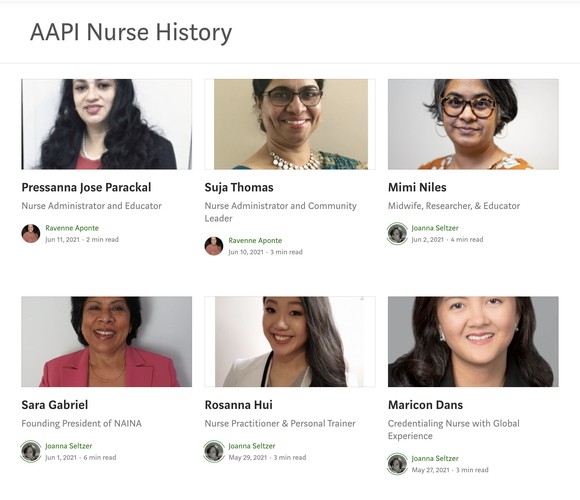

“AAPI Nurse History,” Nurses You Should Know, retrieved from https://medium.com/nurses-you-should-know/aapinursehistory/home.

2007

Warwick Anderson, “Immunization and Hygiene in the Colonial Philippines,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 62, no. 1 (2007): 1-20, doi: 10.1093/jhmas/jrl014.

2008

Warwick Anderson, “Indigenous Health in a Global Frame: From Community Development to Human Rights,” Health History 10, no. 2 (2008): 94-108, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40111305.

2017

Zinzi D. Bailey, Nancy Kreiger, Madina Agenor, Jasmine Graves, Natalia Linos, and Mary T. Bassett, “Structural Racism and Health Inequities in the USA: Evidence and Interventions,” Lancet 389, no. 10077 (2017): 1453-146, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X.

“Black Nurse History,” Nurses You Should Know, retrieved from https://medium.com/nurses-you-should-know/blacknursehistory/home.

2007

Lundy Braun, Anne Fausto-Sterling, Duana Fullwiley, Evelynn M. Hammonds, Alondra Nelson, William Quivers, Susan M. Reverby, and Alexadra E. Shields, “Racial Categories in Medical Practice: How Useful are They?” PLos Medicine 4, no. 9 (2007): 1423-1428, doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040271.

2020

Merlin Chowkwanyun and Adolph L. Reed, “Racial Disparities and Covid-19 – Caution and Context, New England Journal of Medicine 383, no. 3 (2020): 202-203, doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2012910.

2020

Catherine Ceniza Choy, “Nursing Justice: Filipino Immigrant Nurse Activism in the United States,” Nursing Clio (2020), https://nursingclio.org/2020/12/03/nursing-justice-filipino-immigrant-nurse-activism-in-the-united-states/.

2010

Catherine Ceniza Choy, “Nurses Across Borders: Foregrounding International Migration in Nursing History,” Nursing History Review 18 (2010): 12-28, doi: 10.1891/1062-8061.18.12.

2020

Leonard W. D’Avolio, “Beyond Racial Bias: Rethinking Risk Stratification in Health Care,” Health Affairs (2020), doi: 10.1377/hblog20200109.382726.

2000

Gregory Michael Dorr, "America's Place in the Sun: Ivey Forman Lewis and the Teaching of Eugenics at the University of Virginia, 1915-1953." Journal of Southern History, Vol. 66, No. 2 (2000): 257-296.

2010

Laurie Meijer Drees, “Indian Hospitals and Aboriginal Nurses: Canada and Alaska,” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History 27, no. 1 (2010): 139-161, doi: 10.3138/cbmh.27.1.139.

2021

E. Thomas Ewing, Kiana Wilkerson, and Katherine Randall, “Our Work is Not Complete Yet: The Tuberculosis Nurse Training Program at Virginia’s Piedmont Sanatorium,” Nursing Clio (2021), https://nursingclio.org/2021/12/02/our-work-is-not-complete-yet-the-tuberculosis-nurse-training-program-at-virginias-piedmont-sanatorium/.

2007

Angela Gonzalez, Judy Kertesz, and Gabrielle Tayac, "Eugenics as Indian Removal: Sociohistorical Processes and the De(con)struction of American Indians in the Southeast." Public Historian, Vol. 29, No. 3 (2007): 53-67.

2020

Rachel R. Hardeman, Eduardo M. Medina, and Rhea W. Boyd, “Stolen Breaths,” New England Journal of Medicine 383, no. 3 (2020): 197-199, doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2021072.

2003

Darlene Clark Hine, “Black Professionals and Race Consciousness: Origins of the Civil Rights Movement, 1890-1950,” Journal of American History 89, no. 4 (2003): 1279-1294, doi: 10.2307/3092543.

1982

Darlene Clark Hine, “The Ethel Johns Report: Black Women in the Nursing Profession, 1925,” The Journal of Negro History 67, no. 3 (1982): 212-228, doi: 10.2307/2717387.

2021

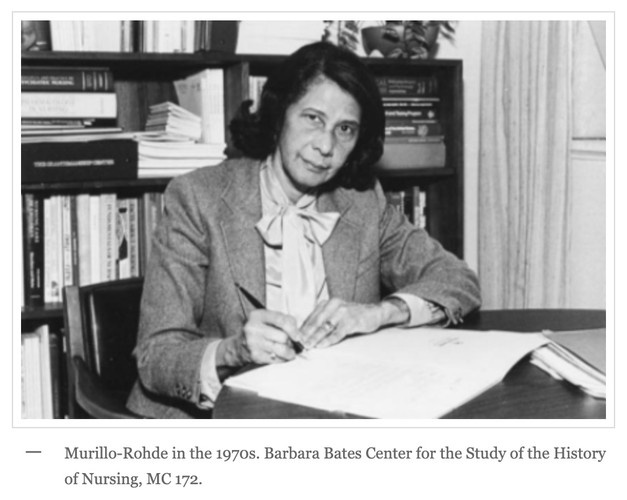

Logan Heiman, “Celebrating National Hispanic Heritage Month: Dr. Ildaura Murillo-Rohde, PhD, RN, FAAN,” (2021), retrieved from https://nyamcenterforhistory.org/tag/hispanic-nurses/.

“Hispanic Nurse History,” Nurses You Should Know, retrieved from https://medium.com/nurses-you-should-know/hispanicnursehistory/home.

2019

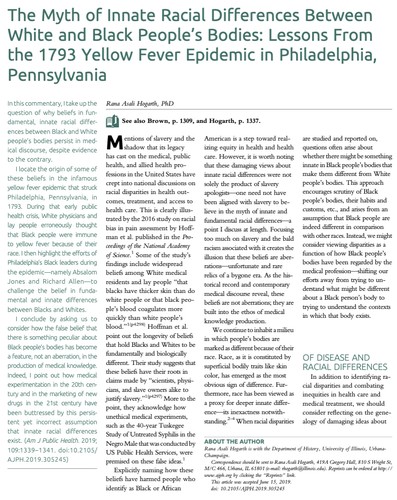

Rana Hogarth, “The Myth of Innate Racial Differences Between White and Black People’s Bodies: Lessons From the 1793 Yellow Fever Epidemic in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,” American Journal of Public Health 109 (2019): 1339–1341, doi:10.2105/AJPH.2019.305245.

2019

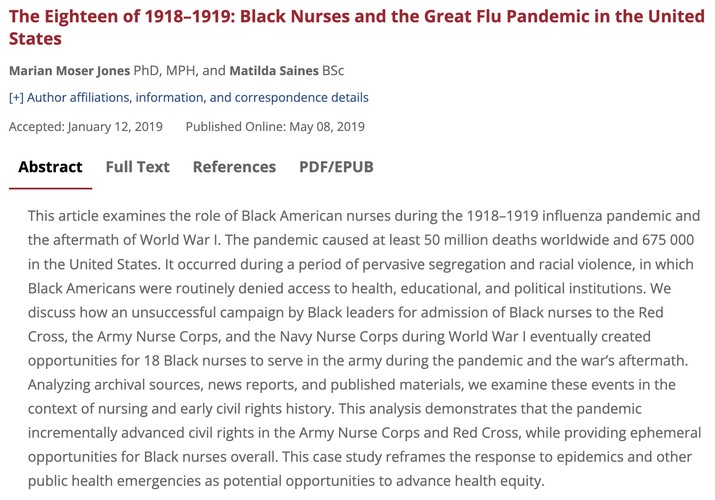

Marian Moser Jones and Matilda Saines, “The Eighteen of 1918-1919: Black Nurses and the Great Flu Pandemic in the United States,” American Journal of Public Health 109, no. 6 (2019): 877-884, doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305003.

2017

Stephanie Jones-Rogers, “‘[S]he Could...Spare One Ample Breast for the Profit of Her owner’: White Mothers and Enslaved Wet Nurses’ Invisible Labor in American Slave Markets,” Slavery & Abolition: A Journal of Slave and Post-Slave Studies 38, no. 2 (2017): 337-355, doi: 10.1080/0144039X.2017.1317014.

Winter 2023

Christine Kueter, "Black, Latinx Leaders to Nursing Students: 'You Belong Here.'" Virginia Nursing Legacy Magazine, Winter 2023. https://magazine.nursing.virginia.edu/flipbooks/vnl-magazine-2023-winter/lnsu-bsna-groups/

2022

Christine Kueter, "NoTranslation Necessary: Meet the Founders of the Latinx Nursing Student Union," UVA SON News (November 10, 2022), https://www.nursing.virginia.edu/news/latinx-student-group/

2021

Christine Phelan Kueter, “‘Doing This Out Loud’: Nursing Students Mix Activism, Action and Learning,” UVA Today (April 9, 2021), https://news.virginia.edu/content/doing-out-loud-nursing-students-mix-activism-action-and-learning.

2019

Christine Phelan Kueter, “New Exhibit Uncovers the History of Filipino Nurses in Virginia,” UVA Today (July 2, 2019), https://news.virginia.edu/content/new-exhibit-uncovers-history-filipino-nurses-virginia.

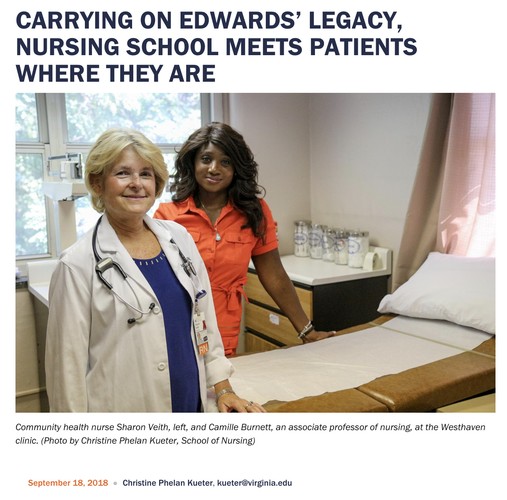

2018

Christine Phelan Kueter, “Carrying on Edwards’ Legacy, Nursing School Meets Patients Where They Are,” UVA Today (September 18, 2018), https://news.virginia.edu/content/carrying-edwards-legacy-nursing-school-meets-patients-where-they-are.

2017

Christine Phelan Kueter, “One of UVA’s ‘Hidden Figures’ Honored for Breaking Color Barrier,” UVA Today (April 10, 2017), https://news.virginia.edu/content/one-uvas-hidden-figures-honored-breaking-color-barrier.

2017

Rosie J. Knight, “African Americans, Slavery, and Nursing in the US South,” Nursing Clio, (2017), https://nursingclio.org/2021/01/07/african-americans-slavery-and-nursing-in-the-us-south/.

1992

Stephen Labaton, “Benefits are Refused More Often to Disabled Blacks, Study Finds,” New York Times (May 11, 1992), https://www.nytimes.com/1992/05/11/us/benefits-are-refused-more-often-to-disabled-blacks-study-finds.html.

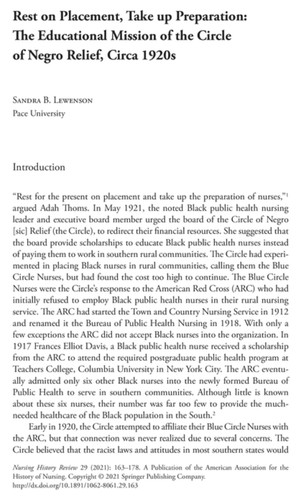

2020

Sandra B. Lewenson, “Rest on Placement, Take up Preparation: The Educational Mission of the Circle of Negro Relief, Circa 1920s,” Nursing History Review 29 (2020): 163-178, doi: 10.1891/1062-8061.29.163.

2019

Sandra B. Lewenson, “Hidden & Forgotten: Being Black in the American Red Cross Town & Country Nursing Service, 1912-1948,” Nursing History Review 27 (2019): 15-28, doi: 10.1891/1062-8061.27.15.

2020

Sandra B. Lewenson and Ashley Graham-Perel, “‘You Don’t Have Any Business Being This Good’: An Oral History Interview with Bernardine Lacey,” American Journal of Nursing 120, No. 8 (August 2020): 40-47, doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000694564.56696.ad.

2021

John P. A. Loannidis, Neil R. Powe, and Clyde Yancy, “Recalibrating the Use of Race in Medical Research,” Journal of the American Medical Association 325, no. 7 (2021): 623-624, doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.0003.

2021

Paul A. Lombardo and Gregory M. Dorr, “Eugenics, Medical Education, and the Public Health Service: Another Perspective on the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 80, no. 2 (2006): 291-316, doi: 10.1353/bhm.2006.0066.

2017

Mary Jane Logan McCallum, “The How and Why of Indigenous Nurse History,” Nursing Clio (2017), https://nursingclio.org/2017/11/30/the-how-and-why-of-indigenous-nurse-history.

2011

Natalia Molina, “Borders, Laborers, and Racialized Medicalization Mexican Immigration and US Public Health Practices in the 20th Century, American Journal of Public Health 101 (2011): 1024-1031, doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300056.

2021

Sabrina Moreno, “Asian American Virginians Continue to Face Barriers in Accessing Vaccines. Here’s What Advocates Say Would Help,” Richmond Times Dispatch (March 24, 2021), https://richmond.com/news/local/asian-american-virginians-continue-to-face-barriers-in-accessing-vaccines-heres-what-advocates-say-would/article_9ab59d77-b156-5017-a5b8-531129312c3d.html.

2019

Wangui Muigai, “‘Something Wasn’t Clean’: Black Midwifery, Birth, and Postwar Medical Education in All My Babies,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 93, no. 1 (2019): 82-113, doi: 10.1353/bhm.2019.0003.

2019

“Native American Nurse History,” Nurses You Should Know, retrieved from https://medium.com/nurses-you-should-know/nativeamericannursehistory/home.

2020

Ayah Nuriddin, Graham Mooney, and Alexandre I. R. White, “The Art of Medicine: Reckoning with Histories of Medical Racism and Violence in the USA,” Lancet 396, no. 10256 (2020): 949-951, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32032-8.

2017

Ayah Nuriddin, “The Black Politics of Eugenics,” Nursing Clio (2017), https://nursingclio.org/2017/06/01/the-black-politics-of-eugenics/.

2019

Dierdre Cooper Owens and Sharla M. Fett, “Black Maternal and Infant Health: Historical Legacies of Slavery,” American Journal of Public Health 101, no. 10 (2019): 1342-1345, doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305243.

1997

Martin S. Pernick, “Eugenics and Public Health in American History,” American Journal of Public Health 87, no. 11 (1997), 1767-1772, doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.11.1767.

2017

Lisa Provence, “Former Vice Mayor, Activist Holly Edwards Dies,” C-Ville Weekly (January 9, 2017), https://www.c-ville.com/former-vice-mayor-activist-holly-edwards-dies/.

2021

Meredith Reifschneider, “Those of Little Note: Enslaved Plantation ‘Sick Nurses,’” Nursing History Review 29 (2021): 179-201, doi:10.1891/1062-8061.29.179.

2008

Susan M. Reverby, “‘Special Treatment’: BiDil, Tuskegee, and the Logic of Racism,” Journal of Law and Medical Ethics 36, no. 3 (2008): 478-484, doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.294.x.

2012

Susan M. Reverby, “Ethical Failures and History Lessons: The U.S. Public Health Service Research Studies in Tuskegee and Guatemala,” Public Health Review 34 no. 13 (2012): 1-18, doi: 10.1007/BF03391665.

2021

Susan M. Reverby, “The Mask of Unequal Health and Excess Death: A Reality,” American Journal of Public Health 111, no. 2 (2021): 89-90, doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306388.

2005

Nayan Shah, “Between ‘Oriental Depravity’ and ‘Natural Degenerates’: Spatial Borderlands and the Making of Ordinary Americans,” American Quarterly (2005): 703-725, DOI:10.1353/aq.2005.0053.

Karin Skeen and Barbra Mann Wall, Nursing and Eugenics in the early 20th Century United States, Nursing Outlook 71 (2023): 102018, DOI: 10.1016/j.outlook.2023.102018.

2023 - July 29th

2016

Brianna Theobald, “Nurse, Mother, Midwife–Susie Walking Bear Yellowtail and the Struggle for Crow Women’s Reproductive Autonomy,” Montana: The Magazine of Western History 66, no. 3 (2016): 17-35, retrieved from https://www.niwrc.org/resources/journal-article/nurse-mother-midwife-susie-walking-bear-yellowtail-and-struggle-crow.

2019

Stephen B. Thomas and Erica Casper, “The Burdens of Race and History on Black People’s Health 400 Years After Jamestown,” American Journal of Public Health 109 (2019): 1346-1347, doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305290.

2012

Charissa J. Threat, “‘The Hands That Might Save Them’: Gender, Race and the Politics of Nursing in the United States during the Second World War,” Gender & History 24, no. 2 (2012): 456-474, doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0424.2012.01691.x.

2019

Victoria Tucker, “Race and Place in Virginia: The Case of Nursing,” Nursing History Review 28 (2019): 143-157, doi: 10.1891/1062-8061.28.143.

2020

Darshali A. Vyas, Leo G. Eisenstein, and David S. Jones, “Hidden in Plain Sight – Reconsidering the Use of Race Correction in Clinical Algorithms,” New England Journal of Medicine 383, no. 9 (2020): 874-882, doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2004740.

2018

Ellen Walsh, “‘Called to Nurse’: Nursing, Race, and Americanization in Early 20th-Century Puerto Rico,” Nursing History Review 26, no. 1 (2018): 138-171, doi: 10.1891/1062-8061.26.138.

2020

Kaveh Waddell, “Medical Algorithms Have a Race Problem,” The Root (2020), https://www.theroot.com/medical-algorithms-have-a-race-problem-1845081459.

2020

Mark Zuckerman, “Reflections on Charlottesville,” The Century Foundation (2017), https://tcf.org/content/report/reflections-on-charlottesville/?session=1.

2019

Reynaldo Capucao, Jr., “Filipino Nurses and the United States at Hampton Roads, Virginia: The Importance of Place," Nursing History Review 28 (2019): 158-169, doi: 10.1891/1062-8061.28.158.

2021

Emily K. Abel, Limited Choices: Mable Jones, a Black Children’s Nurse in a Northern White Household (University of Virginia Press, 2021).

2006

Warwick Anderson, Colonial Pathologies: American Tropical Medicine, Race, and Hygiene in the Philippines (Duke University Press, 2006).

2021

Jenifer L. Barclay, The Mark of Slavery: Disability, Race, and Gender in Antebellum America (University of Illinois Press, 2021).

2021

Douglas C. Baynton, Defectives in the Land: Disability and Immigration in the Age of Eugenics (University of Chicago Press, 2020).

2012

Edwin Black, War Against the Weak: Eugenics and America’s Campaign to Create a Master Race (Dialog Press, 2012).

Lundy Braun, Breathing Race into the Machine: The Surprising Career of the Spirometer from Planation to Genetics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014).

2014

2001

W. Michael Byrd and Linda A. Clayton, An American Health Dilemma: Race, Medicine, and Health Care in the United States 1900-2000 (Routeledge, 2001).

1999

Mary Elizabeth Carnegie, The Path We Tread: Blacks in Nursing Worldwide, 1854-1994, 3rd ed. (Jones & Bartlett Learning, 1999).

2021

Elizabeth Catte, Pure America: Eugenics and the Making of Modern Virginia (Belt Publishing, 2021).

2003

Catherine Ceniza Choy, Empire of Care: Nursing and Migration in Filipino American History (Duke University Press, 2003).

2008

Gregory Michael Dorr, Segregation's Science: Eugenics and Society in Virginia (University of Virginia Press, 2008)

2002

Sharla M. Fett, Working Cures: Healing, Health, and Power on Southern Slave Plantations (University of North Carolina Press, 2002).

1998

Gertrude Jacinta Fraser, African American Midwifery in the South: Dialogues of Birth, Race, and Memory (Harvard University Press, 1998).

1995

Vanessa Northington Gamble, Making a Place for Ourselves: The Black Hospital Movement, 1920-194 (Oxford University Press, 1995).

1996

David Barry Gaspar and Darlene Clark Hine, eds., More Than Chattel: Black Women and Slavery in the Americas (Indiana University Press, 1996).

2005

Sheba Mariam George, When Women Come First: Gender and Class in Transnational Migration (University of California Press, 2005).

2015

Tanya Hart, Race, Poverty, and the Negotiation of Women’s Health in New York City, 1915 – 1930 (New York University Press, 2015).

1993

Darlene Clark Hine, “From Hospital to College: Black Nurse Leaders and the Rise of Collegiate Nursing Schools,” in Professional and White-Collar Employments, Nancy F. Cott, ed. (De Gruyter, 1993).

1989

Darlene Clark Hine, Black Women in White: Racial Conflict and Cooperation in the Nursing Profession, 1890-1950 (Indiana University Press, 1989).

2012

Beatrix Hoffman, Health Care for Some: Rights and Rationing in the United States since 1930 (University of Chicago Press, 2012).

2017

Rana A. Hogarth, Medicalizing Blackness: Making Racial Difference in the Atlantic World, 1780-1840 (University of North Carolina Press, 2017).

2014

Jonathan Kahn, Race in a Bottle: The Story of BiDil and Racialized Medicine in a Post-Genomic Age (Columbia University Press, 2014).

2011

Firoozeh Kashani-Sabet, Conceiving Citizens: Women and the Politics of Motherhood in Iran (Oxford University Press, 2011).

2014

Jean J. Kim, "Professionalizing 'Local Girls': Nursing and U.S. Colonial Rule in Hawai'i, 1920-1948," in Precarious Prescriptions Contested Histories of Race and Health in North America, Laurie B. Green, John Mckiernan-Gonzalez, and Martin Summers, eds. (University of Minnesota Press, 2014).

2020

Sonja M. Kim, Imperatives of Care: Women and Medicine in Colonial Korea (University of Hawaii Press, 2020).

2005

Wendy Kline, Building a Better Race: Gender, Sexuality, and Eugenics from the Turn of the Century to the Baby Boom (University of California Press, 2005).

2019

Jim Kristofic, Medicine Women: The Story of the First Native American Nursing School (University of New Mexico Press, 2019).

2011

Paul A. Lombardo, ed. A Century of Eugenics in America: From the Indian Experiment to the Human Genome Era (Indiana University Press, 2011).

2018

Jenny M. Luke, Delivered by Midwives: African American Midwifery in the Twentieth-Century South (University Press of Mississippi, 2018).

2005

Howard Markel, When Germs Travel: Six Major Epidemics That Have Invaded America and the Fears they Have Unleashed (Vintage, 2005).

2012

John Mckiernan-Gonzalez, Fevered Measures: Public Health and Race at the Texas-Mexico Border, 1848-1942 (Duke University Press, 2012).

2006

Natalia Molina, Fit to Be Citizens: Public Health and Race in Los Angeles, 1879-1939 (University of California Press, 2006).

2013

Kim E. Nielsen, A Disability History of the United States (Beacon Press, 2013).

2003

Nancy Ordover, American Eugenics (University of Minnesota Press, 2003).

2018

Deirdre Cooper Owens, Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology (University of Georgia Press, 2018).

2016

Phoebe Ann Pollitt, African American and Cherokee Nurses in Appalachia: A History, 1900-1965 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2016).

2015

Sujani K. Reddy, Nursing and Empire: Gendered Labor and Migration from India to the United States (University of North Carolina Press, 2015).

2012

Dorothy Roberts, Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-create Race in the Twenty-first Century (The New Press, 2012).

1998

Dorothy Roberts, Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty (Vintage, 1998).

2020

Joy Sales, “‘Revolutionary Care’ as Activism: Filipina Nurses and Care workers in Chicago, 1965-2016,” in Our Voices, Our Histories: Asian Pacific Islander Women, Shirley Hune and Gail M. Nomura, eds. (New York University Press, 2020).

2005

Mary Seacole, Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands (Penguin, 2005).

2006

Todd L. Savitt, Race and Medicine in Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century America (Kent State University Press, 2006).

2001

Nayan Shah, Contagious Divides: Epidemics and Race in San Francisco’s Chinatown (University of California Press, 2001).

2005

Susan L. Smith, Japanese American Midwives: Culture, Community, and Health Politics, 1880-1950 (University of Illinois Press, 2005).

2009

Debra Anne Susie, In the Way of Our Grandmothers: A Cultural View of Twentieth-Century Midwifery in Florida (University of Georgia Press, 2009).

2016

Robert Wald Sussman, The Myth of Race: The Troubling Persistence of Unscientific Idea (Harvard University Press, 2016).

2006

Susie King Taylor, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp: An African American Woman's Civil War Memoir (University of Georgia Press, 2006).

1929

Adah B. Thoms, Pathfinders: A History of the Progress of Colored Graduate Nurses (New York: Kay Printing House, 1929), https://catalog-hathitrust-org.proxy01.its.virginia.edu/Record/000019745.

2015

Charissa J. Threat, Nursing Civil Rights: Gender and Race in the Army Nurse Corps (University of Illinois Press, 2015).

2020

Arlene Marcia Tuchman, Diabetes: A History of Race and Disease (Yale University Press, 2020).

2015

Nicholas Wade, A Troublesome Inheritance: Genes, Race and Human History (Penguin Books, 2015).

2013

Keith Wailoo, Alondra Nelson, and Catherine Lee, eds., Genetics and the Unsettled Past: The Collision Between DNA, Race, and History (Rutgers University Press, 2013).

2008

Harriet A. Washington, Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present (Anchor, 2008).

2022

Christopher Willoughby, Masters of Health: Racial Science and Slavery in U.S. Medical Schools (University of North Carolina Press, 2022).

2021 - March 15th

Brian Cameron, “UVA and the History of Race: Property and Power,” UVA Today (March 15, 2021), https://news.virginia.edu/content/uva-and-history-race-property-and-power.

2017

Michael Swanberg, “A Canary in the Coal Mine: Exploring African American Women's Lived Experience of Childbirth,” PhD diss., (University of Virginia, 2017), DOI:10.18130/V3093J.

1998

James Roberts and Renae Nadine Shackelford, Urban Renewal and the End of Black Culture in Charlottesville, Virginia: An Oral History of Vinegar Hill (Jeffereson, NC: McFarland & Company, 1998).

2017 - December 1st

Jordy Yager, “A New Page: Longtime 10th and Page Residents are Seeing a Shift in the Neighborhood,” Cville (December 1, 2017).

2020

Kevan J. Klosterwill, Alissa Ujie Diamond, Barbara Brown Wilson, and Jeana Ripple, Constructing Health: Representations of Health and Housing in Charlottesville’s Urban Renewals, Journal of Architectural Education 74, no. 2 (2020): 222-236, DOI:10.1080/10464883.2020.1790932.

2010

Sarita M. Herman, “A Pedestrian Mall Born out of Urban Renewal,” Magazine of Albemarle County History 68 (2010): 78-109.

2021 - March 15th

2021 - March 8th

2021 - March 25th

2021 - March 22nd

2021 - March 18th

2020 - July 27th

2020 - January 9th

2019 - September 25th

2019 - September 4th

2019 - September 4th

2019 - September 4th

2021 - March 11th

2019

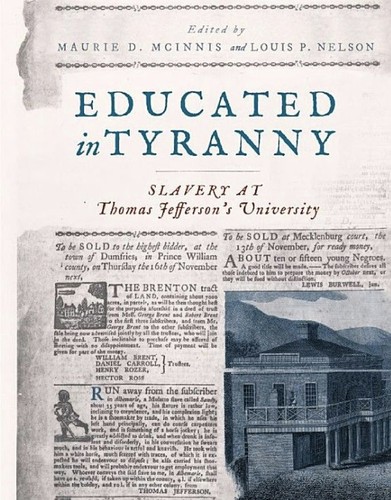

Louis P. Nelson and Maurie D. McInnis, "Landscape of Slavery," in Maurie D. McInnis and Louis P. Nelson, eds., Educated in Tyranny: Slavery at Thomas Jefferson's University (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2019)

2022

Lucille Stout Smith, Unforgettable: Jackson P. Burley High School, 1951-1967.

2022 - February 13th

Erin Edgerton, “PHOTOS: Unforgettable, story about Jackson P. Burley High School Unforgettable: Jackson P. Burley High School,” Daily Progress (13 Feb 2022).

2018

Louis P. Nelson & Claudrena Harold, eds., Charlottesville 2017: The Legacy of Race and Inequity (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2018).

A syllabus developed by three historians of medicine that illustrates that questions of race and racism should be central to studying the histories of medicine and science. The syllabus offers insight into the historical legacies of racism in medicine and health care that has contributed to America's long disparate treatment of Black people and centuries-long neglect of Black health concerns.

See: https://www.aaihs.org/syllabus-a-history-of-anti-black-racism-in-medicine/

2020 - August 12th

A History of Anti-Black Racism in Medicine Syllabus by Antoine S. Johnson, Elise A. Mitchell, and Ayah Nuriddin published by Black Perspectives

A Collaborative Research Initiative of The Carter G. Woodson Institute’s Center for the Study of Local Knowledge and the Virginia Center for Digital History

Raised/Razed dives deep into Charlottesville, VA’s oldest African American neighborhood, charting the lives of residents as they faced racially discriminatory policies and a city government that saw them as the only thing between it and progress. Learn the hard truths of the federal Urban Renewal program, and the broader history of its effect in Durham, NC and other communities across America.

Lorenzo Dickerson and Jordy Yager

Carter G. Woodson Institute for African-American and Africana Studies

Collaboration between the Philippine Nurses Association of Virginia, Virginia Humanities, and Bjoring Center for Nursing Historical Inquiry

![“[S]he Could...Spare One Ample Breast for the Profit of Her owner”: White Mothers and Enslaved Wet Nurses’ Invisible Labor in American Slave Markets,”](https://community.village.virginia.edu/loris/rhc//ms/b4/msb4asvt7lq1753nbqz6qkjwf820.jpg/full/,500/0/default.jpg)